***the cute drawing is taken from an online source."- https://i.pinimg.com/originals/1d/6b/56/1d6b56788e218774b91a0b2d8d04175e jpg

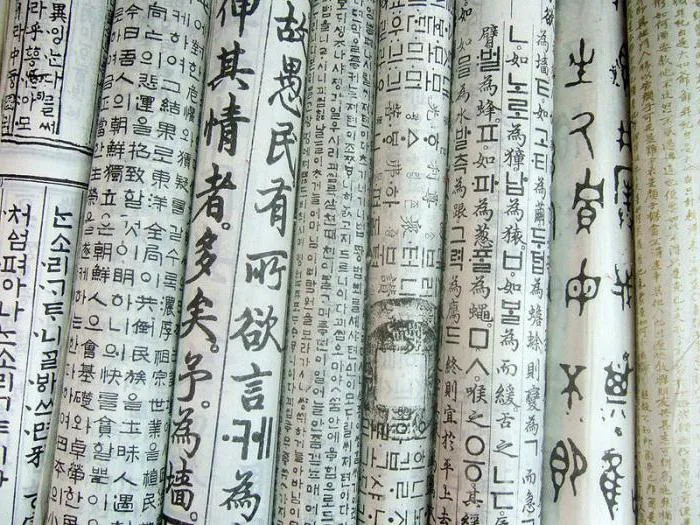

Hancha is the Korean name for Chinese characters and words whose pronunciation has been Koreatized. Many of them are based on Chinese and Japanese words that were once written with them. Unlike Japanese and Mainland Chinese, which use simplified characters, Korean characters remain very similar to the traditional ones used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and foreign communities. Since their inception, the hancha have played a role in shaping early writing systems, but subsequent language reforms have reduced their importance. History of occurrence

Chinese characters in the Korean language appeared through contact with China between 108 BC and 313 AD, when the Han Dynasty organized several districts in what is now North Korea. In addition, another major influence on the spread of hancha was the text "One Thousand Classical Symbols", written in many unique hieroglyphs. This close contact with China, combined with the spread of the neighboring country's culture, had a strong influence on the Korean language, as it was the first foreign culture to adopt Chinese words and characters into its own writing system. In addition, the Koryo Empire further promoted the use of hieroglyphs when, in 958, examinations were introduced for civil servants requiring proficiency in Chinese writing and Confucius ' literary classics. Although Korean writing was created by the introduction of hancha and the spread of Chinese literature, they did not properly reflect the syntax and could not be used to write words.

**Phonetic transcription of Imu**

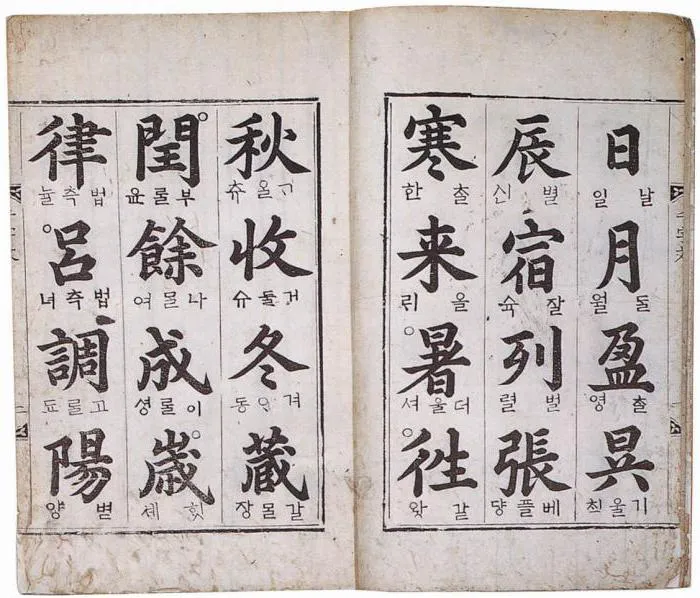

Early writing systems developed to write Korean words using hancha were imu, kugel, and simplified hancha. Imu was a system of transcription based on the meaning or sound of Chinese logograms. In addition, in the imu, there are cases when one character represented several sounds and several hieroglyphs had the same sound. The system was used to write official documents, legal agreements, and personal letters during the Koryo and Joseon dynasties, and was used until 1894, despite not being able to correctly reflect Korean grammar.

Disadvantages of hunch

Although the imu system allowed transcribing Korean words based on their meaning and sound, the Kugel system was developed. She helped to better understand Chinese texts by adding her own grammatical words to sentences. Like the idus, they used the meaning and sound of logograms. Later, the most commonly used hancha for grammatical words were simplified and sometimes merged to create new simplified Korean characters. The main problem of Imu and Kugel was the use of either only the sound without connection with the semantic meaning of the hieroglyph, or only the meaning with a complete rejection of the sound. These early writing systems were replaced by the Korean alphabet and the 1894 Kabo reform, which resulted in the use of a mixture of hancha and hangul to convey the morphology of words. After the end of World War II in 1945, the use of the Korean language was restored, and the governments of North and South Korea began to implement programs to reform it.

