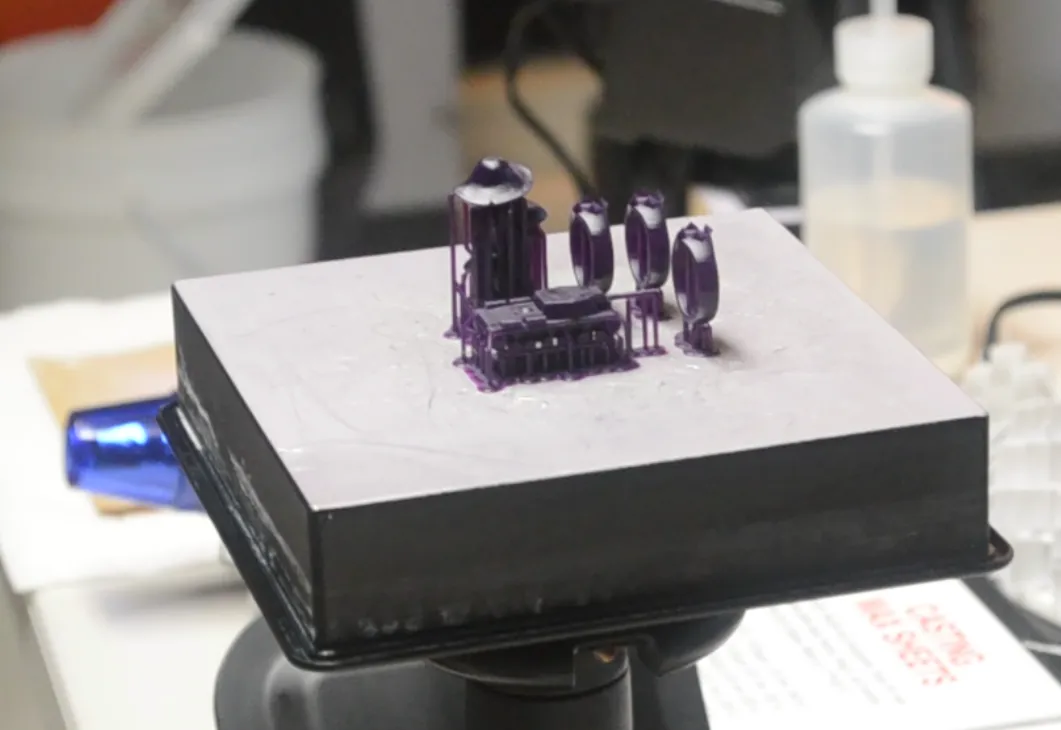

3D printing opens up many new possibilities for intricate metal fabrication. While there are 3D printers that print directly in metal, such as selective laser sintering (SLS), those machines are extremely expensive, and the predominant method for using 3D printing in metal fabrication is to print wax patterns for investment casting. This, as you may know, as what I'm doing.

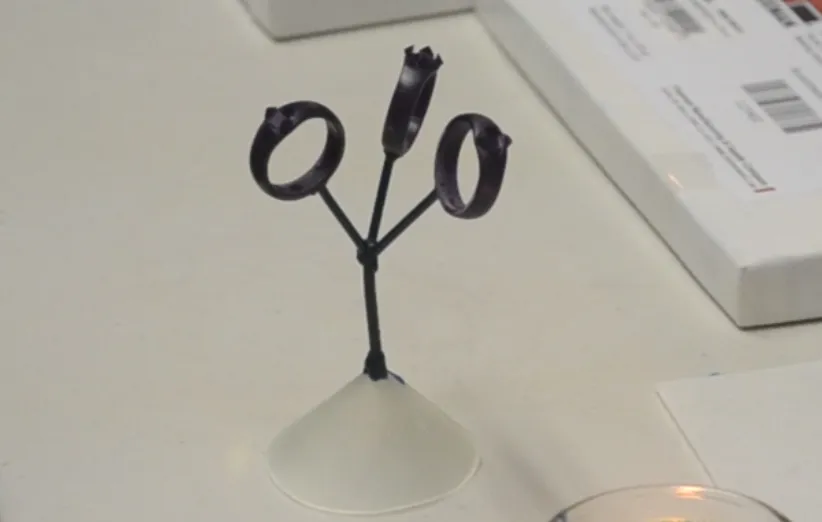

This is the third part tree I have constructed, with three rings on it. I had previously attempted casting this same ring:

