Communication: Part 3 - Anthropological approaches to the study of Symbolism

Anthropological approaches to the study of Symbolism

The anthropological study of symbols has developed into a comprehensive field that includes (a number of) different approaches or trends. Collectively, these approaches are referred to as symbolic anthropology. Some well-known anthropologists who have contributed to the study of symbols are Geertz, Turner and Levi-Strauss. Although their approaches differ, they all investigate the meanings of symbols and symbols as a means of communication.

To introduce you to the symbolic anthropology, we will briefly discuss the approaches of Claude Levi-Strauss, Clifford Geertz and Victor Turner. In this post, I will show you how these different anthropologists have applied the seemingly simple concept of Symbolism to a complex system of thought.

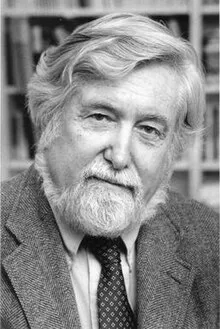

Claude Levi-Strauss

Claude Levi-Strauss, the "father" of French structuralism, regards culture as:

"a surface representation of underlying mental structures that have been affected by a groups physical and social environment as well as its history"

This means that culture is the outward picture of underlying structured thought processes found among all groups, but because different groups have different circumstances, their cultures vary. According to Levi-Strauss, all social phenomena can have a structure. What is important here is the idea that human thought processes are also structured into pairs of polar opposites, such light versus dark, good versus evil, nature versus culture, raw versus cooked, and self-interest versus common good. The most significant of these pairs is self versus the other, because according to Levi-Strauss, this contrast is necessary for true symbolic communication to occur, and culture depends on this type of communication. Levi-Strauss reckoned that people use their creative, intellectual skills to manipulate symbols, which enable them to deal with realities and contrasts of existence, such as life and death, and body and soul.

To illustrate Levi-Strauss's idea of the contrast between nature and culture and people's manipulation of symbols in order to deal with realities and contrasts of existence, let's consider the world of human habitation and the "wilderness" with reference to the Lele of Central Africa. The Lele are cultivators who live in villages situated in clearings in the forest. The forest is an important source of food and other plant materials needed for various purposes. Also, apart from obtaining meat, the hunt in the forest is a sacred and a prestigious activity, giving the forest a sacred character. Men are the hunters and go into the forest regularly, but women go there less often and on certain occasions, they are forbidden to enter the forest until certain rituals have been performed. The ultimate significance of the forest is vested in the idea that it is the abode of spirits, which are linked to water and animals in the forest. These spirits apparently control the fertility of women and help men hunt well. This connection also influences what women may eat. Fish, for instance, is forbidden, as they are linked to the forest spirits and are dangerous to women.

In the example of the Lele, it is possible to detect a series of structural associations and contrasts. On the one hand, there is a connection between men, the forest and spirits; on the other hand, there are women and their activities in the village and clearings.

Levi-Strauss's work on religion, especially myth and ritual, is situated in the sphere of ideas related to the manipulation of symbols to deal with the realities of existence. According to him, myths have a logic and structure, the analysis of which informs us about the human mind and how it operates. Levi-Strauss was concerned with myth as a type of thought, and also as an example of the working out of the universal structural principles which underlie all human cultural and social systems. The contradictions and oppositions (life vs death, nature vs culture, maternal vs paternal) are expressed and processed in mythology. Levi-Strauss sees myth as a form of sacred language; it tells a story. Myths have symbolic meanings and are sacred to the group in which the myth is told.

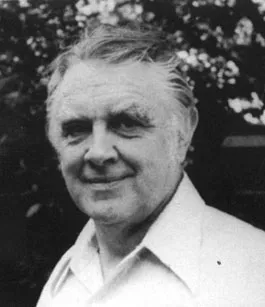

Clifford Geertz

Some scholars approach the study of culture from the point of view that cultures are systems of shared meanings and systems of symbols. Foremost among these is the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz. According to Geertz, the symbolic systems of culture provide models of reality and models of behaviour that enable people to carry out social actions. Anthropologists should study observable events to determine their meaning. Events such as sheep raids, cockfights, mass festivals and priest consecrating ceremonies symbolically express various themes in social life, and both reveal to and teach the participants something about themselves. In order to understand the behaviour patterns of people of other societies, the anthropologist interprets social action as a "text" that he/she "reads". Geertz calls the method he uses "thick descriptions". A single activity may have various "layers" of meaning that convey different messages. In describing an event, the anthropologist's first step is to try to ascertain what it means to the participants. For instance, in describing a wink, the anthropologist might call this action a "conspiratorial wink" rather than "a contraction of the eyelid". The second step is to try to discover overall themes in events and to determine what they demonstrate about the culture itself.

