Last week, China published yet another set of disappointing economic numbers. Not only was GDP growth lower than was expected, but year on year inflation came in at 0%, sparking some anxiety among Chinese policy makers and analysts about the prospect of China falling into a deflationary spiral akin to what happened to Japan 30 years ago. So in this article, we're going to take another look at China's struggling economy, the deflationary risks and whether China could really become the new Japan.

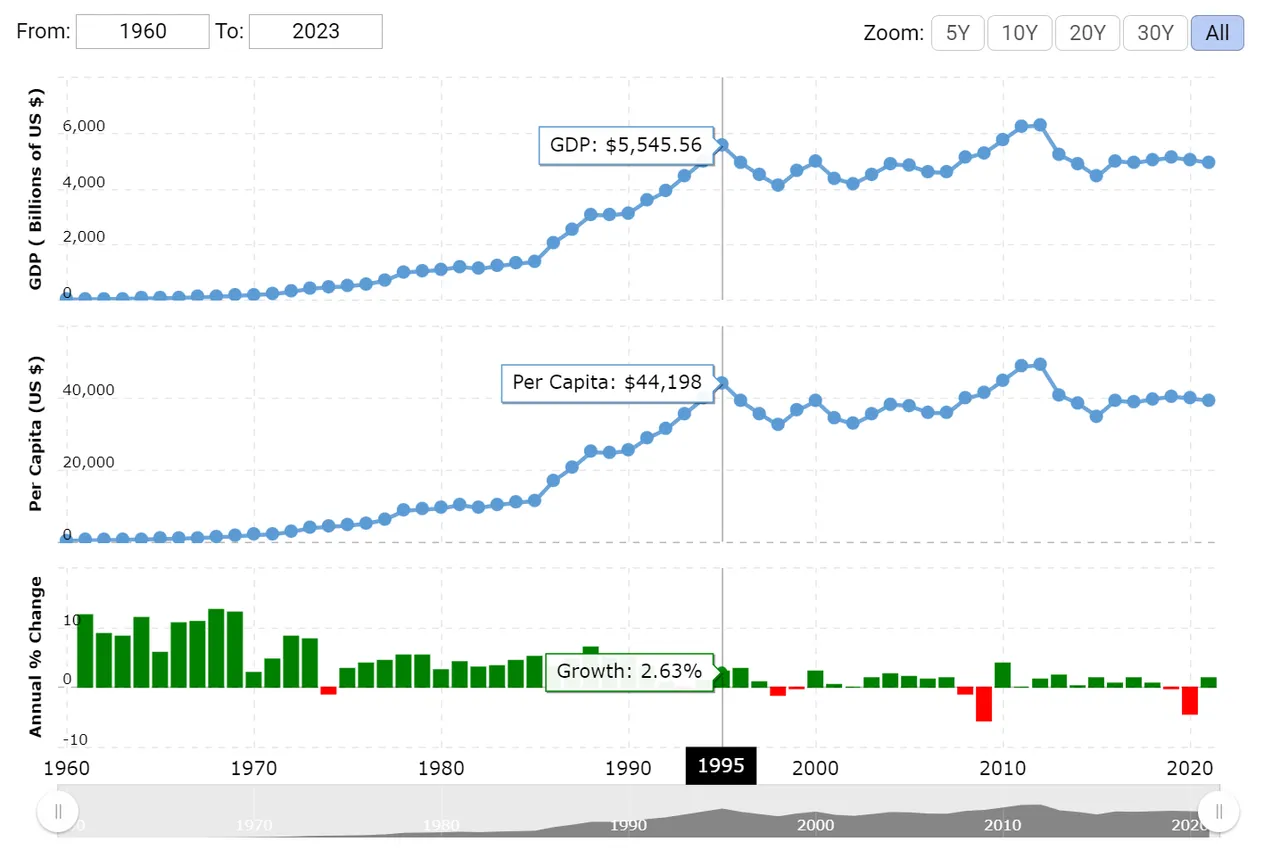

Before we get into whether China might end up like Japan, I've first got to explain to you exactly what happened to Japan in the 1990s. Now, what happened in this time period is still subject to academic dispute, but the broad outlines of it are that after decades of rapid economic growth in the early 90s, Japan experienced a massive financial crisis that the Japanese economy has never quite recovered from. For context in the postwar years Japan experienced many decades of rapid economic growth in a period dubbed the Japanese Miracle. From 1955 to 1990 Japanese growth averaged 6.8% per year and GDP multiplied eight times, with growth falling below 3% only once during the 1974 oil shock. Interestingly, Japan's economic success created some tensions with America in much the same way that China's has. Americans blame Japan for stealing American manufacturing jobs, members of Congress literally gathered on the Capitol lawn to smash Japanese electronics with sledgehammers and American analysts started anxiously predicting that Japan's economy would overtake America's sometime in the early 2000. Clearly, then, there are parallels between America's anxiety about Japan in the 80s and the anxiety directed towards China today.

Some of the discourse was also eerily similar. The Atlantic ran a piece arguing that the US needed to, quote, contain Japan. There were books written about Japan's alleged artificial intelligence capabilities and Donald Trump even took an ad out in The New York Times warning Americans that Japan was stealing American jobs. Anyway this anxiety subsided in the 90s when Japan experienced an enormous economic crisis and there were basically three stages to this crisis. The first stage came in the late 80s when rampant speculation inflated a massive asset price bubble. Between 1984 and 1990 Japan's stock index which covers 225 of its largest publicly owned companies nearly quadrupled and house prices basically tripled. Similarly, between 1983 and 1991 commercial real estate