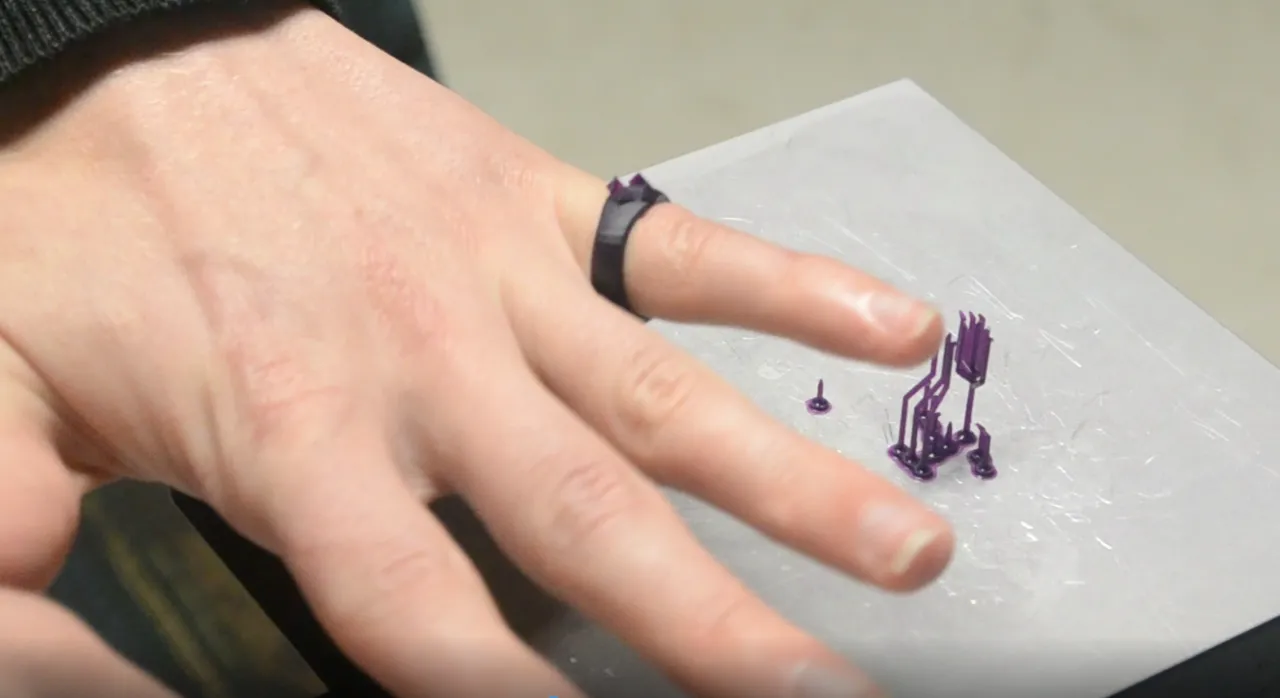

...which you may have seen before, along with my coronavirus survival pendant:

This was my first attempt at casting. Unfortunately, I tried using regular plaster to cast this one in lead-free crown pewter, which is mostly tin, under the assumption that plaster would survive the relatively low temperature. Unfortunately, even if plaster can survive molten tin, it obviously can't survive the much higher temperature of the wax burnout cycle. The result was that the mould cracked:

The cracks ran throughout the plaster and, when I poured in the molten tin, it started leaking out. Clean-up was a bit of a pain, but I discovered that the tin did, indeed, reach into all the little pockets that form the s-proteins of the virus. Therefore, I don't think I need to add more wires all over the place to reach such areas. I have a much better model that will provide the ultimate test of that, and will determine whether or not I need to add a vacuum system to my casting setup.

