This series of posts will insure that these authors' works live on in living memory.

If only a few.

Don't lose hope.

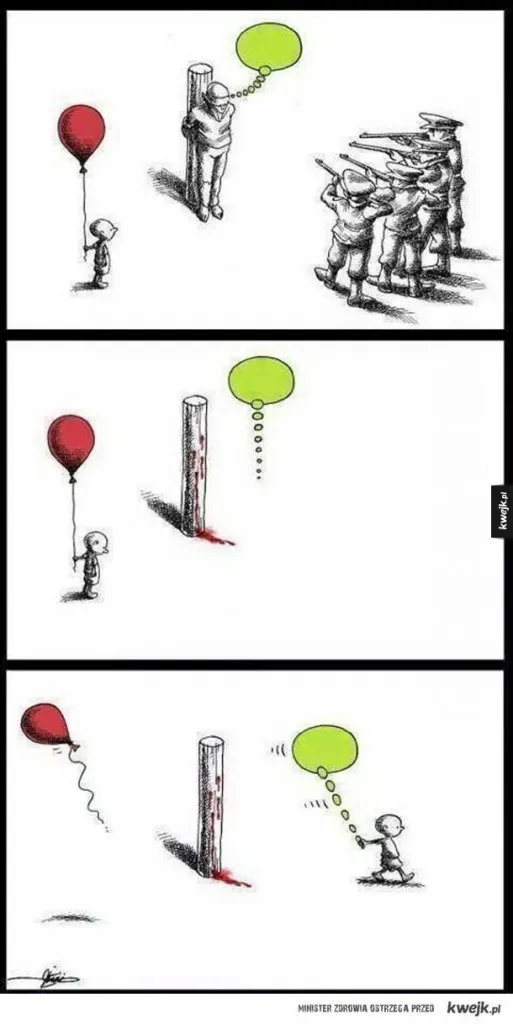

Rule by force has had it's day.

We just have to survive its death throes.

There is a reason these authors are not in the modern curriculum.

The Gang's Finale: For a Few Bullets More

After Chantilly, the gang split the proceeds and parted company.

Soudy, seeking some relief from his tuberculosis, traveled to Berck, a seaside health resort.

With his paleness and long interludes of coarse, rattled coughing no one expected to him to rejoin the gang.

Everyone else found safe houses and laid as low as possible, fully recognizing that anything appearing to be out of the ordinary could bring the attention of the neighbors and probably the police shortly thereafter.

The gang recognized that huge rewards were being offered for any information and that in working class areas the temptation must have been intense to turn informant.

Further the Sûreté was doing their best to plant as much suspicion as possible within anarchist circles, driving home the point made by Jouin that the bandits were "discrediting a great ideal," thereby casting the police in the unlikely role of guardians of the purity of anarchism.

The first to fall was Soudy who had been staying with friends at Berck.

Jouin had been fed information detailing his whereabouts and as Soudy emerged from his friends [...] and walked towards the train station five policeman jumped him.

An unidentified informant was paid 20,000 fr for the betrayal.

Raymond La Science was next.

He had taken refuge with an anarchist couple Pierre Jourdan and his lover Louise-Marcelline in Paris's 9th arrondissment.

Louise-Marcelline was evidently the unidentified informer in this case, and as La Science appeared outside the apartment early one morning wearing cycling gear and with a new racing bike he was apprehended.

A search of his cycling shorts revealed sixteen one hundred franc bills and two loaded Browning 9mm pistols.

Monier was next, he had taken to hopping from hotel room to hotel room and had been impressively assiduous in his efforts to remain invisible until he met some anarchist friends for a meal in the boulevard Delessert; the meal party included Lorulot who was well known to the police and they had been tracking him for several weeks.

The gambit paid off, Monier was immediately identified and followed back to his hotel.

Unwilling to wait for him to come out the police forced their way into his room and due to surprise took him without incident.

They noted that he had two loaded 9mm Brownings on the bedstand and had they been less quiet the arrest could have gone very differently.

Bonnot and Garnier would be less easy to take unawares, and they were both poised to take as many cops as possible with them into the abyss.

Bonnot had been staying with a friend Gauzy above his second-hand clothing store.

