Picture this: You were born as a big fat advertising blimp with an easy life of flying around, showing your Goodyear Tire Company sign for all to see. Instead, when the United States of America entered World War II, you were put into service patrolling the coast for submarines. Worse yet, you were sold to the United States Navy and commissioned as a wartime airship (technically, it lacked a rigid frame, so might be more accurately called a blimp).

They took away your old name, “Ranger” and gave you a new one: “L-2”. And they gave you more work, testing out bombs and so forth. But things were about to get much worse for the blimp formerly known as Ranger. In June 1942, during a practice exercise, another blimp crashed into you five miles off the shore of New Jersey, sending 13 people into the ocean (all but one of them died). That was the end of you.

But there was still hope. Is there such thing as re-incarnation? There was another…Ranger.

Goodyear had another blimp made with the name “Ranger.” Once again, it was sold to the U.S. Navy and re-commissioned, this time with the new name: “L-8”. While ferrying supplies to ships and watching the coastline was not as comfortable as flying around to display the Goodyear logo, protecting the country was a noble occupation for a blimp.

These are two pictures of another L-class blimp. You can see that it was called Resolute in the Goodyear photo, but the second picture shows the U.S. Navy's L-4 designation. And if you look closely there, you can see the old Goodyear "Tireguard" word painted over by the Navy also.

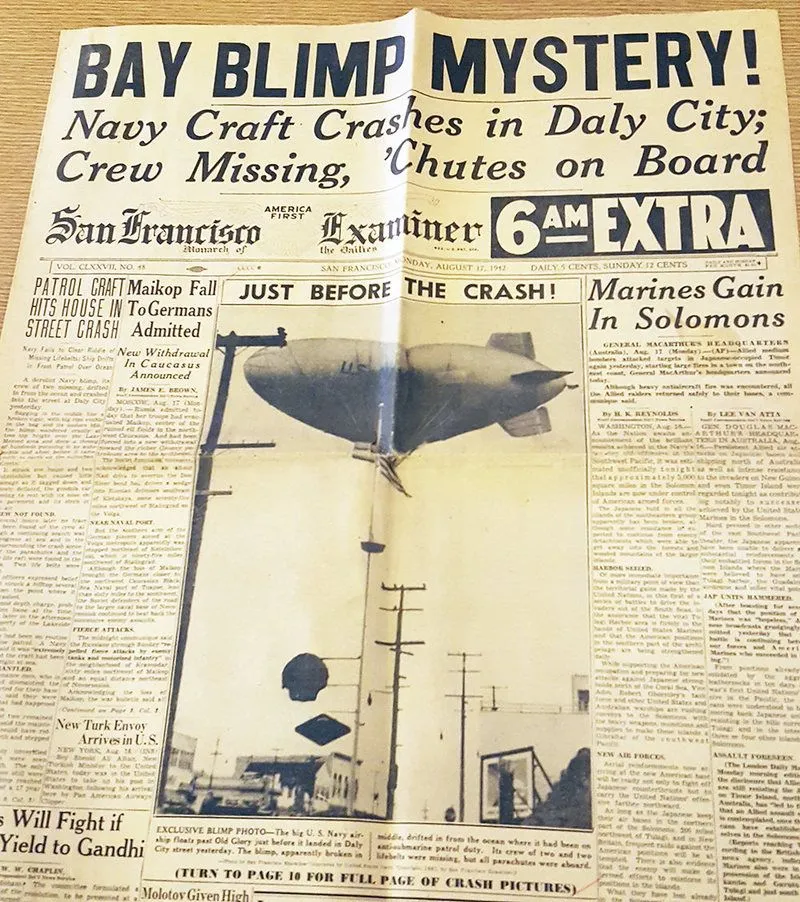

But trouble came in August 1942 when L-8 made a routine trip out over San Francisco to scout the coast. Its bag full of 123,000 cubic feet of helium, the blimp left the base on Treasure Island with an experienced two-man crew. Over the Pacific, L-8’s pilot and co-pilot radioed that they were investigating a suspicious oil slick in the water. They dropped two smoke bombs to mark the location.

This being the Pacific Ocean in 1942, an oil slick might mean a Japanese submarine. These blimps were specifically tasked with investigating such anomalies. In fact, that’s why L-8 was equipped with two bombs known as depth charges (they would only explode after being dropped underwater).

But that radio communication was the last time anyone would ever hear from the crew of L-8.

The crew of a nearby fishing boat saw the smoke bombs and realized the blimp might be about to bomb a sub, so they pulled in their nets. Multiple ships watched it dip as low as 30 feet over the water, taking a close look. But after circling the area for an hour or so, the blimp left and turned back towards San Francisco, rising steadily in altitude. After more than an hour of radio silence, two planes were sent to search for the blimp.

