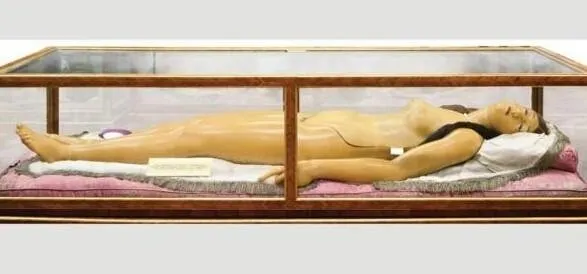

Nightmares in waxA tiny foetus, its foot kicking out of a womb; an intestine piled up next to a lifeless figure, her torso ripped open from the string of pearls on her neck to her abdomen. Our natural reaction is to recoil with disgust, to dismiss these eerie waxworks as freak show objects. Yet to do so is to misunderstand them, says the author of a new book. “They do say something different to us today from what they meant at the time,” says Joanna Ebenstein, co-founder of the Morbid Anatomy Museum in New York. Her book The Anatomical Venus reveals how a figure that provokes an uneasy reaction in viewers now was once a popular tool for instruction. This Anatomical Venus, produced by the workshop at La Specola in Florence between 1784 and 1788, is displayed in her original rosewood and Venetian glass case at the Josephinum, Vienna, Austria. (Credit: Josephinum, Collections and History of Medicine, MedUni Vienna/Photo Joanna Ebenstein)Nightmares in waxA tiny foetus, its foot kicking out of a womb; an intestine piled up next to a lifeless figure, her torso ripped open from the string of pearls on her neck to her abdomen. Our natural reaction is to recoil with disgust, to dismiss these eerie waxworks as freak show objects. Yet to do so is to misunderstand them, says the author of a new book. “They do say something different to us today from what they meant at the time,” says Joanna Ebenstein, co-founder of the Morbid Anatomy Museum in New York. Her book The Anatomical Venus reveals how a figure that provokes an uneasy reaction in viewers now was once a popular tool for instruction. This Anatomical Venus, produced by the workshop at La Specola in Florence between 1784 and 1788, is displayed in her original rosewood and Venetian glass case at the Josephinum, Vienna, Austria. (Credit: Josephinum, Collections and History of Medicine, MedUni Vienna/Photo Joanna).

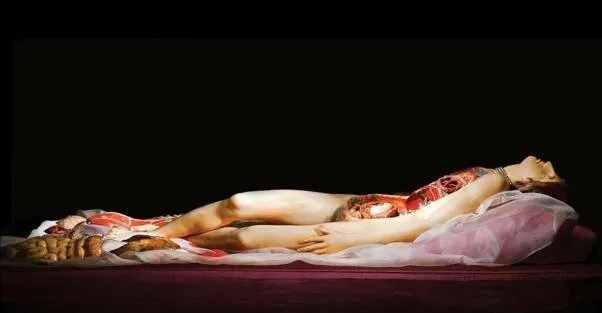

Fairground attractionIt’s a world away from Madame Tussauds. No grinning faces to be photographed in selfies; no celebrity glamour or statesmanlike poses. These are waxworks that both intrigue and repulse: models that seem to hover somewhere between freak show and operating theatre. Ebenstein aims to place them in their cultural context, looking at the history of the anatomical Venus and finding out where it fits in the 21st Century. “Since their creation in late-18th-Century Florence, these wax women have seduced, intrigued, and instructed. In the 21st Century, they also confound, flickering on the edges of medicine and myth, votive and vernacular, fetish and fine art,” she writes in her opening chapter. “How can we understand today an object that is at once a seductive representation of ideal female beauty and an explicit demonstration of the inner workings of the body? How can we make sense of an artefact that was once equally at home in the fairground and the medical museum?” This life-size 40-piece anatomical Venus is from Pierre Spitzner’s 19th-Century collection. (Credit: Université de Montpellier anatomical collection/Photo Marc Dantan/Courtesy of Thames & Hudson Ltd)

Cultural curiosityEbenstein had to wrestle with her own feelings when she first encountered the Venus. “It’s so confusing, and it has such power when you see it, it’s hard not to be drawn in,” she tells BBC Culture. “I was trying to figure out how to make sense of it – it looks so bizarre to us now. Of all the forms an anatomical teaching tool could take, how come it was that one?” She overcame her initial reaction by reading about the Venus and looking at figures in different settings. “I went to other kinds of museums and churches to try and understand the context of the culture that created it, which made me start thinking about it in a very different way from most people in the medical museum world,” she says. “My background is intellectual history, so when I look at an object that looks strange to us today, my first thought is ‘Why? Did it look strange to people at the time? What does it say about us that it now looks strange?’” (Credit: Josephinum, Collections and History of Medicine, MedUni Vienna/Photo Joanna Ebenstein)