As time went on, Gauzy had become more and more uncomfortable with the situation, and Bonnot, unwilling to remain in a darkened room for hours on end had been out walking several times.

Meanwhile the Sûreté had patched together some loose leads and decided that many of the "Second hand" shops in working class areas may well be operated by fences, they had also linked a number of these shops to gang members.

Gauzy had finally prevailed upon Bonnot to find other accommodations, though Bonnot dithered away a day or two deciding what to do.

Gauzy was then surprised to see four bowler hatted men enter his shop on the day Bonnot was to have left, timing it seems was neither on his side nor Bonnot's.

Jouin introduced himself and stated that he had a warrant to search the premises, and probably hoping that Bonnot had jumped out the window, Gauzy led the detectives upstairs to his apartment.

Gauzy fumbled with the key as he unlocked the door and stood back for Jouin and Colmar to enter, as they did Bonnot who had been reading a paper by the window jumped up and grabbed for a small caliber pistol in his jacket pocket.

Jouin was on him in an instant, they wrestled and Bonnot, finally getting the pistol in hand, fired three shots into the detective, the final bullet through the neck killing him instantly; a perfectly appropriate Stirnerian moment; the triumphant individual destroying the lead coil of the venomous state.

A fourth shot, probably fired from the floor, killed Colmar.

The third detective Robert dashed into the room and finding Colmar breathing shallowly hefted him on his shoulder and carried him down the stairs.

Bonnot, shoving Jouin's corpse off him ran down the hallway, through a window and into the street.

His forearm, grazed by a bullet, trailed blood as he ran.

Bonnot spent three uncomfortable nights in the open, finally making it to the garage of an anarchist at the fringes of the gang, Jean Debois, in Choisy-Le-Roi where he spent the night.

Dubois was up early working on a motorcycle when sixteen armed men pulled up in several autos and rushed the garage.

Dubois pulled a pistol and shot the detective closest to him in the wrist, but the other cops were ready and he was met with a hail of bullets, one striking him in the back of the neck killing him outright.

Bonnot, wakened by the din from downstairs, grabbed a gun and walked onto a small balcony overlooking the yards and stairs only to find the detectives just ascending to the room.

He fired catching the lead cop in the stomach, and then ducked back into the room to avoid the bullets flying at him.

The detectives summoned help from anywhere they could, including two companies of Republican Guards, a group of locals with pitchforks and shotguns (no, really - pitchforks), and further reinforcements from the Sûreté.

The battle lasted all morning with thousands of bullets tearing holes throughout the room where Bonnot was firing from, and Bonnot himself occasionally walking out on the porch to take a few well-aimed shots at his attackers.

By noon, with the battle effectively a draw; the Sûreté men decided to try and blow the garage up, with Bonnot inside.

A cart piled with mattresses was rolled towards the building, the dynamite fuse lit and placed next to the wall.

The fuse sputtered and died causing the cart once again to roll forwards so that the fuse could be relit - this time successfully, though the charge was insufficient to destroy the garage.

Third time's a charm, with the dynamite charge this time large enough to level the building.

Bonnot, still alive though barely breathing was rushed to the hospital, but died en route.

Two days later Bonnot and DuBois were buried surreptitiously in the paupers of the cemetery as Bagneux.

The graves were left unmarked so as to preempt any remembrance ceremonies.

This left Garnier and Valet at large and the Sûreté detectives were justifiably concerned.

Garnier had sworn in his letter to Le Martin to deal swiftly with informers and he was serious about the threat.

One of the men whom Garnier was sure had sold information to the police was Victor Granghaut, who had prearranged Carouy to stay with him; he was subsequently arrested the very same night.

Garnier had caught a train to Lozere and there waited for Victor to return from work.

Victor and his father were walking back home from the station when Garnier stepped out of the bushes and in spite of the father's pleading and attempts to protect his son with an umbrella shot him once in each leg stating, "That will teach you to inform on Carouy."

The final battle took place in Nogent, where Garnier, his companion Marie, and Valet had rented a suburban Bungalow.

The two men had been recognized on a bus to Nogent and it didn't take long for the police to identify the house that had been recently rented to three suspicious newcomers.