valuations literally quintupled. Now, the second stage of this crisis came in the early 90s when the bubble itself burst. Now, the first signs of this came in 1990 when the stock market started declining, and by 91 it had come down nearly 50% from its previous year peak and soon after house prices also started falling. Residential house prices fell by more than 50% in the decade after 1990 and commercial property prices fell by something like 85%.

The third and final stage comes some decades afterwards, when Japan suffered a sustained period of economic stagnation and perhaps most significantly, deflation. This period, after Japan's asset price bubble burst is sometimes known as the lost decade. But given that growth and inflation both remained close to zero until very recently, it's probably more accurate to describe this period as the lost few decades. Now, no one knows for sure why Japan was unable to get out of its economic funk for so long. But perhaps the most compelling account came in the early 2000, when Japanese American economist Richard Koo wrote a book called The Balance Sheet Recession. Essentially, Koo argues that Japanese households and companies had taken out too much debt when asset prices were rising. So when asset prices fell in the early 90s Japanese individuals had to focus on paying down their debts. In other words, repairing their balance sheets.

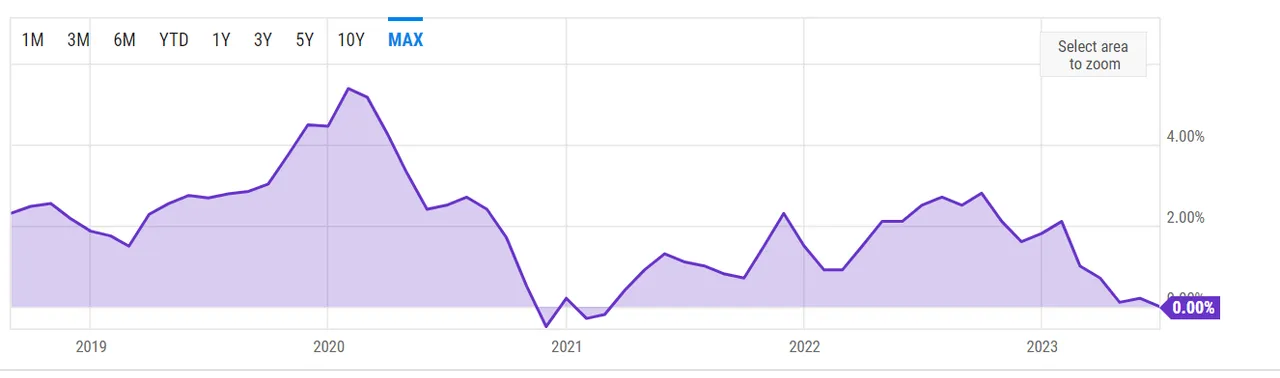

While this might make sense on an individual level, for example if the price of your house goes down steeply, it makes sense to focus on paying off your mortgage in order to reduce the risk of bankruptcy, if everyone in the economy starts doing this at the same time then the economy stagnates. This also explains why the Bank of Japan was unable to get the economy going with its unorthodox monetary policy, which included bringing interest rates below zero and buying up loads of corporate debt. If Japanese households and companies are still focused on debt minimization instead of profit maximization then cheaper borrowing rates were never really going to change anything because they don't want to borrow more money anyway. All in all this lack of demand meant that prices never recovered, pushing Japan into a chronic deflationary state. While this might sound good, especially if you're living in a country that's struggling with high inflation right now, actual deflation is pretty terrible news for any economy because it creates a downward spiral of self-fulfilling recessionary expectations by discouraging borrowing.

