The marbled crayfish, or marmorkreb, didn't exist as a species 25 years ago. Today, they number in the countless millions, and are seriously threatening ecosystems in Europe and Madagascar.

The marbled crayfish. [Image source]

25 years seems an astonishing time for a whole new species to appear, but it all occurred thanks to a single mutation. A slough crayfish, a native of Florida and Georgia, apparently developed a mutation while being shipped to Germany. It gained the ability to reproduce without sex- it cloned itself. Marbled crayfish are universally female, all genetically identical, and each is born with the ability to reproduce itself over and over again. It only takes a single marbled crayfish to start a new invasive population, and they've spread to Europe, Madagaskar, and Japan, largely through being released from home aquariums.

Marbled crayfish aren't unique in the animal kingdom for their ability to clone themselves. This process is known as parthenogenesis, and is found in a few other plants and animals. It's known in invertebrates, fish, amphibians, reptiles, and even birds (including domesticated chickens and turkeys!). For hopefully obvious reasons, parthenogenesis always occurs among females. It's somewhat unusual to have an entirely parthenogenic species, however- it's usually just a last ditch strategy if there aren't any available males for mating. Other entirely parthenogenic species include a type of velvet worm and a couple species of goblin spiders.

A parthenogenetic Komodo Dragon hatchling. Komodo dragons can reproduce either sexually or parthenogenetically. [Image source]

The marbled crayfish is an incredible success story as an invasive species, and they raise a lot of interesting questions. First off, why doesn't every species reproduce this way? It clearly is quite effective. It also, however, leaves the species quite vulnerable in some ways. Most notably, any species that is entirely composed of clones is far more vulnerable to disease. Any disease deadly to one is deadly to all. When a species is more genetically diverse, it's more likely to have members that are resistant or even immune to a disease. A single nasty pathogen could wipe out the entire species.

Next, why don't we see more of these species alive today or in the fossil record? Well, it's likely that clonal species are particularly short lived. The disease vulnerability is an obvious reason why, but there's another more subtle one- since all the members of the species are genetically identical, evolution is inhibited in the population. Without sex to mix up genetics, the species can't effectively respond to changing circumstances in their environments like a non clonal species. To confuse things even more, many species are morphologically identical to the degree that clones are but are extremely genetically diverse- so it's nearly impossible to tell if a fossil species is cloned, even if we find significant numbers of examples of them, which is highly unlikely among a clonal species with a probable species lifespan measured in tens of thousands of years or less.

The European range of the marbled crayfish. They're also present in Madagascar and Japan. [Image source]

Interestingly, thought marbled crayfish are all genetically identical, there is a reasonably large variation in coloring. This is most likely the result of environmental influences. Marbled crayfish raised alone in captivity tend to often be blue rather than grey. Even more interestingly, phenotypal variation in clones is pretty common, even in artificially produced clones. This is because your appearance, or phenotype, isn't exactly determined by your genes- instead, the way those genes are expressed are influenced by the way the environment affects them.

The marbled crayfish, and other clonal species, are a strong part of the argument that speciation- the formation of new species- might be a much more rapid process than previously thought. Speciation occuring over a single generation, like with the marbled crayfish, might be significantly more common than we once expected.

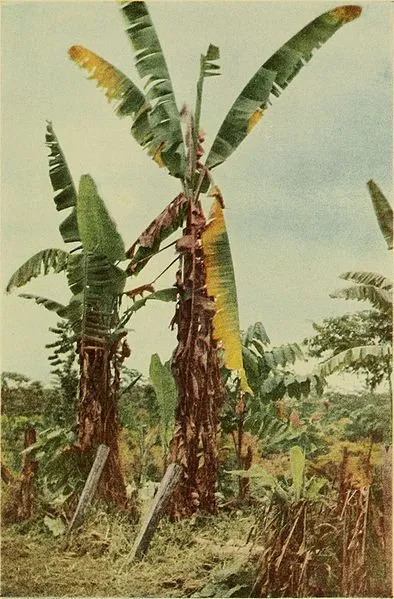

One reason this is all especially important to humans is that many of our important crops are clones. One of the most notable is bananas- which are not only the most widely consumed fruit in America, but are actually a critical staple food source for millions of people around the globe. While there are other varieties of banana, the overwhelming majority are a variety known as Cavendishes, which are all clones of one another. They're facing a potential extinction threat from the same fungus that wiped out the last popular variety of banana, the Gros Michel or Big Mike- which, by all accounts, was much bigger and tastier than the Cavendish. (The slapstick trip on a banana peel gag was actually a real threat in the early 1900s in America, since bananas were even more absurdly popular then.) If the Cavendish goes, people around the wold face economic dissolution and even starvation.

A Big Mike banana plant in 1919 suffering from the wilting disease that killed them all off by the 1950s. [Image source]

Bibliography:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/05/science/mutant-crayfish-clones-europe.html

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-018-0467-9

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marbled_crayfish

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-43032061

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gros_Michel_banana

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parthenogenesis

My geology classes