Men read the Book of Job and think they are watching a courtroom drama. They see it as the ultimate debate on why good people suffer. They analyze the arguments of Job's friends, trying to figure out which theological points are right or wrong. They are playing the ego's favorite game, intellectual debate, and they are as blind as Job's friends were.

The Book of Job is not a theological dissertation on suffering. It is a divine and terrifying vivisection of the human ego, specifically its most subtle and dangerous form: the pious, righteous ego.

1. Job is the Pious Ego

Job is not a humble servant of God. Job is a "blameless and upright" man whose entire identity is wrapped up in his own righteousness. His goodness is his most prized possession. He is the archetypal "good man" who secretly believes that his performance has put God in his debt. He is the ego at its most refined, a whitewashed tomb of impeccable behavior. This is precisely why he is the perfect subject for this spiritual surgery. The "Accuser" (Satan) is not just an external being; he is the voice of the eternal question that plagues all piety: "Does Job fear God for nothing?" Does he serve God, or does he serve his own self-image as a good man?

2. The Friends are the Religious Ego

Job's friends, Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar, are not just bad counselors. They are the embodiment of dead, systematic religion. They are the Pharisees of the wilderness. They come with a neat, tidy, theological formula: Suffering is the result of sin. They have God figured out, trapped in their intellectual system. They cannot see reality; they can only see their doctrine. They are not there to comfort; they are there to be right. They represent the intellectual ego trying to solve a spiritual mystery with a textbook.

3. Job's Speeches are the Ego Defending Itself

When suffering comes, Job does not surrender in silent faith. His true nature is revealed. He does not grieve his losses; he defends his reputation. His long, agonizing speeches are not the cries of a suffering man; they are the legal arguments of a plaintiff demanding a day in court with God. "I desire to argue my case with God." (Job 13:3). He is consumed with proving his innocence. His suffering is secondary to his wounded pride. The pious ego, when its transactional relationship with God is violated, does not turn to God; it tries to sue Him.

4. God's Answer is the Annihilation of the Ego

The climax of the book is when God finally speaks from the whirlwind. And this is the part everyone misunderstands. God does not answer a single one of Job's questions. He does not explain the "bet" with Satan. He does not justify His actions. He does not engage in the debate at all.

To do so would be to validate the ego's premise that it has the right to an explanation. Instead, God performs a divine demolition. He reveals a reality so vast, so powerful, so alien, and so utterly beyond the ego's tiny frame of reference that Job's entire case evaporates into absurdity. "Where were you when I laid the earth's foundation?" He doesn't give Job an answer; He obliterates the questioner.

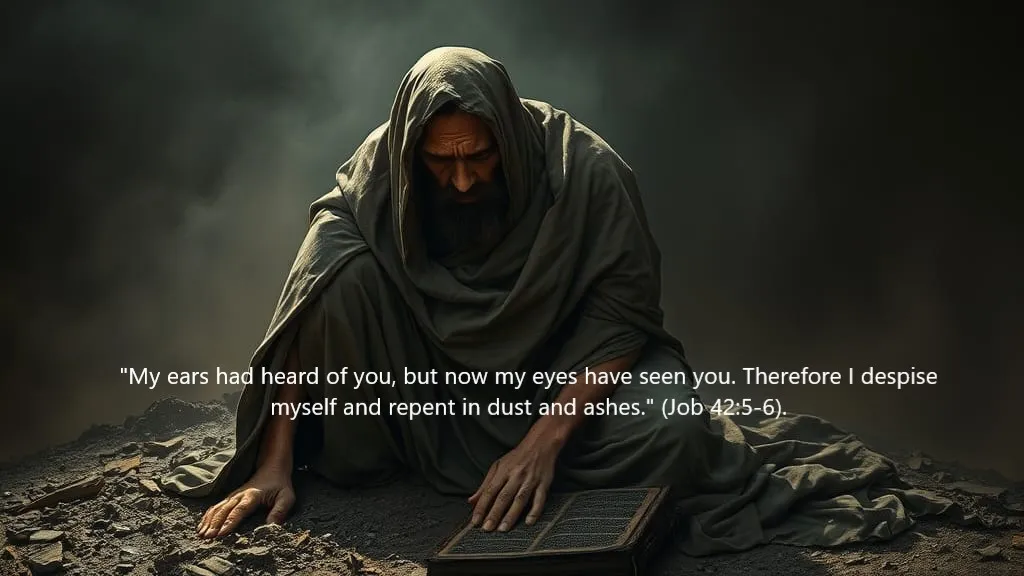

5. The Final Repentance is Ego-Death

Job's final words are the key to the entire book. "My ears had heard of you, but now my eyes have seen you. Therefore I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes." (Job 42:5-6).

This is not Job admitting to a secret sin. He is repenting of his self. He is despising the "I" that thought it was righteous, the "I" that dared to argue with God, the "I" that built its identity on its own goodness. It is the moment of total ego-death. He moves from "hearing" second-hand, conceptual, religious knowledge to "seeing," which is direct, unmediated knowing.

Job is not a book about suffering. It is a book about seeing. It demonstrates that you can be the most righteous man on earth by the ego's standards and still be completely blind. And the only cure for that blindness is for the "you" who thinks you are righteous to be utterly and completely annihilated.