Today it was my great pleasure to introduce my "English and American Literature" class to the delights of Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542), courtier to Henry VIII, and a jilted old flame of Anne Boleyn.

Thomas Wyatt Introduces The Sonnet To England

It was Thomas Wyatt who, on his return from a diplomatic mission to Italy, introduced the Petrarchan sonnet into English poetry. Yet his style is that of the frank and robust English gentleman, or at least, as frank as one could be as a courtier in Henry's retinue without risking the loss of one's head.

A Childhood Friend (And More?) Of Anne Boleyn

The Wyatts and the Boleyns were neighbours and Thomas and Anne had known each other since childhood. Anne haunts Thomas Wyatt's poetry - sometimes as a ghost in full view, at other times, more like a poltergeist rearranging the furniture in the chamber of his - and our - imagination.

Take these lines from Wyatt's poem, "Whoso List [i.e. "Desires"] To Hunt":

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck round about:

Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.

["Noli me tangere" = "Touch me not," a quotation from the Vulgate Latin version of the Gospel of John, 20: 17.]

Here Wyatt is as frank as he dare be about the frankness with which Anne declared herself by wearing his necklace to be the King's private property.

The Brunette Who Set The Country In A Roar

If there be any doubt as to the identity of the woman who haunts his poetry, Wyatt's late sonnet in its original form is his most frank description of the lady in question. By the time he wrote the sonnet he had found consolation with his live-in mistress, Elizabeth Darrel (the "Phyllis" of the sonnet), who, he claims, replaced the "brunet[te]" (Anne) in his affections:

If thou ask whom : sure, since I did refrain,

Her that did set our country in a roar,

Th' unfeigned cheer of Phyllis hath the place

That Brunet had ; she hath, and ever shall.

What other brunette was there in Thomas Wyatt's lifetime who set the whole nation in a roar apart from Anne Boleyn?

Well, to be frank, I did not mention any of that preamble to my Japanese vocational college students. I doubt that any of them had heard of Henry VIII, let alone Anne Boleyn, before this afternoon.

Instead, I approached the topic from the opposite angle, via one of Wyatt's poems that I had set for the class.

Never Heard Of Elvis, or Noah, Let Alone Henry VIII

Keep in mind that most of this generation of Japanese students have never heard of Elvis Presley.

Yesterday, in my communication classes I discovered that nobody had ever heard of "Noah's Ark," except one, and she only knew it because she's a fan of the Japanese "Detective Conan" animation series and "Noah's Ark" is the name of a computer generated "artificial mind" developed by a ten year old prodigy...

But I digress...

The aim of my literature class this afternoon was simply to get the students to engage with one of Thomas Wyatt's most famous poems, the three verse poem written in Chaucerian "rhyme royal" (with an ABABBCC rhyme scheme), They Flee From Me.

Here is how I ran the lesson.

I told the students that the poem began with the word "They" and I wanted them to think about who or what "They" could be, based on the first verse.

Then I asked the students to think of another way to say "run away" in one word.

One student wittily suggested just "run." Then, to my delight, one of the best students said, "flee," which was the answer I was looking for.

I wrote the first two words of the poem on the board, and then dictated the first verse to the students.

They flee from me, that sometime did me seek

With naked foot stalking in my chamber.

I have seen them gentle, tame, and meek

That now are wild and do not remember

That sometime they put themself in danger

To take bread at my hand; and now they range,

Busily seeking with a continual change.

Next, they had to compare their dictations in pairs or small groups and discuss what "They" referred to.

They dictated the verse back to me and I wrote it on the board.

I pointed out the opposition of "tame" and "wild" and explained some of the vocabularly, and acted out the process of offering bread in your hand. The students began to suggest various animals such as cats (prompted by my explaining the word "stalking"), dogs, rabbits and we talked about whether or not those animals would take "bread" from one's hand.

We had some fun with the word "chamber" as I pointed out that it came from the French word for room, "chambre" whereas the more common word "room" comes from the German word "Raum".

Next, I told them that we would find out more about who or what "They" were in the second verse, and dictated it, leaving just one word out to see if anybody could supply it:

Thanked be fortune it hath been otherwise

Twenty times better; but once in special,

In thin array, after a pleasant guise,

When her loose gown from her shoulders did fall,

And she me caught in her arms long and small,

Therewithal sweetly did me [----]

And softly said, "Dear heart, how like you this?"

