The Power of Ads

This weekend is the superbowl! The yearly sporting event represents a lot of great things for different people: a fun rivalry, time with friends, the halftime show, great snack food... and ads. Many viewers tune in for the creative and ambitious commercials aired during the tournament, rather than the sport itself. These commercials often act as a litmus test for the country at a given point; last year, Budweiser drew controversy after airing a pro-immigration commercial during the superbowl a month into the Trump presidency.

In this spirit, I decided to see what I could learn about the United States in 1918 through its ads. I bought a copy of today's Philadelphia Inquirer to see how it compares with an issue of the same newspaper from January 29, 1918.

What do ads say about the newspaper industry?

My first observation is how much larger and more plentiful ads are in today's issue. Vendors bought quarter, half, and even full page ads, and each folded section had a full-page ad on its last page. This contrasts with the 1918 issue, which has fewer and smaller ads.

This shows one of the largest ads in the 1918 newspaper, advertising Lit Brothers,

which was one of the main department stores in the city at that time.

Ultimately, newspaper ads serve to make money for the newspaper, and this disparity of ads indicates a changed attitude towards newspapers. In 1918, this was the primary way to learn about current events, so the newspaper business thrived. After the rising popularity of television in the 1950s, TV news became more common and newspaper sales began to decline. Since the 2000s, online news and the 24-hour news cycle have made newspapers even more obsolete. The increased size and amount of ads likely indicates one of many ways the Philadelphia Inquirer has attempted to raise funds to maintain its print edition; additionally, the newspaper has began putting its online articles behind a paywall.

Location, location, location

Many ads in each issue mention the vendor's location. However, in today's issue, the majority of ads list several cities, indicating that ads are being bought by larger companies; those companies often have multiple locations; and either the Inquirer has a larger audience geographically or its audience can travel to a greater distance conveniently. Ads without addresses entirely often referred to non-profit organizations like charities, and popular brands like car models. In 1918, ads primarily listed street addresses, especially within Center City -- without mentioning the city they're in. This implied that readers did not want to, or couldn't easily, travel far to purchase goods.

That location is now a Burlington Coat Factory.

It's useless to compare the subject matter of the ads, because a large enough percentage of today's ads reference commodities that simply didn't exist or weren't common in 1918, like cars, air conditioners, or TVs. However, it is interesting to compare the style and approach of both sets of ads.

How much are people willing to read?

Today's ads are colorful, with large fonts, snappy slogans, and enticing pictures. One home improvement service promises me, "Give us ONE DAY and we'll give you a NEW BATH!" A smaller notice asking readers to donate their car to Wheels For Wishes includes a seemingly unconnected photo of a small child hugging a puppy. Not much information is given -- readers are frequently redirected to phone numbers and websites -- likely due to shrinking attention spans and competing sources of attention.

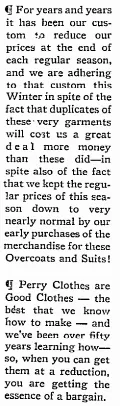

(The text on the right is an excerpt of an ad for Perry & Co., at 16th and Chestnut.)

The ads in 1918 have significantly more text. Ads advocate for the products they're displaying, giving articulated reasons why readers should buy them. Not only does this indicate readers having more time and willingness to read ads, but it also suggests a heightened need to trust the products being bought. With the proliferation of explanations in ads, consumers must want the best quality products and be willing to search around for them; meanwhile, today, a culture of convenience means that consumers don't necessarily want to spend time researching what they should buy and why.

Is that all we can learn from ads?

Naturally, one can only learn so much browsing the newspaper and focusing on advertisements. If one were really interested, a scholar could do a deeper dive into each business or industry mentioned, research their institutional histories or level of popularity, and make inferences from there. In the meantime, however, a quick study of newspaper ads reveals quite a bit on attitudes towards consumerism, news, and the surrounding city.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.