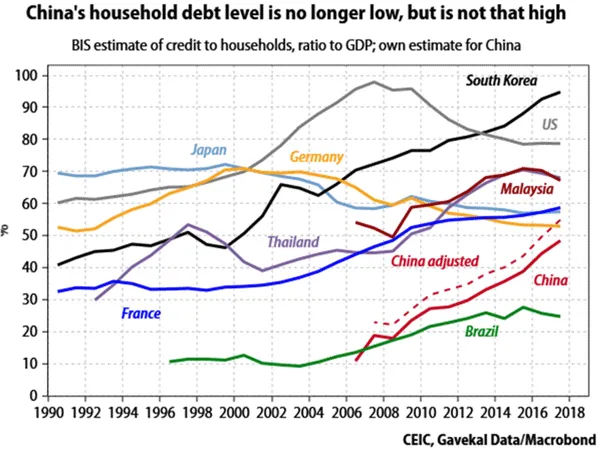

Anyway, that same Richard Koo, as well as other analysts, have recently been warning that China is on track to suffer its own balance sheet recession. Noting the glaring similarities between China today and Japan 30 years ago. Like Japan in the 80s and 90s, China has its very own debt fueled property bubble, an export driven economy, weak consumer demand, an aging population and rising youth unemployment rates. And maybe proving the point chinese companies and individuals are already starting to reduce their borrowing. While this might sound like a good thing, given the debt pressures on certain sectors of the Chinese economy, it might also be a symptom of the fact that Chinese individuals and companies are already drowning in debt and are now focused on debt minimization instead of profit maximization. And if that's the case, then the Chinese economy is primed for a balance sheet recession and potentially a period of prolonged economic stagnation akin to what happened in Japan.

Similarly, like Japan, interest rate cuts by the PBoC have been unable to stimulate growth in China, and inflation is worryingly low. In fact, year on year inflation came in at 0% in June. Nonetheless, despite these similarities there are respects in which the Chinese market is significantly different from Japan. For starters, the Chinese government has a tighter control over the economy than the Japanese government did and it's possible that the CCP's foresight and more interventionist tendencies might stop China from falling into Japan's deflationary trap. And so far this does already look plausible. While China's property market has slowed or stagnated we haven't seen the same steep decline in prices akin to what happened in Japan, at least for now. But perhaps the main advantage the CCP has is that they've already seen what happened to Japan and Chinese policymakers are aware of the threat that a balance sheet recession poses. But despite this knowledge, the CCP are still presented with a difficult dilemma. The most obvious way to get out of a balance sheet recession is lots of fiscal stimulus. You just give everyone tons of money until they stop worrying about their debt. In the Chinese case, for example, you could give loads of money to property developers to improve homebuyer confidence and reduce developers debt burdens. And this is actually what Koo has recommended. But while this might work in the short term, it will only perpetuate the unbalanced growth that the CCP has become so worried about recently.

Sources:

- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1989/05/containing-japan/376337/

- https://ycharts.com/indicators/china_inflation_rate

- https://carnegieendowment.org/2010/03/18/japan-s-past-and-u.s.-future-pub-40356

- https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/JPN/japan/gdp-gross-domestic-product

- https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/ilanbenmeir/that-time-trump-spent-nearly-100000-on-an-ad-criticizing-us

- https://www.ft.com/content/a3564812-363c-11e7-99bd-13beb0903fa3

- https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-136-the-legacy-of-shinzo

- https://tradingeconomics.com/china/inflation-cpi

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-06-29/inventor-of-balance-sheet-recession-says-china-is-now-in-one

- https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/JPN?zoom=JPN&highlight=JPN

- https://www.hvst.com/posts/chinese-credit-collapse-is-imminent-w6nTkjxr