That verse is quite frank, yet only one student was able to supply the missing word - the same student who had given me the word "flee." And she said the word so softly (and behind her surgical mask, which we all still have to wear in class) that I had to double check that she had said "kiss." She repeated the word more clearly, and received a round of applause from the class.

At this point I frankly explained to the students that the poet was a courtier who met a lot of young ladies of the court of the king (not yet explaining which king), and that the opening word, "They" referred to those young ladies of the court.

We wondered whether "Twenty" referred to the number of young ladies who had stalked into his chamber, but concluded that it was more a measure of how much better things were in those days compared to now... and that there was ONE special lady whom the poet describes in the second half of the stanza...

Now I dictated the third and most challenging verse:

It was no dream, I lay broad waking.

But all is turned, thorough my gentleness,

Into a strange fashion of forsaking;

And I have leave to go, of her goodness,

And she also to use newfangleness.

But since that I so kindly am served,

I fain would know what she hath deserved.

Most of the young ladies in the class quickly cottoned on to the meaning when I explained that (according to the poet) the lady in the second stanza had quickly grown bored of the gentleman because he had been too tiresomely polite and gentle (lacking the vigour of a Petruchio, for example) and that she had moved on and now treated him with cold and disdainful politeness, for which he was wondering how he could get his revenge!

The last part of the class was given over to telling the students about Thomas Wyatt and Anne Boleyn, explaining that she later became the second wife of King Henry VIII, whose image amused and impressed them as they google searched henry viii on their phones.

They were goggle-eyed as I told them about Anne's grisly end and how her ghost haunts the Tower of London.

I concluded by telling them about Henry's six wives, their names and their fates, which turns into a nice couple of easy to remember patterns that finished off the class with a bit of drama:

| Catherine | Divorced |

| Anne | Beheaded |

| Jane | Died |

| Anne |Divorced |

| Catherine | Beheaded |

| Catherine | Survived! |

One big sign that the lesson had gone well was that the students stayed in their seats and attentive when the bell sounded as I raced to complete the story of the six fates of the six wives!

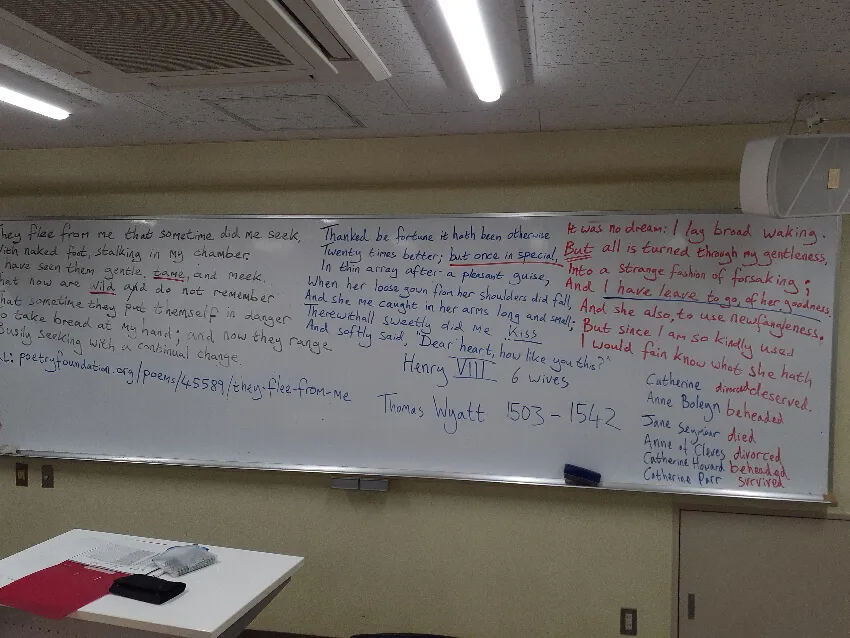

And here is how the board looked by the end of the lesson!

And that, to be frank, was that! A most enjoyable afternoon, and another day's teaching done and dusted.

Cheers!

David Hurley