The illegalists were just finishing preparations for a simple vegetarian dinner when Valet, standing in the back yard taking in the air was accosted by a man wearing a red, white and blue sash who called in, "Surrender in the Name of the Law."

Valet realized immediately that the gaudily clad man wasn't a neighbor, and put a few rounds into the air as he dodged back into the house.

The gun battle that then erupted was fierce even by the standards of Bonnot's last stand.

A cease-fire was called for and the detectives yelled in for the men to surrender.

Marie ran out of the house into the hands of the detectives.

The two anarchists downed water and forgetting their restrictive diet, also drank some coffee to stay alert, though neither had any time to eat.

They then made themselves ready for the end.

They piled the francs they had stolen in the middle of the floor and burned them.

They both stripped to the waist and loaded clip after clip of ammo for the seven 9mm Brownings in their possession, though they had no cartridges for the Winchesters which would have been infinitely more useful, and accurate, in the static gun battle that they were engaged in.

After Garnier had made sure that Marie was safe, the battle rejoined with gusto.

As time went on the odds became increasingly ridiculous, eventually it was estimated that the anarchists were outmanned by a ratio of 500 to 1.

The two managed to hold out to midnight, a full six hours, when with the aid of sappers the house was finally destroyed by a blast of melinite.

The combatants on the side of the law made their way into the rubble and the brave detectives of the Sûreté shot both men, still alive, twice in the head, in direct violations of "standard" police procedures.

The bodies of Garnier and Valet were laid to rest very near the graves of their comrades in arms, Bonnot and DuBois.

Finally, there were those who had been arrested and now face trial, a total of 18 men and three women (Rirette, Marie, and Barbe) - a girlfriend of one of the outlying gang members).

The prosecution knew it had very little to go on, not one of the defendants was talking, the evidence was weak, very circumstantial and ultimately compromised in most cases by shoddy police work.

In fact there was no way that the prosecutors could state with any certainty exactly who had participated in what robbery.

The accused languished in prison until 3 February 1913 when the court began to hear evidence.

In the interim Victor and Rirette began a rapid backpedal from what had been written in l'anarchie, complaining it had been misinterpreted, and that much of what they had said at meetings like the causeries populaires went unrecorded and directly contradicted material that had appeared in printed - basically casting themselves in the role of the "honest intellectual" versus the "criminal illegalist" that the other defendants obviously were.

The final decision of the court and the sentences of some of the defendants follow:

The three women and Rodriguez the fence - Not guilty

La Science, Soudy, Monier - Guilty; Guillotined 22 April 1913

Kibalchich - Guilty; five years in prison, five in exile.

Of the three defendants sent to the guillotine, they all died well (that is, bravely and without regret).

Of the two "honest intellectuals" Kibalchich eventually changed his name (to Victor Serge) and his politics, joined the Bolsheviks, worked closely with the left-communists and later Trotsky only to be deported by Stalin in 1937.

Like his friend Trotsky he eventually made it to Mexico where he died of natural causes in 1947 - though how he avoided the Stalinist ice-pick is hard to fathom.

Rirette spent the rest of her life damning the anarchists as publicly as she could - coming to the conclusion in her memoirs serialized in the bourgeois Le Matin,

...behind illegalism there are not even any ideas.

Here's what one finds there: spurious science, lust, the absurd and the grotesque.

Maybe she did "get it" after all...

Parting shots

The history of illegalism doesn't end here, a few others have stepped forward and picked up the theory and the weapons that death had pried from the moldering hands of the Bonnot gang.

These include the Italian/German Horst Fantazzini, an individualist anarchist, who robbed his way across Europe during the 60s and 70s with a flair as yet unmatched among the criminal classes.

In one holdup he fled successfully on bicycle, he escaped from prison several times, and when a teller fainted during one of his bank robberies he sent her roses the next day.

The press dubbed him the "kind bandit" thereafter.

He wrote an account of his escape from Fossano prison, which was eventually made into a movie Ormai e fatta!

Fantazzini died in 2001 in a prison infirmary.

One of his daughters built a website to commemorate the life and exploits of her father (http://horstfantazzini.net/) which is fun to look through.