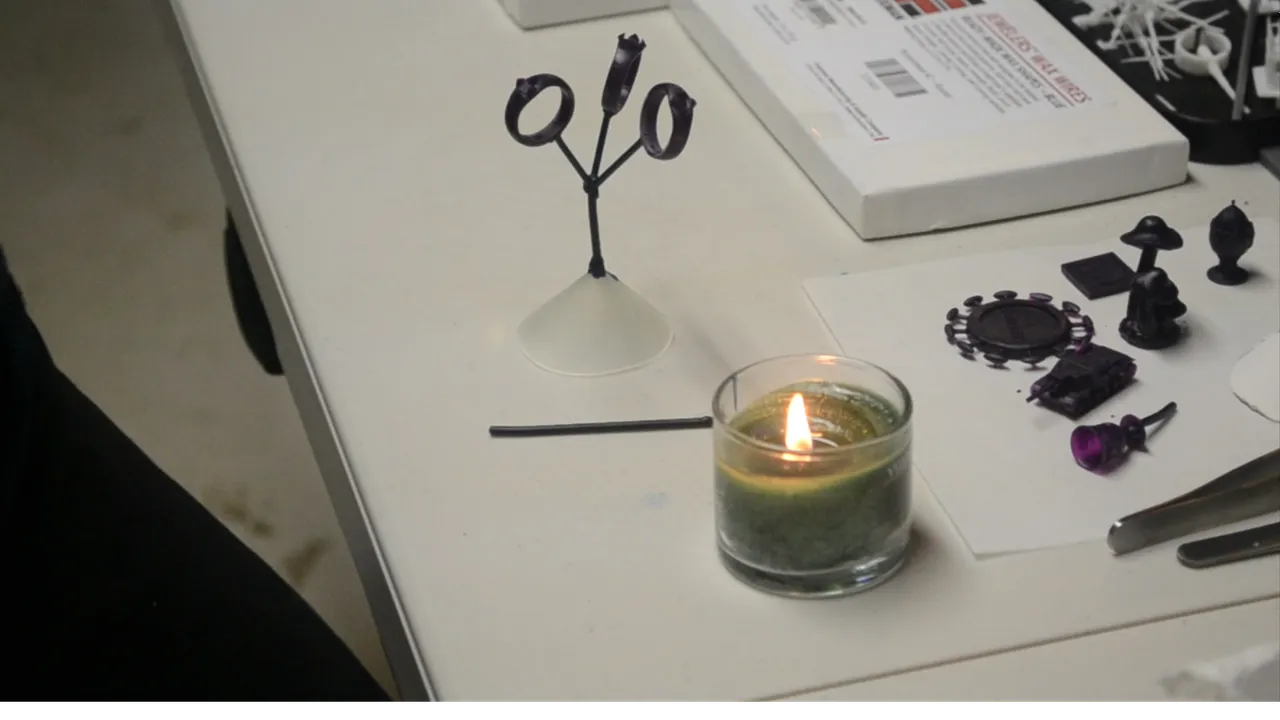

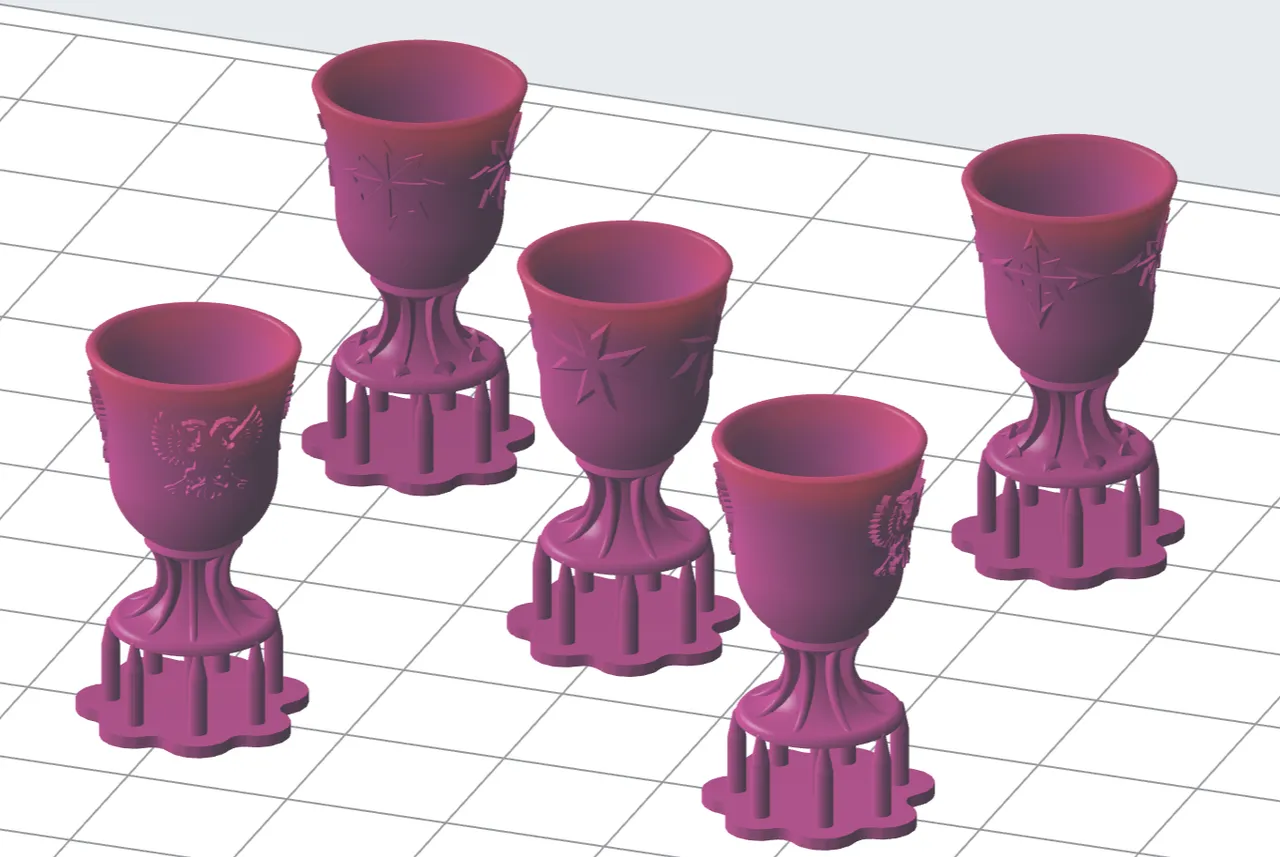

The second part tree, which has just been burned out as I'm typing this, is of these cute little chalices. I've showed these designs before:

I decided to print four of these along with one of my custom zipper pulls:

This time, I'm using Ransom & Randolph Plasticast for the mould. I'll save trying to make my own investment material (plaster with additives) for later, such as if I ever scale up and start doing tons of casting.

During the pouring process, I tilted the tree to release the air bubbles trapped underneath the cups. You know how you can submerge a glass upside down in water, and there will be a bubble of air at the bottom of the glass? That is exactly the sort of thing I don't want. As it is, I have no idea what I'll end up seeing. We will all find out tomorrow.

