Hello world,

The following is what I’ve learned while exploring the license templates provided by default on GitHub. I am not a lawyer of any kind and this is intended as a general guide to help map the primary differences, accompanied with some historical context, but everyone should always read the license that they pick for their own project in full. Just like we all read every EULA…. Right? ;)

For Starters

Copyright is the most common and globally recognized form of intellectual property protection that currently exists. It’s precise rules have been an on going evolution since the 1700’s with the British Statute of Anne. Originally intended as a response to the low price market of mass printed publications introduced since the invention of the printing press and other novel complications that arose as a result. Today all member nations of the World Trade Organization automatically comply with the agreed rules in what’s today known as the TRIPS Agreement as of 1995[1]. Meaning your legal claim to a copyright can be upheld in all WTO nations. By default all published works from these nations are most often automatically copyrighted.

Some quick definitions before proceeding; copyleft, free software, and open-source software.

Copyleft generally preserves the open nature of down stream works derived from the original copyleft licensed material. Meaning if I use material that’s issued using a copyleft license I then cannot copyright or limit my work any more than the original already was. In a paper published in 2005 titled Share and Share Alike: Understanding and Enforcing Open Source and Free Software Licenses[2], the author explains “that neither the Free Software Definition nor the Open Source Definition requires a license to be either a copyleft license or to be GPL-compatible in order to qualify as a free software or open source license, respectively.”

As defined by the Free Software Foundation(FSF)[3], or GNU’s four essential freedoms[4], the terms “free software” and “open source software”, defined by the Open Source Initiative(OSI)[5], are not mutually exclusive to each other, and neither term inherently fall under the copyleft classification. There is a lively debate, to put it very mildly, about the merits between the nuances of free software compared to open source. Because “the vast majority of Free Software and Open Source licenses satisfy both definitions…”[2], for the purposes here I will be using open source ubiquitously and not specifically in reference to the OSI.

The First Copyleft

Copyleft licensing, as the mirror opposite to copyright, Wikipedia tells me was first referenced back in 1976, the year the United States passed the copy right act. “COPYLEFT ALL WRONGS RESERVED”[6], which stands in stark contrast to copyright’s common phrase “ALL RIGHTS RESERVED”. However the first legally recognized copyleft license did not start appearing until the 1980’s.

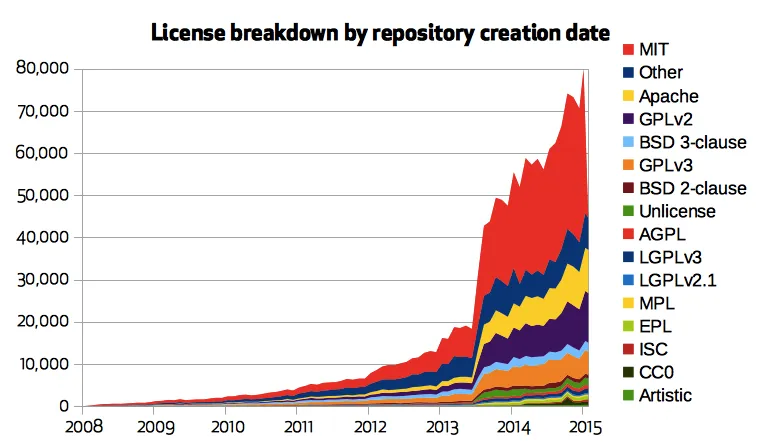

Of the 13 license templates GitHub provides, five of those are various versions of the GPL with the v1’s origins beginning in the early 1980’s. From a book titled Free as in Freedom (2.0): Richard Stallman and the Free Software Revolution, by Sam Williams[7], a series of events is detailed that give a full account of how GPLv1 emerged. In short it was as a result of the consequences of the “weaknesses of the Emacs Commune and the informal trust system that had allowed problematic offshoots to emerge. … The Emacs Commune applied only to the code of the original Emacs program written by Stallman himself. Even if it had been legally enforced, it would not have applied to separately developed imitations such as Gosmacs.”[7] Because the Emacs Commune honor system was just that, based on trust, and it did not protect the downstream derivations from again becoming copyrighted. As a result the GPLv1 was released in 1989. Version 2 was released in 1991 and v3 in 2007. GitHub’s 2015 report showed approximately 24% of repositories used one of the GPL licenses[20].

