Note: This is the story of Ishi, a Native American man who was the last of his tribe. If you have read the recent tribute to author Ursula LeGuin on my @donkeypong blog, this is a connected story. LeGuin’s father, Professor Alfred Kroeber at the University of California, basically adopted Ishi and made him a part of the university’s Anthropology Department, employing him as a research assistant. As I discussed in the Ursula LeGuin post, both of her parents’ work in chronicling Native American cultures, languages, and legends had an impact on the worlds LeGuin created in her fantasy and science fiction novels.

California was a sleepy backwater until 1848, when gold was discovered there. Within a few years, hundreds of thousands of new residents had arrived in the Gold Rush, putting pressure on the state’s remaining tribes of Native Americans. Gold mining in the Sierra Nevada foothills deposited sediment into many of the rivers and streams, wrecking some prime fishing areas. Agriculture spread throughout the valleys; there were many more mouths to feed as more and more miners and other settlers arrived.

Ishi's people were associated with the Yana language group, which you can see in the upper middle of this map.

State (and later federal) troops waged a war on the last remaining pockets of Native Americans, who the settlers did not understand and viewed as a security threat. Between this violence and the introduction of European diseases like smallpox, it was nothing short of an extermination. The traditional way of life, the cultures, and the languages, not to mention the people themselves, were quickly being eliminated.

In 1865, federal troops had a skirmish with a local Native American Indian tribe near Oroville, California that came to be known as the Three Knolls Massacre. They killed 40 members of the small tribe, while others who tried to escape were killed by cattle ranchers. The Yahi tribe was believed to have gone extinct as a result of this attack.