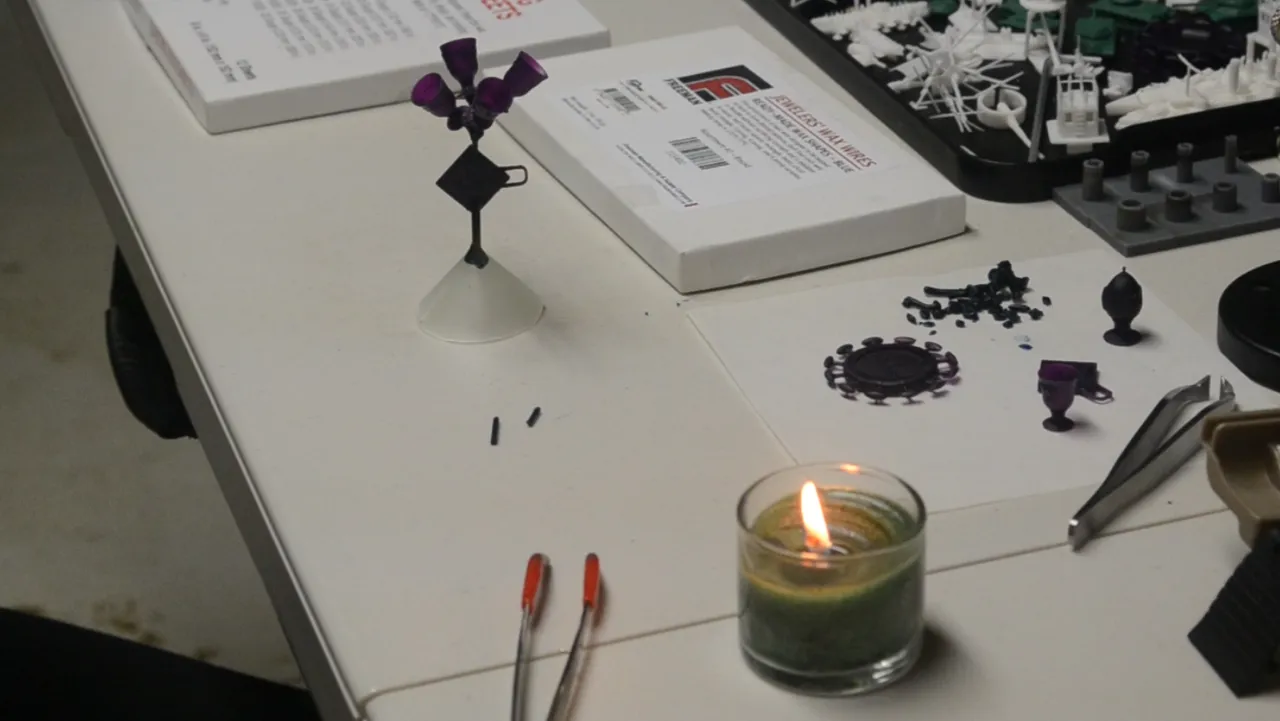

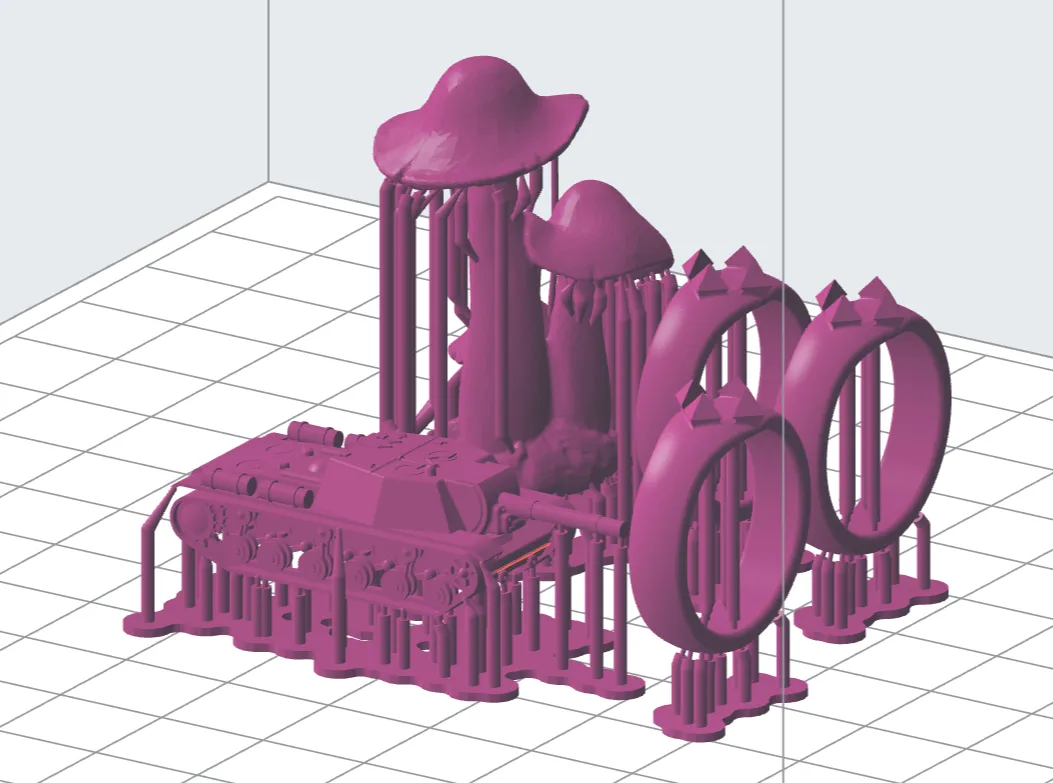

The rings you saw at the beginning will be cast in bronze. I printed them alongside a 1:220 scale SU-152 (tin tanks, anyone?) and a mushroom that I found on Thingiverse many years ago.

I'll definitely try casting the rings in bronze before casting the SU-152 in tin. I'm not sure what I'm going to do with the mushroom. If tomorrow's casting goes well, then I may try casting the mushroom in bronze, just to see what casting at a much higher temperature is like. After all, bronze glows when it's molten; tin doesn't. There is one other important consideration - the mould must be kept hot before casting, usually a few hundred degrees below the metal's melting point. This way, the molten metal will not solidify too fast, and when it does finally solidify, the whole thing is quenched, and the investment shatters, revealing the metal part tree almost immediately (some clean-up is still required, and you'll see that in a later post).