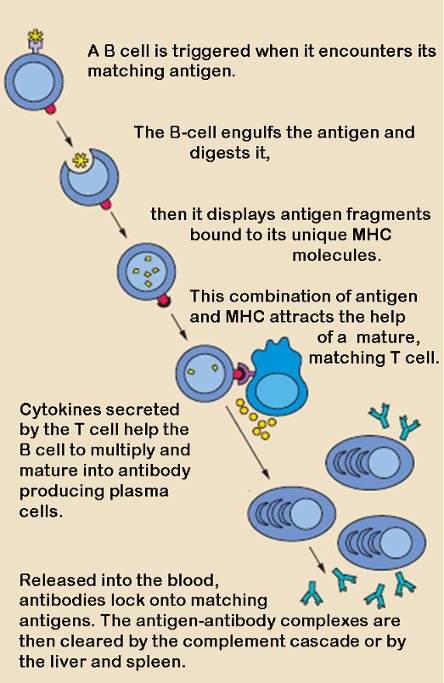

B Cell Activation in a Normal Immune System

B cells and T cells work together when a foreign body is detected. The diagram shows how these two sentinels in the immune system operate like a tag team to identify and destroy an invading organism. In lupus, both T cells and B cells are implicated in the inflammation that is so damaging. The signaling received by the cells somehow is wrong and these two act as a tag team not against an invading foreign body, but against tissues in organs--skin, liver, kidney--anywhere and everywhere.

This blog begins where every discussion of disease should begin: with a patient. The patient was only ten years old. She suffered from systemic lupus and an associated autoimmune skin disorder called lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP). Her case was reported in the January 2018 journal, Medicine. The case report describes a child in extreme distress, one whose symptoms perplexed treating physicians at Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China. It explains that the combination of SLE and LEP, in one so young, is "extremely rare".

The child had been ill with fatigue and malnourishment for a year prior to admission. Two weeks before admission she had developed painful plaques on her skin and nodules below the surface. She had fever, cough, alopecia (loss of hair, common in lupus), and oral sores. However, she didn't have double-stranded DNA antibodies, and she had a very modestly positive titer (concentration) of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) in her blood. These are two criteria on the diagnostic checklist issued by the ACR (American College of Rheumatology). Doctors felt they couldn't justify a diagnosis of SLE.

Finally, a kidney biopsy and lung scan were performed. Now there was evidence of SLE, according to the ACR checklist. Treatment with high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide began. To no avail. After a month of remission, the girl relapsed and died. Her treating physician explained the delay in administering therapy: "The diagnosis was not straightforward as the manifestations did not satisfy 4 of the 11 diagnostic criteria"

The name lupus, it is believed, came from the appearance a malar rash sometimes bestows on a lupus patient. The rash spreads across the cheeks and bridge of the nose in a very distinctive, wolf-like pattern--that's what some people say, anyway.

So what is this ACR list that holds the power of life and death over a patient? The eleven diagnostic criteria are provided by the American College of Rheumatology to guide physicians. These criteria constitute a diagnostic bible for rheumatologists who treat lupus. Generally, the criteria are applied inflexibly--as was the case with the 10-year-old child described above.

How common is it that diagnostic inflexibility (in interpreting the ACR checklist) results in withholding essential care? Pretty common, it seems, if we are to judge from statistics. The rheumatology community admits to delays in diagnosis that may last years. One source, the Lupus Foundation of America, suggests six year is the average wait time. Try to imagine the number of people who fall through the cracks in six years.

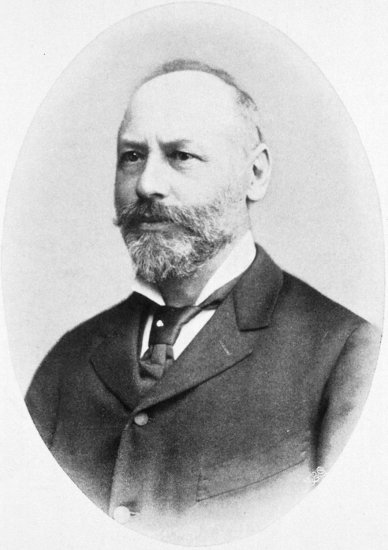

Moritz Kaposi (yes the same after whom Kaposi's sarcoma is named) was the first person to recognize and describe lupus as a systemic disease. Before his insight, lupus was viewed as dermatological disease. In 1872, Karposi explained the profound systemic effect the disease could have and cautioned that it could be fatal. This picture is in the public domain, because of its age. It was taken in 1890 (author unknown) and published in 1902 by J. F. Lehmann. The image is currently held at the National Library of Medicine.