To illustrate Geertz's views, we briefly describe his analysis of Balinese cockfights. These are important social events and are subject to an elaborate system of rules, originating many generations ago. Geertz sees cockfights as the embodiment of many themes in the Balinese world-view. Cocks are symbols of masculinity with which the owners identify. Furthermore, because of their mindless ferocity when fighting, the cocks symbolise the crude animality that is strongly discouraged by Balinese custom. For example, the Balinese keep their emotions under strict control and babies are not allowed to crawl, since they regard this as too animal-like. Thus the cockfight is associated with ambivalent feelings of satisfaction and disgust. It is watched in complete silence. Although heavy bets are laid on the roosters, the owners feel that, symbolically, there is more at stake than money. What is at stake is the temporary loss or gain of social status. Yet nothing really happens to anyone but the roosters. Money losses and gains tend to even out, since cockfights are frequent and roosters are evenly matched by convention. No one's status really changes and people only humiliate each other symbolically.

Geertz believes that the cockfight brings together a number of themes, such as masculinity, animal savagery, status, blood sacrifice, rivalry, pride, loss and chance, and presents them in an ordered, structured way. It is events such as these that reveal the emotions upon which the social hierarchy is based.

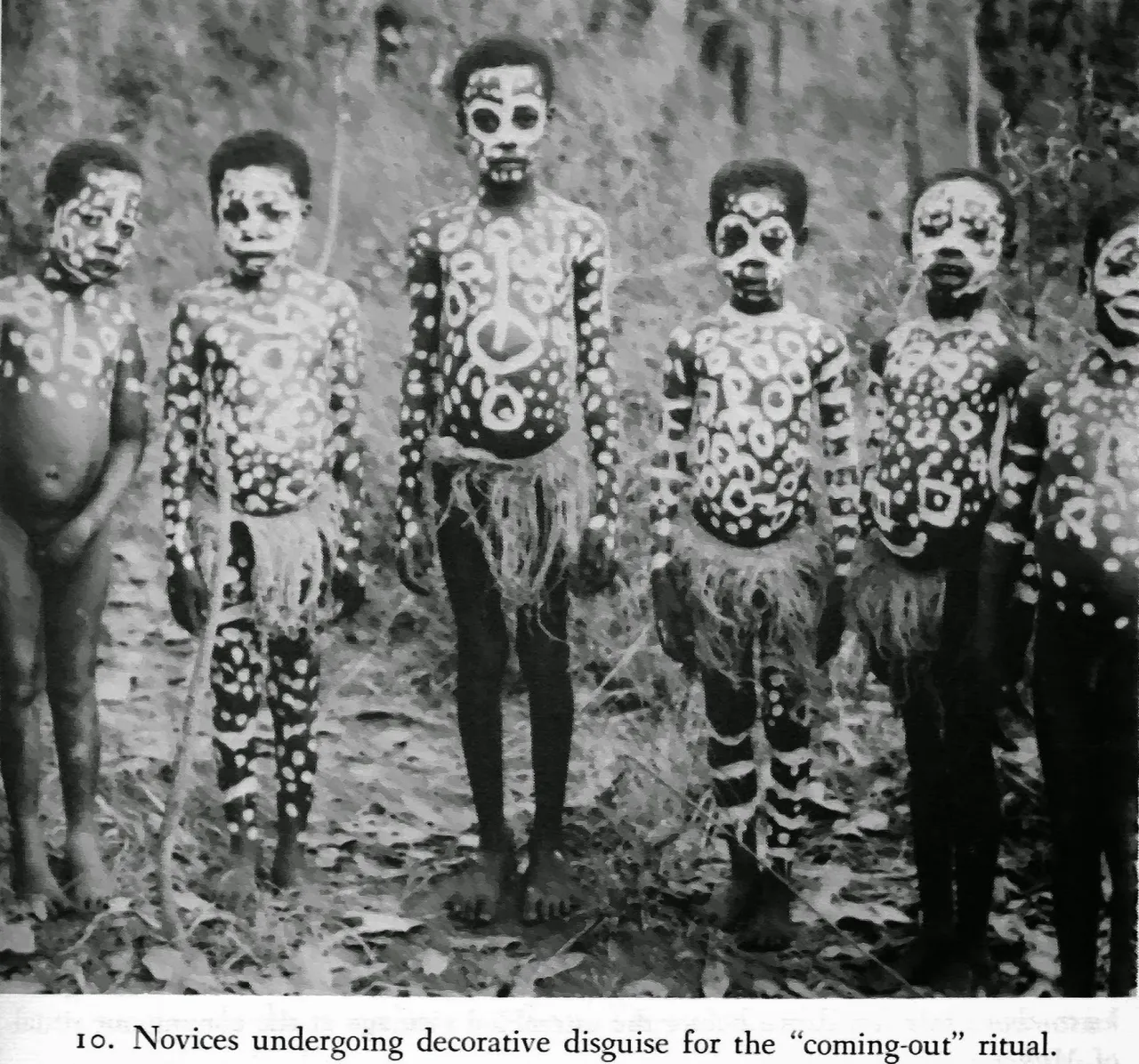

Victor Turner

Victor Turner's approach focuses on the relations between symbols, the world and experience, in other words, on the link between symbols and natural and emotional meanings. Turner is concerned with ritual symbols (rituals are social actions linked with people's belief in the supernatural) and he regards them as part of the social process (the way of life of a group of people). He believes that the meaning of a symbol is only partly expressed in any one ritual. To understand its full significance, it is necessary to study the entire system of rituals of which that ritual is a part. In his work on Ndembu rituals (the Ndembu live in Zambia), Turner notes that each ritual has what he calls a "senior" or "dominant" symbol. The mudyi tree explained below is an example of a dominant symbol.

Turner identifies the following three properties of Ndembu ritual symbols:

Condensation: This means that many things and actions are brought together in a single symbol, in other words, a single symbol has many meanings.

Disparate significata: The sources of meaning (which Turner calls "disparate significata") of a symbol are not random, but are interconnected because they possess analogous qualities or are associated in fact or in thought.

Poles of meaning: An important property of Ndembu dominant symbols is that they possess two distinct poles of meaning. At the one pole are the cluster of referents regarding the normal and social order of society, the principles upon which the social structure is based, the norms and values inherent in relationships, and types of groups. At the other pole the cluster of referents are usually natural and physiological phenomena. Turner calls the first pole the "ideological" pole and the second pole the "sensory" pole. The meaning content of the referents at the sensory pole is closely related to the outward form of the symbol.