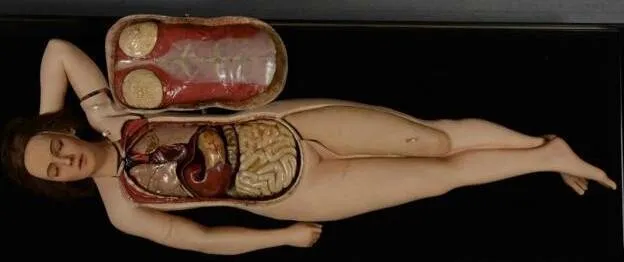

Venus in pearlsEbenstein realised that the Venus was not an oddity: it was truly a product of its time. Leopold II founded La Specola after becoming the Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1765; he aimed to educate Florentines in the empirical observation of natural laws and challenge the more irrational practices of the Roman Catholic church. His new museum, Ebenstein argues, “would make available to the general public the rare and valuable cultural artefacts previously secreted in the Medici Wunderkammern, or cabinets of wonder”. In a period when the study of the natural world included what we know today as science, aesthetics and metaphysics, she claims, “the Medici Venus was a perfect embodiment of the Enlightenment values of her time, in which human anatomy was understood as a reflection of the world and the pinnacle of divine knowledge, and in which to know the human body was to know the mind of God.” Venerina (Little Venus), is a 1782 life-size dissectible wax model created by the workshop of Clemente Susini at La Specola for Museo di Palazzo Poggi, Bologna, Italy. (Credit: Museo di Palazzo Poggi, Universita’ di Bologna. Photo Joanna Ebenstein)

Dissecting beautyIn a bid to depict humans in a more realistic way, visual artists of the Renaissance carried out their own dissections – more even than anatomists of the era. According to Ebenstein, Leonardo da Vinci “is said to have dissected more than 100 bodies, and famously ‘sketched cadavers he had dissected with his own hand’”. One key anatomical text of 1543, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), was illustrated with woodcuts “thought to be by Titian’s studio in Venice”. That overlap of disciplines was the background for the anatomical Venus. “One of the things that makes the Venus so hard for us to understand is that we’ve now divided up all those things in ways that wasn’t divided in the time that it was made,” Ebenstein tells BBC Culture. “We have this division between art and science, and between religion and medicine, that didn’t exist at that time.” (Credit: Josephinum, Collections and History of Medicine, MedUni Vienna/Photo Joanna Ebenstein)

One foot in the graveThe creators of the ‘Slashed Beauties’ aimed to bring anatomy out of the graveyard. “Most of anatomical knowledge was derived from dead bodies, and that’s not appropriate for a popular audience,” says Ebenstein. “So how do you create an object that can take something from the grave and the cadavers it took to make it, but make people forget that, or not know it, and make them seduced by it? A lot of her beauty has to do with that, it’s essential to making her a popular object.” There is a quote in the book from the 18th Century anatomical illustrator Arnaud-Éloi Gautier D’Agoty: “For men to be instructed, they must be seduced by aesthetics, but how can anyone render the image of death agreeable?” The waxworks harnessed aesthetics to reach a larger audience. “The popular part is really important, and I think that part really baffles people,” says Ebenstein. “They assume the Venus was made for doctors – but it wasn’t, and in that way it wasn’t made for an audience of men the way some feminists expect it to be – it was made for men, women and children, that’s really essential to understanding it.” This 1746 mezzotint of a fashionably coiffed anatomised woman, L’Ange Anatomique (The Flayed Angel), was created by Arnaud-Éloi’s father Jacques-Fabien Gautier d’Agoty. (Credit: Wellcome Library, London)

Sleeping beautyHowever uncanny they might seem to us, the wax figures were primarily teaching tools. According to Ebenstein, “Each pristine wax model at the museum was the product of the careful study of cadavers that were delivered from the nearby Santa Maria Nuova hospital.” They remain close to life. “Over 200 years after their creation, La Specola’s waxworks are still considered remarkably accurate, some of them demonstrating anatomical structures that had yet to be named or described at the time of their making.” Yet in making them more attractive than a cadaver, the waxwork sculptors were also creating art works. As Ebenstein argues, the anatomical Venus evoked “a long history of paintings and sculptures of placid, idealised nudes”. And that’s where the human detail that unnerves us came in. “She is designed to charm in every detail: her glistening glass eyes are rimmed with real eye-lashes, her bared throat is bound by a string of pearls, and she boasts a lustrous cascade of human hair.” This figure is known as ‘the Sleeping Beauty’: a 1925 replica of the original piece from 1767, it’s a breathing wax model by Swiss physician and master wax sculptor Philippe Curtius. (Credit: Madame Tussauds Archives, London. Photo Joanna Ebenstein)  >quote

>quote