Difficulty in diagnosing lupus is understandable, since nobody really knows how the disease comes about. Many people (I'm among them) wonder if lupus is one disease, or if it is a collection of diseases that share some serology and symptoms. New manifestations of lupus regularly surprise doctors. Research papers abound that describe "novel" and "rare" initial presentations of the disease. And those papers don't include histories of patients who got lost in the diagnostic morass, or those who may have even died of mysterious ailments that were actually lupus.

As a demonstration of how unpredictable lupus is, and how unreliable the ACR criteria are as diagnostic tools, I offer below three more case studies. Each was reported in a research journal. Taken together they throw into serious doubt the viability of the ACR's diagnostic criteria.

Image Source: Pixabay

Case #1

An article entitled, Atypical Presenting Symptoms of Acute Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with Enteritis and Cystitis was published in the February 29, 2016 Hindawi Journal. The article describes the case of a Japanese man who arrived at Kitano Hospital, Osaka, in acute distress. He had abdominal pain, severe diarrhea and bloody feces. After initial testing, he was treated for infectious enteritis. This treatment seemed to be helpful. However, symptoms soon returned after medication was discontinued.

Further exploration at the hospital revealed clinical abnormalities, among them thickening of bowel and bladder walls. Eventually, the patient also presented with pulmonary symptoms. Serology revealed elevated titers of autoantibodies. It was then that a diagnosis of SLE was considered. Very high doses of intravenous corticosteroids were adminstered. Symptom remission was achieved, but on discharge it turned out that maintenance on high-dose oral prednisone was not sufficient to suppress disease symptoms. Monthly infusions with cyclophosphamide were also necessary.

The Hindawi article ends with a caution about the danger of delayed diagnosis(!!). The author states: corticosteroids might have been adequate for the management of lupus enteritis if the case had been promptly diagnosed. Early diagnosis is of great importance for the optimal management of lupus enteritis. Of course, this prompt diagnosis was not forthcoming, because the patient at first did not satisfy four of the eleven criteria on the ACR checklist.