Ndembu have a term for "symbol" and this term means "a blaze or landmark, something that connects the unknown with the known". For them, therefore, symbols point towards or reveal other things. Through symbols, basic elements in Ndembu society and culture are made visible and accessible to public action. Included in the symbols are social and cultural associations and they refer to natural and physiological facts found in everyday experience. Each symbol has a wide range of meanings, which in some respects share a common, underlying theme. An example is the mukula tree, which the Nbembu use as a symbol with regards to, for instance, matrilineal descent (descent according to the mother's bloodline), hunting, menstrual blood, and the meat of animals. The underlying theme is that the mukula tree secretes a sticky red gum, which clots or solidifies quickly and is compared by the Ndembu to blood. It is used in, among other contexts, the boys' initiation ceremonies. As soon as circumcision has been performed and the wounds are still bleeding, they are placed on a mukula log. The idea is that the circumcision wounds should heal quickly in accordance with rapid solidifying of red gum. In this context of male initiation, the red gum also represents masculinity and the life of an adult male, who will inevitably shed blood as a hunter and a warrior.

Another example is the mudyi tree, or milk-tree, which is the focal symbol of the Ndembu girl's puberty ritual. According to Turner, at its ideological pole, the tree represents womanhood, motherhood, the motherchild bond, a novice undergoing initiation into mature womanhood, a specific matrilineage, the process of learning "women wisdom", the unity and perdurance of Ndembu society, and all of the values and virtues inherent in the various relationships domestic, legal and political controlled by matrilineal descent. Each of these aspects of its (ideological) meaning becomes paramount in a specific episode of the puberty ritual; together they form a condensed statement of the structural and communal importance of femaleness in the Ndembu culture. At the sensory pole, the same symbol stands for breast milk (the tree exudes milky latex; the significata associated with the sensory pole often have a more or less direct connection with some sensorially perceptible attribute of the symbol), mother's breast, and the bodily slenderness and mental pliancy of the novice (a young slender sapling of mudyi tree is used).

In the next part we will go into the understanding of Symbolism using the above three anthropologists approaches.

End of Part 3

Thank you for reading.

Images are linked to their sources in their description and references are stated below.

Authors and Text Titles

FS Miller 1979:Introduction to cultural anthropology

VW Turner 1967: The forest of symbols:aspects of Ndembu ritual

Seymour-Smith 1986: Macmillan dictionary of anthropology

Haviland 2002: Cultural anthropology

C Geertz 1973: Interpretation of Culture

C Levi-Strauss 1977: Structural Anthropology vol 2

JJ Honigman 1976: The development of anthropological ideas

S Nanda & PL Warms 2004:Cultural Anthropology