Three hours after its last communication, an airline pilot noticed the blimp flying over the Golden Gate Bridge. It was very high, near its 2,000 foot altitude limit. L-8 was spotted again later, further to the south, and one witness reported that its bag was sagging badly in the middle. Later, five hours after its last radio broadcast, the blimp approached Ocean Beach at the southern end of San Francisco’s Pacific Coast.

The blimp was still flying, but it was drifting. L-8’s bag was bent into a V shape and it came in low, hitting a cliff right near the beach as it made landfall. It dropped one of its bombs, which thankfully did not hurt anyone because depth charges only explode under water pressure. L-8 scraped the top of someone’s house, getting stuck in some utility wires that gave off sparks, finally crash-landing on a street in Daly City, a few blocks south of San Francisco. The blimp was surrounded by onlookers by that point.

The door was open and its cabin was empty.

There was no one aboard. And since then, no one has ever solved the mystery of what happened to the disappearing crew of L-8. In the end, the Navy gave the car (cabin) section of L-8 back to Goodyear. But that was the end of the second Ranger blimp as we know it.

One year. Two blimps named “Ranger”. Two strange accidents. That’s one way to get into the history books.

But you won’t believe where I picked up the trail of these two blimps: under the Wikipedia entry for “Letters of marque.” It seems these L-class blimps have another blip in the history books.

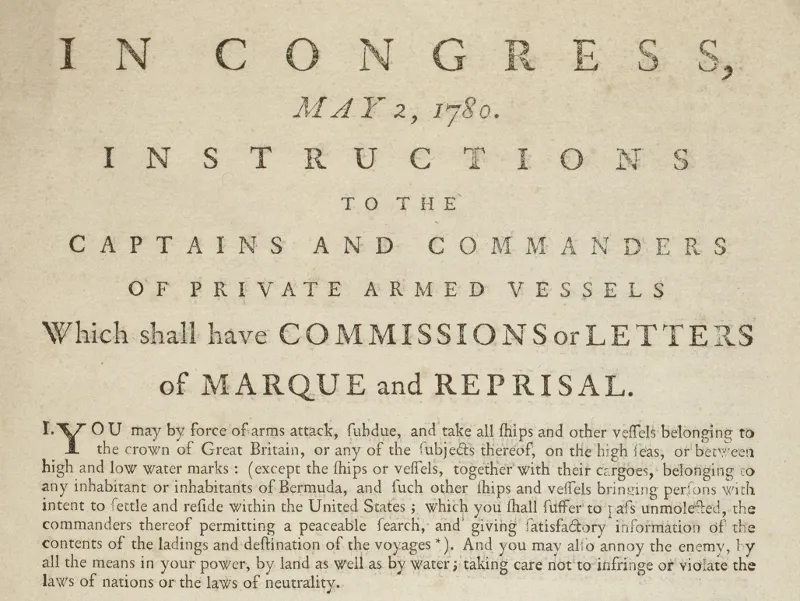

Before being commissioned by the Navy, they may have been privateering. Privateering is piracy with a license. That is where a government authorizes a private party to attack an enemy vessel. Once captured, the privateer usually can claim a share of the prize. One of history’s most famous privateers, for example, was Sir Francis Drake. Under a letter of marque from Queen Elizabeth I, he attacked Spanish sailing vessels and came away with a great deal of their precious cargo. Once he had returned to England, the Queen took her share.

Letters of marque issued by the U.S. Congress authorized privateering vessels in 1780.

While the Goodyear Tire Company still owned the L-class blimps in the 1940s, they began flying missions for the Navy. They were armed with rifles. Some accused the Goodyear blimps of operating as privateers. However, under the U.S. Constitution, only Congress has the power to grant letters of marque, so the Navy would not have been able to make such an authorization on its own. The issue was resolved when Goodyear sold the blimps to the Navy, which then exercised full control over them during the war.

And lost a couple of the Rangers in 1942.

Sources:

http://www.historynet.com/mystery-of-the-ghost-blimp.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letter_of_marque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L-class_blimp

http://www.airships.net/goodyear-blimp/

https://welweb.org/ThenandNow/USN-L8.html

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-1942-ghost-blimp-that-bewildered-a-california-town

In subsequent decades, Goodyear blimps became a common sight at sporting events, often providing some aerial camera views of the field and environs. Creative Commons via Flickr.com by Paul Walsh. Other images public domain, except for the Drake image, which is used under a Creative Commons license, courtesy of the New York Public Library.