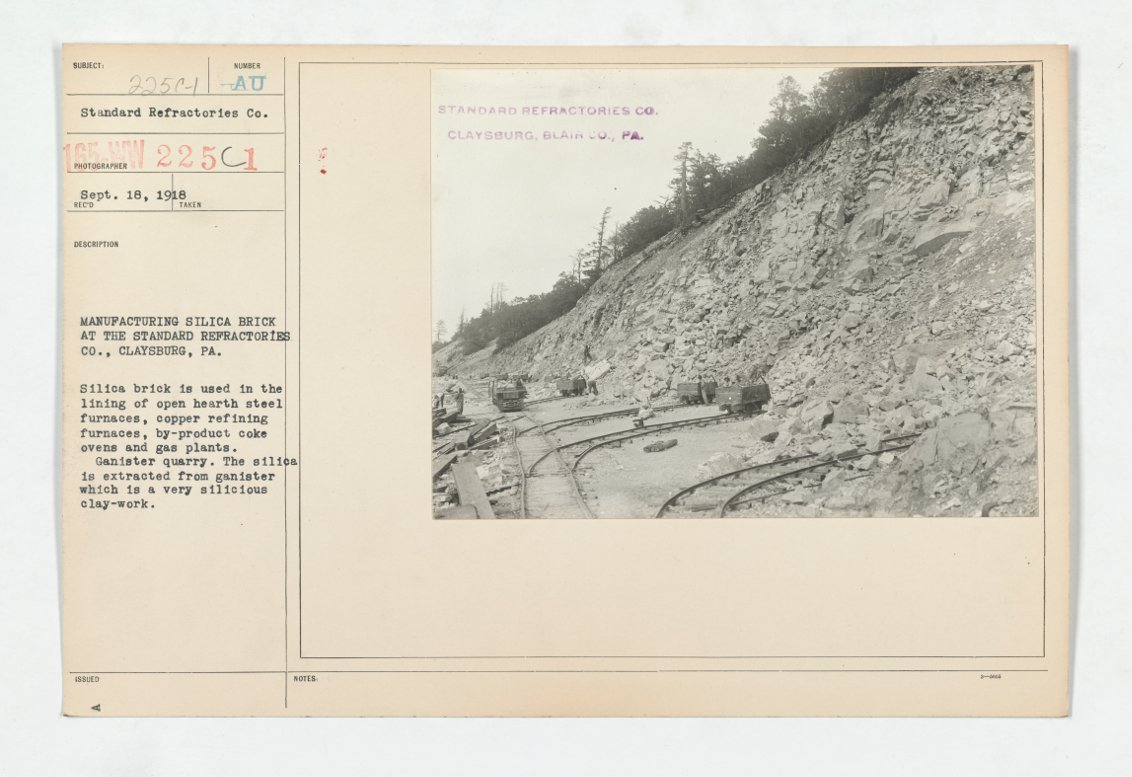

Silica Exposure Is Associated with the Development of Autoimmune Disease

A single cause for lupus has not been discovered. However, contributing factors are suspected. These include both a genetic predisposition and environmental exposure. Autoimmunity tends to run in families, and lupus, specifically, does have a familial link. One of the environmental associations that's pretty well established is silica, especially if the exposure is occupational. This picture shows silica mining in Claysburg Pennsylvania. It is attributed to the US War Department and is in the public domain.

Case #2

This case report, Guillain-Barre Syndrome as a Rare Initial Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, appeared in the April 13, 2018 Journal Neurology.

The patient was an 18-year-old woman. She had spent two weeks in a community hospital and was transferred to Oklahoma University Medical Center with a diagnosis of Guillain-Barre syndrome. Upon admission to OUMC, she was intubated (put on a respirator). Treatment for Guillain-Barre was commenced, but was not effective. Further testing revealed pleuritic involvement (her lungs were inflamed) and the presence of suggestive autoantibodies in her blood. Treatment regimen was changed as SLE was diagnosed.

Plasmapheresis and infusion with high dose corticosteroids were begun. This resulted in remission of disease activity. The authors of this article emphasize that although SLE and Guillain-Barre have been associated in the past, Guillain-Barre as a first symptom of lupus is "exceedingly rare and not well understood".

In blood tests, it's not just the presence of ANA (antinuclear antibodies) that suggests the possibility of lupus. The concentration, or titer, has to be above a certain level, for lupus to be considered. Lupus is really a general term that can be applied to three different types of disease: systemic lupus (SLE); discoid lupus (DLE); and drug-induced lupus. Image Source: Pixabay

Case #3

This one involves an 8-year-old boy with sickle cell anemia. The article appeared in the June 26, 2007 Journal of West African Medicine. The child went through several years with lupus-like symptoms before being diagnosed. He had fever, skin lesions, an enlarged liver, arthritis and seizures. The authors admit the difficulty in diagnosing lupus because of the rarity of a sickle cell/lupus overlap.

The child was given corticosteroids and anti-malarials, but not a diagnosis of SLE. However, he returned to the hospital because of relapses (seizure, fever, lesions) for the next two years. Only when he presented with oral lesions and a malar rash was he given a diagnosis of SLE.

We are not told how the child fared after his diagnosis, but it may be assumed that more aggressive treatment for lupus was offered. The authors of the article state that the overlap between cycle cell anemia and SLE is "rare". They further state that only 23 cases of this overlap have ever been reported. In this boy's case, after years of a variety of symptoms, it was the appearance of a malar rash, discoid lupus and mouth ulcers--all on the ACR checklist--that led to a diagnosis and aggressive treatment.

So what is known about SLE, besides the fact that it cannot be clearly defined, or cured? Some facts about lupus are absolutely certain. It is a disease of inflammation. It is a disease in which the immune system goes haywire and attacks healthy cells instead of foreign bodies. No one knows how this immune aberration is triggered, but it is clear that two types of cells, B cells and T cells, work in conjunction when the disease is active.

An article in the May 2018 issue of Frontiers in Immunology suggests that our innate immune system (we're born with that) and our adaptive immune system (this develops over time, through experience) both play a role in lupus pathology. The article emphasizes that if we could understand how the immune system malfunctions in lupus, the way would likely be paved "for better management, therapy, and perhaps prevention" of this very complex autoimmune syndrome.

Image source: Pixabay

In conclusion, it doesn't make sense to me, given the acknowledged complexity of lupus, and the lack of understanding about SLE, how a simple checklist can be a sensitive diagnostic tool. I believe it's time to throw the ACR checklist away. From the information and examples provided in this blog, it's clear that the list doesn't work.