Prague

Images of Prague have been passing through my memory the last few days as I finished up Franz Kafka's book, The Castle. As always when reading Kafka, the mind strains to understand, to reach the meaning in the strange characters and conversations of this enigmatic, sad, lonely, sick man.

Prague Castle at night

Often I imagined him walking through the streets of Prague, as he must have every day, and I struggled to reconcile my colorful, happy memories with images of him, which always seem to come to my mind in black and white. Perhaps because photographs in his time were black and white. Perhaps because the white of his pale consumptive skin contrasted so sharply with his dark Jewish eyes and hair and the deep shadows of his face. Perhaps because his stories, and particularly The Castle, are so cold and drab and wintery.

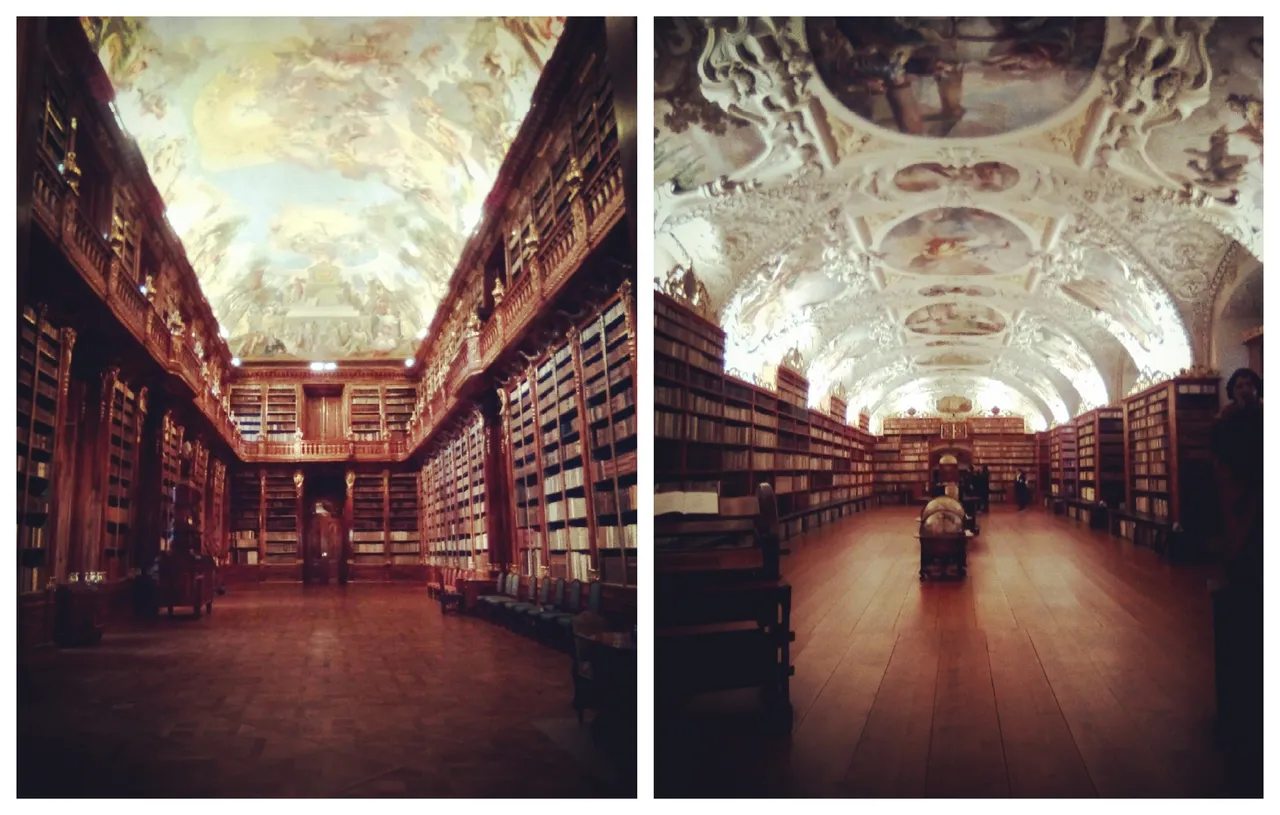

Strahov Monastery

But this was his home, the place where he spent most of his short life, when he wasn't trying his luck to get better at some sanatorium or visiting his girlfriend in Berlin. Kafka was a son of this city. Like me, he had an office job, and his stories overflow with the frustrations of senseless and endless bureaucracy. Here he lived with his parents and sisters, his strained relationship with his unreasonable father perhaps inspiring his themes of punishment for default guilt and unknown and unknowable crimes.

The interior of the Strahov Library, Prague

When I first read and tried to understand Kafka, I thought that perhaps the harsh judgement and punishment from unknowable and inapproachable authorities were a reference to God or religion. It surprised me to learn therefore when I read his biography, that the Kafkas were not religious. At one point in his life, Kafka came into contact with Hassidic (traditional) Jews, and was impressed by their devotion but horrified by their poverty.

