One of the biggest problems that has confronted geology over the years is the dolomite problem. Dolomite is a sedimentary rock of remarkably similar composition to calcite, the mineral that makes up limestone- but rather than being calcium carbonate, it's calcium magnesium carbonate. In rock form, dolomite is also occasionally known as dolostone, but only as dolomite when referring to it in mineral form. It's far from the most exciting mineral on the planet, but it's possibly the most challenging- largely because we don't really understand how it forms.

The Dolomite Mountains of Italy. The mountains are named after the mineral, which is named after 18th century minerologist Deodat Dolomieu. [Image source]

The reason we don't understand how it forms? It's because it simply doesn't form today in appreciable amounts. There are massive deposits of it that formed in the past- the Dolomite mountains in Italy, for instance, get their name from the huge amounts of dolostone present in them. Today, however, it's only found forming in anaerobic, super-saline lagoons in Brazil, and one time in the urinary bladder of a dog for some weird reason. It's even hard to make in a lab- most of the time when we try to make it, the components just turn into a mixture of calcium carbonate and magnesium carbonate, not dolomite. It wasn't until 1999 that we first created synthetic dolomite at low temperatures.

For the past couple of hundred years, this posed a severe issue for geologists. This is, in no small part, thanks to uniformitarianism, which I've talked about quite a few times before. Uniformitarianism is, in a nutshell, the idea that the past is the key to the present. It's still incredibly useful, and shouldn't be discounted- but it definitely went too far quite often in the past. Notably, it led to denials that catastrophic events occurred in the past or that past processes might be different than present ones. Today, thanks to the Bretz Flood and the Chicxulub impactor, that strict view of uniformitarianism has loosened its hold on geology. It's not surprising, therefore, that we've made more progress in figuring out the Dolomite Problem since the 1990s than ever before.

Dolostone dating from the Upper Triassic, found in Slovakia. [Image source]

There are two main categories of potential solutions to the Dolomite Problem. The first category of solutions states that the dolomite was originally deposited as something else, usually limestone, and then was chemically transformed into dolomite over time. The second type claims that dolomite was deposited by processes that no longer operate on large scales on Earth. (There actually is a third type of solution, one that says dolomite was deposited by comet dust. While this is possible, since carbonates are known to be found in comet tails, this is somewhat more improbable than the other two.)

There's an interesting parallel to this question in vulcanology- Ol Doinyo Lengai, the Masai Mountain of God. Ol Doinyo Lengai is a natrocarbonatite volcano- the only one, apparently, in the history of the planet. There are, however, tons of deposits from strictly carbonatite volcanoes all over the place in old rifting zones. So perhaps there were plenty of natrocarbonatite volcanoes in the past, and the sodium (where the natro- prefix comes from in natrocarbonatite) gets leached out normally over time. Or, perhaps, Ol Doinyo Lengai really is just unique. (I wrote a whole blog post on it, if you're interested.)

Ol Doinyo Lengai. [Image source]

There is a lot tempting about the idea that dolomite was chemically converted out of limestone, but there are some pretty key problems with the idea- notably, that in order for water leaching through limestone to convert it to dolomite on the huge scale it is found in deposits would be pretty astonishing. You'd expect a certain amount of veins of limestone to be left in it, which isn't the case. This is leading more and more geologists to think that dolomite production really has dropped off.

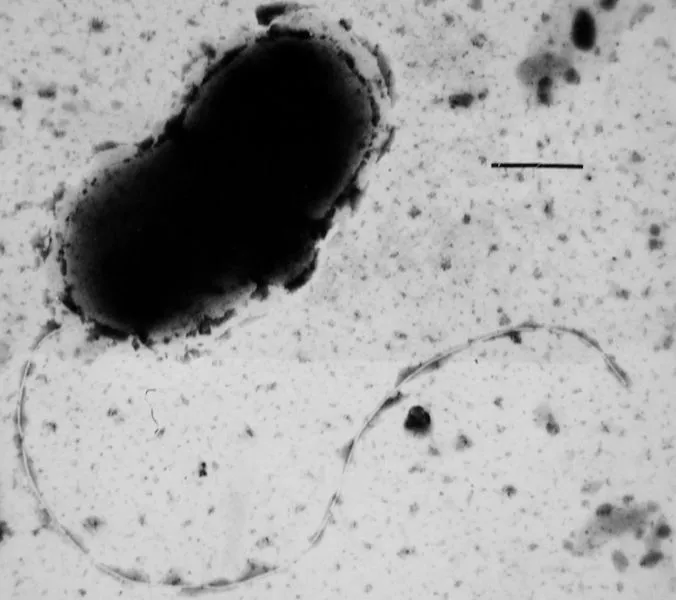

In those lagoons in Brazil I mentioned earlier, geologists may have pinpointed part of the problem. The Red Lagoon, which, well, lives up to its name, still has dolomite forming at the bottom of its murky, reddish water. The rotten egg-smelling water gains its red color from sulfate reducing bacteria, which produce hydrogen sulfide. Geologist Judith McKenzie tested their possible connection to dolomite formation by taking extracted bacteria from the Red Lagoon, then putting them into a refrigerator iin a slurry consisting of sand, nutrients, sulfate, and the ingredients for dolomite. Examining it a year later, she found dolomite crystals precipitating between the sand grains. When the sulfur reducing bacteria take in sulfates, they also absorb magnesium, calcium, and bicarbonate, use some as nutrients, then excrete the rest. In essence, the bacteria are pooping out the ingredients for dolomite in a concentrated form.

These bacteria might very well have been the source of all that dolomite, but claiming that all of those huge dolomite formations are bacteria poop is, if you'll forgive the unfortunate mixed metaphor, a bit hard to swallow. Thankfully, due to the way crystals are formed, dolomite wouldn't have to be entirely made of bacteria excreta. They would just have to give the starting seed crystals, and then inorganic processes would have continued growing the dolomite crystals in the same way. This explanation also gives us a reason why dolomite production stopped- those sulfate-reducing bacteria aren't the most tolerant of free atmospheric oxygen, and became less and less common after the rise of plants on the surface of Earth. Interestingly, the Dolomite Mountains defy that explanation. They're definitely old limestone transformed into dolomite through the addition of magnesium- though some geologists, like McKenzie, think that sulfate-reducing bacteria likely played a role there as well.

Desulfovibrio vulgaris, a sulfate-reducing bacteria. (Though not necessarily one of the bacteria that help form dolomite.) [Image source]

While we've made huge progress in figuring out the issue in the last twenty years, the problem is still far from being resolved. Apart from the sheer frustration of having an unanswered scientific question like the Dolomite Problem floating around for two centuries, there are plenty of good reasons for resolving it. Dolomite has plenty of important uses- it's often used for ornamental stone, in the production of magnesium, as flux for the smelting of iron, and in the production of glass. Most importantly to geology, however, dolomite is an important petroleum reservoir rock, so understanding it better can help oil companies better find and retrieve oil deposits. (Oil might be the devil as far as climate change is concerned, but it's still the reason geology gets a lot of its funding, for better or worse.) The course of answering the problem, however, shows how important underlying scientific mindsets and philosophies are to solving specific scientific problems.

Bibliography:

- My class notes from Sedimentology and Stratigraphy class.

- https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/msa/ammin/article-abstract/100/2-3/483/40379

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolomite

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolomitization

- http://discovermagazine.com/1996/feb/thedolomiteprobl700

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sulfate-reducing_microorganisms

- http://www.ajsonline.org/content/299/4/257.abstract

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dolomites

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ol_Doinyo_Lengai

- http://www.eu-geology.com/?page_id=107