I cannot mention GPLv3 without also mentioning the tensions created as result. Today Linus Torvalds has kept the latest Linux kernel specifically licensed under GPLv2 only and not newer. Arguments on behalf of both sides for doing this, going back to the FSF vs OSI debate, are extensive. Mostly surrounding the issue of how the license interacts with other software or hardware of a proprietary nature. I leave any reading on that up to the listeners. For the purposes of keeping this concise know that GPLv2 is less compatible with some licenses than GPLv3.

Permissive Licenses

The following three licenses are not 100% copyleft but are permissive. Meaning that they exist mostly in the public domain but with only some rights reserved.

First up is the MIT license which has, as I found, a somewhat cloudy origin as reported in an article titled The mysterious history of the MIT License. While the GPL license was evolving at MIT through the 80’s, so was the MIT license. As a permissive license it was trying to give a license to software that needed to be shared without too much of a problem. As demonstrated when frustrations emerged around distributing the X Window System "under [a] license became enough of a pain that I argued we should just give it away.", quoted from Jim Gettys. However just as Stallman discovered on the same campus at around the same time, the public domain was not the best place to leave your software in the jurisdiction for a variety of reasons. It could be argued, as the author of the article, states that the first versions of the MIT license could be traced as early as 1985, more solidly in 1987 as the license for the X11 Window System, and finally the modern MIT license in 98-99. The original article by Gordon Haff is a great short read as further reading[8]. As of 2015, reported on GitHub’s blog, the MIT license holds the vast majority of repositories on the platform, at 44%[20]. I would guess this is largely because it is the most permissive license on the platform without placing the work completely in the public domain.

Next up is the BSD license, or Berkeley Software Distribution license, with a 4-clause versioformalized by the end of the 80’s, and could be considered the Berkeley campus’ permissive license counterpart to the MIT license. Eventually issues were raised around clause 3 of the 4, which stated that “All advertising materials mentioning features or use of this software must display the following acknowledgment: This product includes software developed by the…” blank, insert organization x here. Quite rapidly, as more and more organizations or individuals build on each others code, any advertisement would be mostly acknowledgements. As a result in 1999 a 3-clause & 2-clause version of the BSD license were released[9]. Both of which are included in GitHub’s default templates, together holding about 5% of GitHub’s repositories. So far we’re already almost at 75% of total repositories in 2015[20].

Last of this group of permissive licenses is the Apache License from the Apache Software Foundation of LAMP stack fame. Originally the license used for their software in 1995 was a version of the BSD 4-clause license[10]. When the the switch was made to the 3-clause BSD license Apache released version 1.1 in 2000 which retained some of the attribution requirements scratched from clause 3 of the 4-clause license, but exclusively for the purposes of documentation and not for advertising. In 2004 Apache License 2.0 was released, superseding 1.1, that completely broke off from its BSD origins and is definitely a more involved read. In 2015 the APL licensed ~11% of GitHub’s repositories.

In order of least to most restrictive, generally speaking, of these permissive licenses it goes MIT, 2 then 3-clause BSD, and Apache 2.0. Not to say restrictions are bad, but each individual or team should look into each license and choose which one suites their case best.

Weak Copyleft

Still a permissive license but considered a weak copyleft license is the Mozilla Public License, which the Mozilla Foundation currently uses. MPL 2.0 is also GPL compatible. Its origins come from Mitchell Baker who, while working for Netscape, was involved with the Netscape Public License, under which their browser was published, and also developed the Mozilla Public License v1. From her blog on January 3rd, 2012, announcing the release of MPLv2, “The MPL was created as part of the launch of the Mozilla project in 1998, and was updated once in 1999… The MPL 1.1 versions had one expert who had been involved in every word and every decision… The MPL 2.0… has 5 peers now, instead of just one.”[11]

The Eclipse Public License is the second weak copyleft license included in GitHub’s license template list. As summarized on OSS Watch the EPL “explicitly grants patent rights where necessary to operate the software, keeps the covered code itself open source, [&] allows expansion of the code via new modules that can be licensed in non-open ways.” In that report on the EPL, by Rowan Wilson[12], it’s story starts in 1999 as IBM’s IPL, then became the CPL in 2001 to make it easier for others to reuse the license. Finally becoming the EPL with the formation of the Eclipse Foundation as a result of the more than 50 organizations using the CPL.