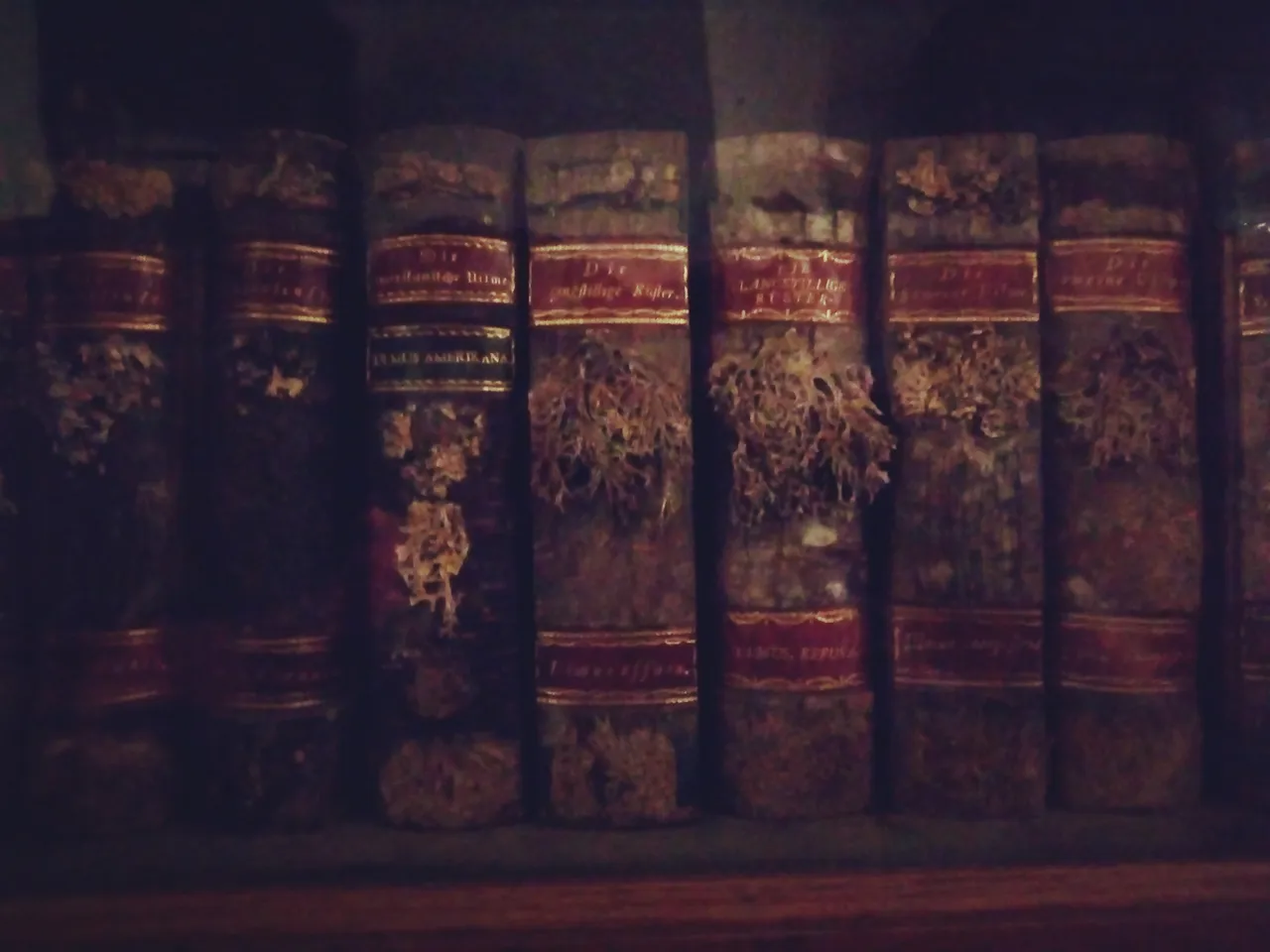

Botanical book-boxes at the Strahov library, featuring bark and lichen covers

Kafka was part of the Zionist movement, a political and philosophical ideology that sought to reverse the idea of the physical weakness of the Jewish race, which was prevalent at the time due to the popularity of eugenics (a major factor in the ideas of Nazism which would later claim the lives of Kafka's two sisters at Auschwitz). Nevertheless, his stories often bespeak the horror of illness and the weakness of the human body.

The Spanish synagogue in Prague

The greatest mystery for me in Kafka's stories is his enigmatic main character, known simply as "K." K. is hard to figure out. Though you feel pity for him, he can come across as self-seeking, unethical, even harsh and cruel. You never quite know whether to take his side. Certainly K. is based on Kafka himself, but was this an accurate expression of his own character? Or was it the way his father saw him, and the way he therefore came to see himself?

The Vltava River, Prague

Those who knew Kafka say that he was kind. He worked at an insurance company and really fought for the rights of the clients he was responsible for. He also used to laugh uproariously when he read his stories to his friends. Was it all just a fantastic joke to him? Is it nothing but satire? Is he laughing at us now, from the grave, as we pick through his writing, searching for deeper meaning? Or was it the cathartic cry of a continually broken heart?

A sculpture in the streets of Prague

Maybe we will never know. I still have one of Kafka's works left to read, his novel Amerika, and it's rumored that some of his elderly relatives have unpublished manuscripts of his locked away in a vault in Israel--maybe we'll get to read those someday too. But I kind of doubt whether reading more will lift the veil of mystery. The meaning seems always to be just one step out of reach.

Café Cerna Madona, Prague

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The photographs in this article were taken by me during a trip to Prague last December