Northern version

The policy of language reform in the DPRK was based on communist ideology. North Korea has named its standard "munhwao, "or" cultural language, " in which many Japanese and Chinese loanwords have been replaced with new fictional words. In addition, the government of the DPRK managed to solve the "homophone problem" that existed in Sino-Korean words by simply removing some words with a similar sound from the lexicon. In 1949, the government officially abolished the use of hancha in favor of hangul, but later in 1960 allowed them to be taught, because Kim Il Sung wanted to maintain cultural ties with foreign Koreans and because it was necessary to master the "cultural language", which still contains many borrowings. As a result, 3,000 hancha students study in the DPRK: 1,500 for 6 years of secondary school, 500 for 2 years of technical school, and finally 1,000 for four years of university.

Southern version

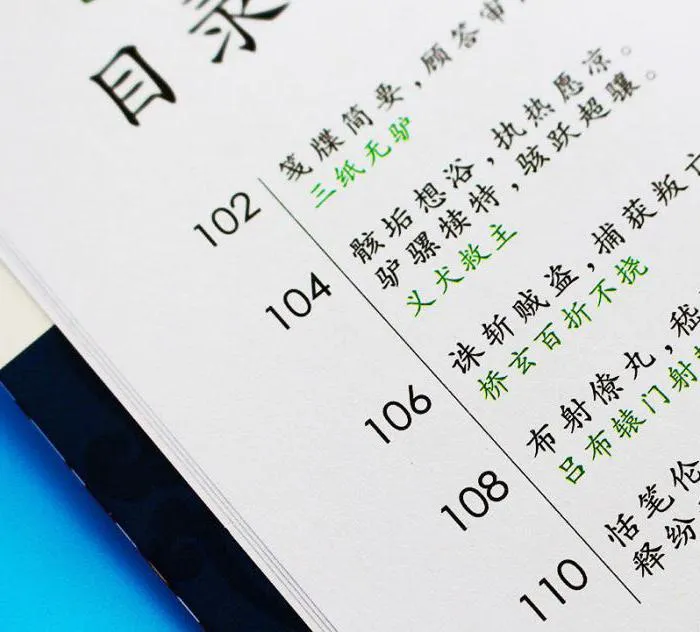

Like the leadership of the North, the South Korean government tried to reform the language, ridding the lexicon of Japanese loanwords and encouraging the use of native words. However, unlike the DPRK, the republic's policy towards Hancha was inconsistent. Between 1948 and 1970, the government attempted to abolish Korean characters, but failed due to the influence of borrowing and pressure from academic institutions. Because of these failed attempts, the Ministry of Education in 1972 allowed the optional study of 1,800 hancha, of which 900 characters are taught in primary school and 900 characters in secondary school. In addition, the Supreme Court in 1991 allowed only 2,854 characters to be used for personal names. The different policies on Hanch show how language reforms can be harmful if they are politically and nationalistically motivated. Despite this, Korean characters continue to be used. Since many loanwords are often consonant, hancha explain the terms, helping to establish the meaning of the words. They are usually placed next to the hangul in parentheses, where they specify personal names, names of places and terms. In addition, thanks to logograms, similar-sounding personal names are distinguished, especially in official documents, where they are written in both scripts. Hancha is used not only to explain the meaning and distinguish homonyms, but also in the names of railways and highways. In this case, the first character is taken from the name of one city and another is added to it to show which cities are connected.

Korean characters and their meaning

Although hancha are still used today, government policies regarding their role in the language have led to long-term problems. First, this has created age restrictions on the literacy of the population, when the older generation has difficulty reading texts in Hangul, and the younger generation is difficult to read mixed texts. It is called the"hangul generation". Secondly, the state's policies have led to a sharp reduction in the use of hancha in the print media, and young people are trying to get rid of Sinoism. This trend is also taking place in the DPRK, where hieroglyphs are no longer used, and their place has been taken by ideologized words of native origin. However, these reforms are becoming a serious problem, as states have replaced words of Chinese origin in different ways (for example, the vertical letter in South Korea is called serossygi compared to neressygi in the DPRK). Finally, recently, the language has seen the spread of English loanwords due to globalization and the large number of South Korean Internet users, which has led to their replacement of words of Chinese origin.T

he future belongs to Hangul

Chinese characters, in the form of hancha, came to Korea at the beginning of the Han dynasty, gradually influenced the Korean language. Although this gave writing, the correct translation of some words and grammar could not be achieved until the Korean Hangul alphabet was developed. After World War II, North and South Korea began to reform the language in an attempt to purge it of Japanese words and historical Chinese loanwords. As a result, the DPRK no longer uses hancha, and the South has changed its policy towards them several times, which has led to a poor command of this writing system by the population. However, both countries managed to replace many words written using Chinese characters with Korean ones, and there is a tendency to increase the use of hangul and words of Korean origin, which is associated with the growth of national identity.***