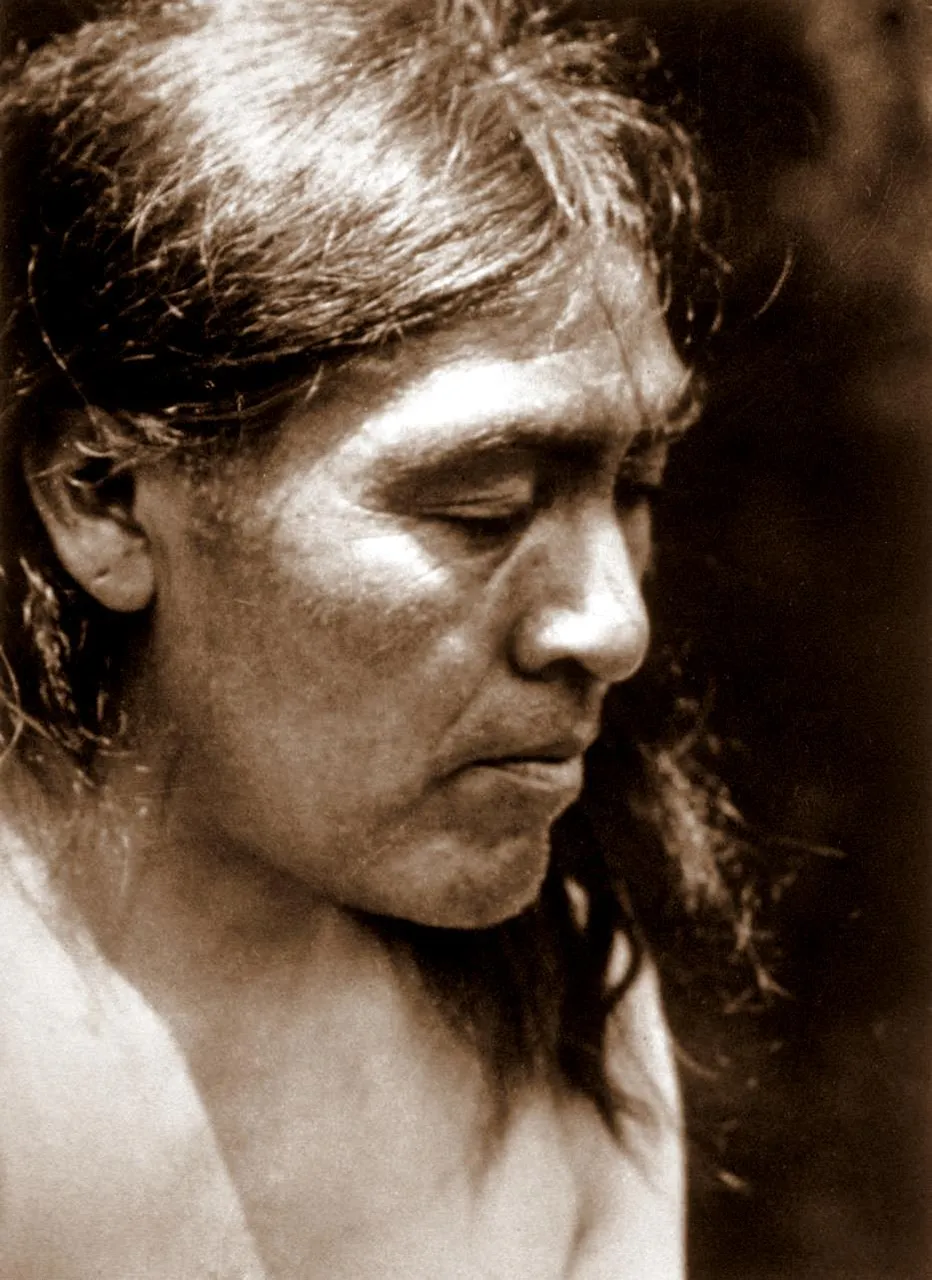

In 1911, a man named Ishi emerged from the wilderness around Mount Lassen. He was the last Yahi tribesman. Ishi and a small group had been on the run for more than 40 years. The others had died and Ishi was the last of his kind, undernourished and emaciated. Some say he was ‘the last wild Indian.’

After decades of evading modern humanity, with all of his companions dead, Ishi gave up. He walked out of the wilds and into the modern world. It must have been a dramatic transition.

Professor Alfred Kroeber at the University of California basically adopted Ishi. He became not only a research subject, but was hired as a research assistant at the University of California’s Anthropology Department. Ishi provided Kroeger with a remarkable chance to study the language and culture of this tribe, which they all realized was part of a dying world that needed to be documented.

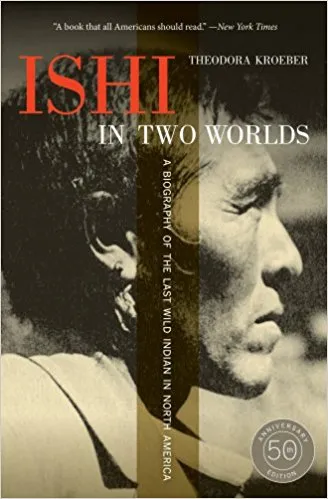

His wife, Theodora Kroeber, also possessed an advanced education in anthropology and psychology. She wrote several books about Ishi, including the definitive biography. She also penned other books about Native American legends that drew heavily upon what they learned from Ishi. Two of her books were made into movies.

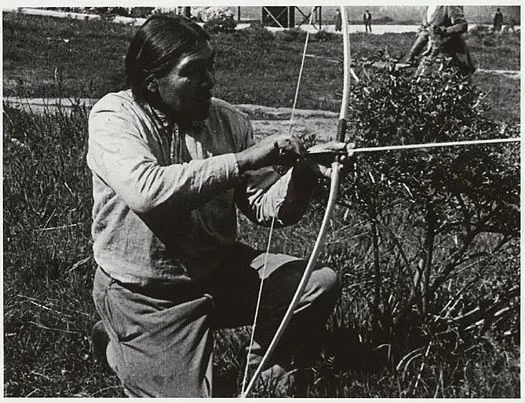

Ishi did not use his name or discuss his ancestors directly, since those things were forbidden in his tradition; Ishi meant “man” in his language. Long after Ishi’s death, an expert in Native American stone technology analyzed his arrowpoints and concluded that they were not Yahi in design. That raises the possibility that Ishi was of mixed heritage, since he may have learned how to make arrowheads from another tribe besides the Yahi.

Ishi not only provided the university’s researchers with a prime opportunity to study his culture. He also became a tour guide and something of an attraction for visitors to the university’s anthropology museum. Some have suggested that he was over-exploited in this role, though he apparently enjoyed it. Five years after stepping out of the wilderness, Ishi died of tuberculosis.

Could they have done anything differently? Looking back, Kroeber and his colleagues were haunted by the mistake of exposing Ishi to so many visitors and potential diseases. But aside from that, Ishi’s options were limited and the university may have been the best place for him. First, he could not be returned to the wilds, since his family and tribe were gone and he’d had trouble finding food. Second, the local sheriff put him in jail when he was first found, where he was treated as a circus animal, and it was the university that saved him from this fate. Third, he could have joined other Native Americans in being re-settled on a reservation many states away, but those were not his people or his place.

Did Professor Kroeber and the university researchers use him? Undoubtedly, their association with Ishi furthered their careers. They might have taken better care of him in terms of avoiding as much exposure to disease. But they truly loved him, learned a lot from him, and gave this lonely man a place of belonging for the last few years of his life.

Professor Kroeber (center) with Ishi (right) and an English-speaking member of the related Yana tribe (left).

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_L._Kroeber

Images are public domain