As of today, the life and written works of Alfredo Bonnano continues the theory and praxis of illegalism and any one of his articles is worth a read.

In terms of contemporary social movements the Yomango is an ongoing social phenomenon in South America, Spain, and Italy devoted to open socially informed shoplifting conducted en masse.

The movement is going strong and since the world economy hit the skits in 2008 has if anything grown and become more accepted, to the point of being endorsed by several non-anarchist Spanish trade unions, who periodically sponsor mass shoplifting outings for their members.

There are obviously many other forms of illegalism that have been tried and used in the anarchist milieu and the above review is in no way an exhaustive account.

As an example, all forms of squatting are by definition illegal, regardless, the practice is engaged in, and approved of, by virtually every permutation of current anarchist theory or movement, and is usually justified in a conceptual framework that looks and tastes very illegalist.

In a practical sense; not all illegalists are squatters, but all squatters are illegalists.

Continuing on in a pragmatic manner, illegalism also provides some interesting insights into the ongoing conundrum of organization as it applies to anarchism.

Of note is the fact that while Bonnot and company had no formal structure, no rules for decision making, and little to say on the issue of organization, they do seem to provide some answers on the subject.

One of these solutions is the turning on its very head of the question of organization, which usually begins with the question, "what type of structure shall we create?"

The illegalists, however, in the example provided by their activity began with the question what shall we do, what activity is required for the successful realization of this project.

Then based upon what it is that a group is seeking to accomplish, the structure required to realize the activity comes into being.

Each of these solutions then is also tempered by the principle on its ability to realize the needs and desires of the individual, to safeguard her autonomy against the ever present likelihood that organizations will tend to blunt and ultimately deny the sovereignty of individual in favor of the growing power of the collective, especially with the passage of time.

In extremis some organizations exist whose sole purpose is to maintain their own existence, the nation-state is a good model of such circuitous existential theory, and certainly the police and the military are prime examples of the mailed fist that does nothing save preserve the sovereign status-quo, and eliminate any contestation that could lead to either radical internal change (a relative impossibility) or insurrection.

The absurdity of the argument is often laid bare when fundamental principles are used to justify their own destruction.

The Occupy movement, for all its weakness, provided a perfect example of freedom of speech being justified to destroy freedom of speech - you can say whatever you want, just not at night, not in a public park, and not in New York.

Alternatively there is the example of military versus militia organization in the Spanish Civil War; a puzzle that probably accounted for numerous sleepless nights for Durruti and other FAI militants during the late summer and fall of 1936.

In this case the strategic objective of winning the war did little to inform the structure of the militias; rather the decade/century milita configuration was far better suited to either the type of affinity group actions that the FAI excelled at, or at one step remove, the strike or insurrectionary committees, either regional or national in scope, that the CNT had utilized for its industrial conestation or the outright seizure of villages and towns and the inevitable declaration of "communismo libertario".

Durruti, in one of his moments of clarity, voiced the concern that the "discipline of indiscipline" was proving to be an ineffective tactic with which to fight a civil war.

I have no answer as to how the Spainards should have structured their militias, rather I am convinced that their chosen organization was sufficiently flawed as to allow them to lose twice, first to the Stalinists, and then to the fascists.

The simple, elegant illegalist "solution" to the problem of organization was neither new nor particularly innovative.

The raiding parties of the Great Plains tribes were comprised in a very similar manner.

The "solution" then consists of a structure that is temporary - that ceases to exist past the accomplishment of the strategic goal for which the organization was brought into existence.

The organization allowed for each of the individuals involved sufficient input so as to satisfy the need for participation in decisions that affect ones own life, especially those decisions that may lead to the maiming, capture or death of the organizations members.

Each of the individuals involved understood their various responsibilities and that knowledge allowed for tasks to be completed quickly and completely without the need for oversight (administration) nor the attendant operationalizing factor of oversight - discipline, and its sustaining hierarchy motivating principles - punishment and/or reward.