Creative Commons

Almost to the end of the list, Creative Commons was founded as a non-profit organization in 2001 and then began publishing its first legal licenses in 2002. Wired published an article in 2011, by Duncan Geere, that gives a full history of how the organization came about[13]. It’s philosophy, “We stand on the shoulders of giants by revisiting, reusing, and transforming the ideas and works of our peers and predecessors.”[14] In the first 5 years after its release more than 90million works had been licensed under CC. Today, in the footer of Wikipedia you can find the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-A-like License(CC BY-SA). Today hundreds of millions of works are published using some form of a CC license. Ranging from copyleft forms all the way to the public domain, which is the default form of CC offered on GitHub as CC-0.

“Copyleft is a strategy of utilizing copyright law to pursue the policy goal of fostering and encouraging the equal and inalienable right to copy, share, modify and improve creative works of authorship”[16]. The two most noteable copyleft licenses are the GPL & CC BY-SA licenses.

An honorable mention that cannot be ignored is the involvement of Aaron Swartz in the open access movement and for his promotion of the freedom of information philosophy. A good part of the documentary dedicated to his life, The Internet’s Own Boy[15], which is of course published under creative commons, talks about how he helped build the code base behind the creative commons platform as a teenager, before his involvement in the creation of Reddit, and activist participation during the SOPA and PIPA bills.

Unlicense

Last on the list of licenses provided by GitHub is the Unlicense, equivalent to the public domain. Essentially releasing the work into the wild with no rights reserved. In his blog post, Set Your Code Free, from January 1, 2010, Arto Bendiken, on what I learned is not only NYD but also Public Domain Day, released all of his code into the public domain via the unlicense. His blog wrote “when you include a license statement in your software project, you are effectively making a threat to the users of your software. You are saying that if they don’t behave according to whatever arbitrary criteria you’ve set out in your license statement, you will send some men with guns after them… Now, I don’t know about you, but the least effective way to secure my cooperation is to threaten me.”[17] The rest of the blog post is also a very interesting follow up read for listeners and later that month also gave a more detailed breakdown of the unlicense[18][19].

In closing, this has been a very general overview of these licenses and their history. These are only a few to choose from with many more listed on opensource.org. OSS Watch also has a good list of reports on the history of these licenses. I hope this has helped new developers to begin selecting which license may suite them the best or maybe just provided some cool new history as to how the free and open-source landscape has evolved.

References

1. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/intel2_e.htm

2. https://lawcat.berkeley.edu/record/1119855?ln=en

3. https://www.fsf.org/about/what-is-free-software

4. http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html

5. https://opensource.org/osd

6. http://www.jk-quantized.com/experiments/8080Emulator/TinyBASIC-2.0.pdf

7. https://static.fsf.org/nosvn/faif-2.0.pdf

8. https://opensource.com/article/19/4/history-mit-license

9. ftp://ftp.cs.berkeley.edu/pub/4bsd/README.Impt.License.Change

10. http://oss-watch.ac.uk/resources/apache2

11. https://blog.lizardwrangler.com/2012/01/03/mozilla-public-license-version-2-0-released/

12. http://oss-watch.ac.uk/resources/epl

13. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/history-of-creative-commons

14. https://creativecommons.org/2002/10/16/creativecommonsannounced-2/

15. https://archive.org/details/TheInternetsOwnBoyTheStoryOfAaronSwartz

16. https://copyleft.org

17. https://ar.to/2010/01/set-your-code-free

18. https://ar.to/2010/01/dissecting-the-unlicense

19. https://unlicense.org/

20. https://github.blog/2015-03-09-open-source-license-usage-on-github-com/

21. https://isc.tamu.edu/~lewing/linux/

All original content is published using CC4.0 BY-SA