In 1917, the United States went to war. The government built up public support for America's participation in "the Great War" by promoting patriotism, such as through the now-iconic image of Uncle Sam.

Though the character was originally created around the early

nineteenth century, Uncle Sam didn't become a prominent symbol

until WWI. Source: Public domain, Library of Congress.

This promotion of American patriotism, against a backdrop of 23 million immigrants entering the country, provoked a desire for non-immigrants to protect their definition of American identity. This largely translated into anti-immigrant sentiment and public support for tighter immigration laws.

One such popular law was a literacy test. One had been introduced periodically since 1894, but was subsequently vetoed by the respective president in office. In 1917, the literacy test was introduced again, with enough support to override President Wilson's veto. Now, immigrants wishing to enter the United States would have to read 30-40 words of their native language. Additionally, due to xenophobic fears like "yellow peril," the Immigration Act of 1917 set up the Asiatic Barred Zone, which denied all immigrants from southeast Asia and parts of the Middle East.

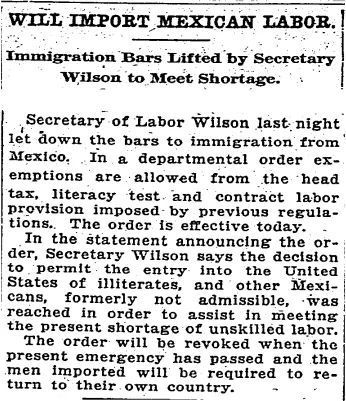

In June 1918, however, this law was put on hold. Increased demand for supplies during the war, as well as increased demand on bodies to comprise the army, put a drain on workers for farms, coal mines, and railroad repair. To alleviate this drain, Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson lifted the literacy test for Mexican immigrants intending to work in those areas.

The Washington Post, June 20, 1918

Initially, this allowance was meant to be temporary; Mexican workers, already likely receiving minimal pay, would have a small amount of money withheld, which would then be returned when the worker returned to Mexico. By August, this provision was also lifted. This exemption from the literacy test for Mexican workers lasted until 1921.

In modern discourse, one common argument for restricting immigration is the accusation that immigrants will "steal" non-immigrants' jobs. At the same time, immigration supporters and activists will often lift up the accomplishments of immigrants as proof that they bring value to American culture. Support for a merit-based immigration system continues to grow. In all of these contexts, immigrants are reduced to their abilities and their potential for productivity.

However, this approach to immigration ignores all the qualities in a person beyond their ability to work. While it's great to celebrate one's accomplishments, that should not be a person's sole qualifications to enter the country or to otherwise have a good life. This approach ignores immigrants' worries, their hopes, their interests. For Mexicans entering the United States in 1918, it ignores their fear and need to escape the violent Mexican Revolution, which had been raging for nearly a decade at the time. For current immigrants, judging entry based on skills or abilities ignores how America represents a better life. Jealously protecting “American” identities undercuts the dream that we can all thrive — and what could be more patriotic than encouraging people to come and follow their American dreams?

Source:

Don M Coerver, "Immigration/Emigration," in Mexico: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Culture and History, ABC-CLIO, 2004.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.