The illegalists also represent one of the last glowing embers of the association of anarchist with utopia; which would be brought back into a raging conflagration some seventy-five years later with an unlikely mixture of anti-civilization, anti-technology theory, the resurgence of combative, mobile affinity groups best exemplified by the "Vermont Family," urban squatters, and the re-discovery and re-popularization of 120 years of anarchist theory and history (including the Situationists and the Frankfurt School) by a well-connected group of writers, journalists and theorists linked together through zines, mail, and who found each other via the ultimate underground print media clearinghouse, Factsheet Five.

This strange mix of theory, personality and history would be brought to a near explosive mass via the catalyzing addition of various meetings and events including the 1986-1989 Continental Anarchist Gatherings (Chicago-SF-Toronto) and the Tompkins Square Park Riot of August 1988.

Grinding back to the 19th Century - Marx and Engels would use the term utopian as a way to criticize and infantalize not only those thinkers who had swum in the waters of socialism, communism, and revolution prior to their arrival, additionally the anarchists, especially Bakunin, would use the term utopian as an insult for all comers as they vied for political pre-eminence among the various population strata most likely to participate in revolutionary upheavals.

In the case of Bakunin the epithet was hurled without acknowledging the obvious and gnawing truth that most of anarchist theory and praxis was, in fact, pretty utopian.

The Paris Commune provided the political upheaval that materialized as the fork in the road that would effectively split the various revolutionary currents into utopian (anarchist) and anti-utopian (Marxist) camps.

Using then select activities of the Commune to illustrate this marked dichotomous political vision and simultaneously as real events that stirred the acrimonious stew then brewing between Marx and Bakunin, lets see what the Communards did that produced such antipathy - for the Marxists the high water mark of the uprising may be the Commune's outlawing of night work for bakers, a solid practical step towards socialism without a blemish of the idealistic or heroic, without any revolutionary mumbo-jumbo that they accused their adversaries of engaging in.

For the anarchists the destruction of the Vendome Column was the insurrectionary act par excellence - with all the possibilities the action entailed, the death (regicide? arcicide?) of imperialism, militarism and nationalism, the proof of the malleability of the urban landscape to meet the needs of people, and finally the outrageous, side-splitting comedy of watching the bronzed, granite, phallus tumble grandly and flaccidly to the ground.

Not surprisingly the author of the night work legislation was Leo Frankel, a devoted follower of Marx, and the destruction of the Column was the brainchild of the artist Gustave Courbet, an admirer of both Proudhon and Bakunin.

Pushing on from the Commune into later European history one sees this dichotomy grow ever more striking, ever more profound.

The anarchists became the midwives of week long Social Republics, of risings doomed before the first shot was fired, of being the guardians of insurrection that is "nowhere" because it is realized and dreamed of everywhere.

In the mind one sees the image of a Spanish peasant unable to read but staring at and moving rough, calloused fingers over the pictures of black flags and various images that adorn the latest issue of La Revista Blanca.

Anarchism is utopian because the anarchist vision is sublime, transcendent; even the poorest, most uneducated worker could viscerally relate to a future where bosses and work had been destroyed in favor of play as the dominant economic activity and a grand illuminating equality of resources, wealth and opportunities to learn and attain knowledge, and finally to participate directly without mediation in decisions that affected one's life.

Unlike the Marxist who envisioned a society very like the one she lived in, only in the communist world the workers were the masters, not the slaves.

Marxism is anti-utopian because the communist vision is of a society where nothing, other than the class makeup of the new bosses, has changed.

The advent and activities of the illegalists, and the concurrent rise of the most possibillist of anarchist tendencies, anarcho-syndicalism, replayed in miniature the split that occurred after the Commune.

In this instance the reinsertion of utopian currents into anarchism, accomplished as the result of the individual writings of Zo d'Axa, among others, was offset by the growth of the syndicalist tendency, including the uptick in the census of various union bodies, especially those associated with the Confederation General du Travail in France, the IWW in the US and Australia, and of course the proliferation of soviets in Russia.

The strength of the syndicalist argument ultimately being contained in the non-utopian, practical method of building unions as the seeds of the new society, and also providing structure as the post-general strike world and how industry would be changed from a generator of profit to a liberator of human aspirations.

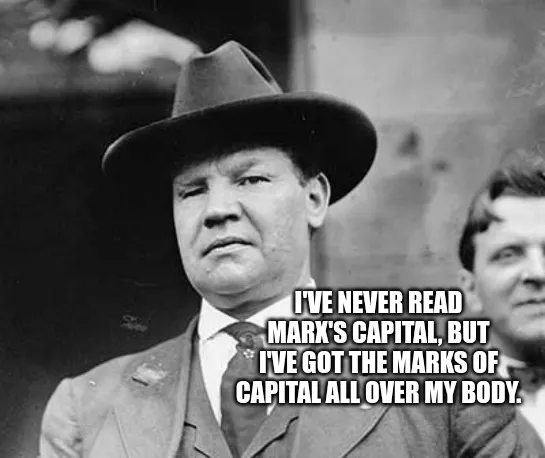

Of interest too is the seeming confusion that reigned at the "top" of these organizations especially the IWW, where Bill Haywood, 2, would respond as to whether he had read Marx's Capital with the snappy rejoinder, "No, but I have the marks of Capital all over my body."

This sentiment is echoed by Joe Hill, who while rotting in prison during the months that the State of Utah was figuring out the easiest way to justify his murder was asked by a local journalist whether he was a Marxist, to which he responded with the simple, and avowedly untrue, "Yes, I am and always have been."

Therefore as syndicalism sought to reject as much as possible the smear of utopianism, the closer the leaders and rank and file edged towards proclaiming the organization and its members Marxist.

The illegalists on the other hand never stood back from the glaring utopianism that characterized much of their theory.

Certainly Kibalchich was sufficiently clear in his theoretics that he acknowledged the basic utopianism that animated much of individualist anarchism, he was equally solid in translating illegalist activities into the living, breathing insurrection that was then being fought out.

Not to be put off to some great event scheduled to occur in the next few centuries, but a battle that was joined daily by the adherents of illegalism, and their supporters.

In this sense the insult to the anti-utopians was two-fold, yes we are utopians, and yes we are utopians operating on the terrain of utopia - now - not in some far-flung future where our children's children will form of the general staff of an as yet unborn insurrectionary militia.

Finally, its also important to note the fundamental violence that such theories do to the Marxists, and some anarchists, who believe that only when the time has become ripe, through the collapse of the wage and profit system, the downhill slide from peak oil, or the moment when everyone, in a vast global pre-frontal cortex explosion of wisdom realizes that the total amount of debt, individual, sovereign, and corporate exceeds the total number of all possible form of profits and incomes with which to make the payments will a revolution become a viable alternative to the species.

As opposed to the very general utopian notion that basic human individual desire and need will be the sole motivating factors that will push the species from where it is now into the great necessity; utopia.

Finally, the real arguments made against illegalism were that of an early, seemingly meaningless death.

So I'll let Marcuse who stood with one foot in Marxism and other in utopia bring this essay to a conclusion:

Under conditions of a truly human existence, the difference between succumbing to disease at the age of ten, thirty, fifty, or seventy, and dying a "natural" death after a fulfilled life, may well be a difference worth fighting for with all instinctual energy.

Not those who die, but those who die before they must and want to die, those who die in agony and pain, are the great indictment against civilization.

They also testify to the unredeemable guilt of mankind.

Their death arouses the painful awareness that it was unnecessary, that it could be otherwise.

It takes all the institutions and values of a repressive order to pacify the bad conscience of this guilt.

Once again, the deep connection between the death instinct and the sense of guilt becomes apparent.

The silent "professional agreement" with the fact of death and disease is perhaps one of the most widespread expressions of the death instinct -- or, rather, of its social usefulness.

In a repressive civilization, death itself becomes an instrument of repression.

Whether death is feared as constant threat, or glorified as supreme sacrifice, or accepted as fate, the education for consent to death introduces an element of surrender into life from the beginning -- surrender and submission.

It stifles "utopian" efforts.

The powers that be have a deep affinity to death; death is a token of unfreedom, of defeat.

Theology and philosophy today compete with each other in celebrating death as an existential category: perverting a biological fact into an ontological essence, they bestow transcendental blessing on the guilt of mankind which they help to perpetuate -- they betray the promise of utopia.