Source

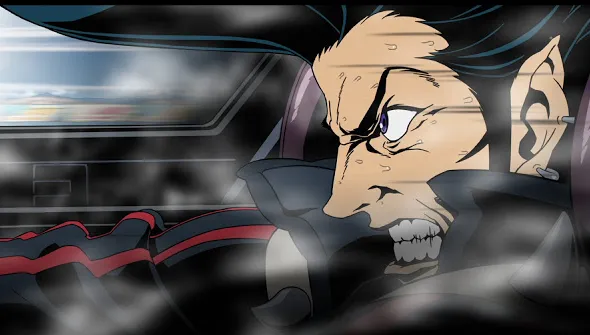

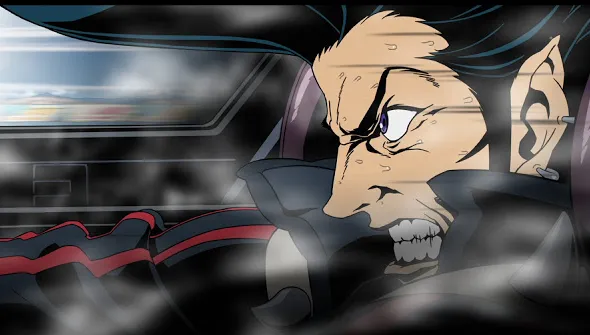

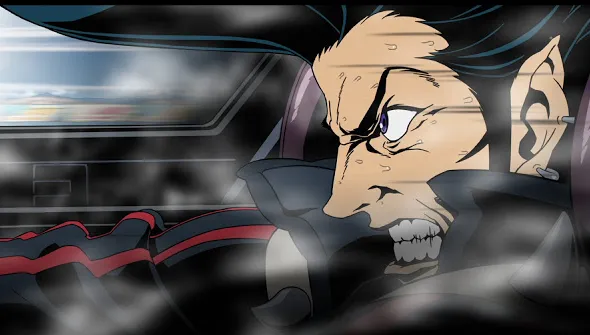

Racing movies usually bore me. They’re too often obsessed with engines, stats, and sweaty machismo. But Redline? It hit me differently. It’s an unapologetic sensory assault, sure—but beneath its chaos, there’s a strange, quiet clarity. Watching it, I wasn’t just tracking the race—I was studying JP, the lanky, pompadoured protagonist who drives like he’s chasing something deeper than just a finish line. That glint in his eye, the almost suicidal push against every limit—it felt less like arrogance and more like the desperate rebellion of a man who refuses to live life at half-speed. I recognized that impulse. Not in the speed, but in the stubborn pursuit of something pure in a world rotted by compromise.

People often talk about this movie like it’s just “style over substance.” They couldn’t be more wrong. Redline masks its emotional gravity in candy-colored absurdity, but underneath it all is a layered look at obsession and identity. JP isn’t trying to win; he’s trying to stay true. He could have everything handed to him—rigged races, easy wins—but he keeps throwing that all away for something harder, something honest. That’s what stuck with me. There’s something deeply psychological about that kind of self-sabotage—this inner compulsion to prove you’re not part of the system, even when it would be so much easier to just play along. It’s not heroism; it’s an identity crisis on wheels.

Source

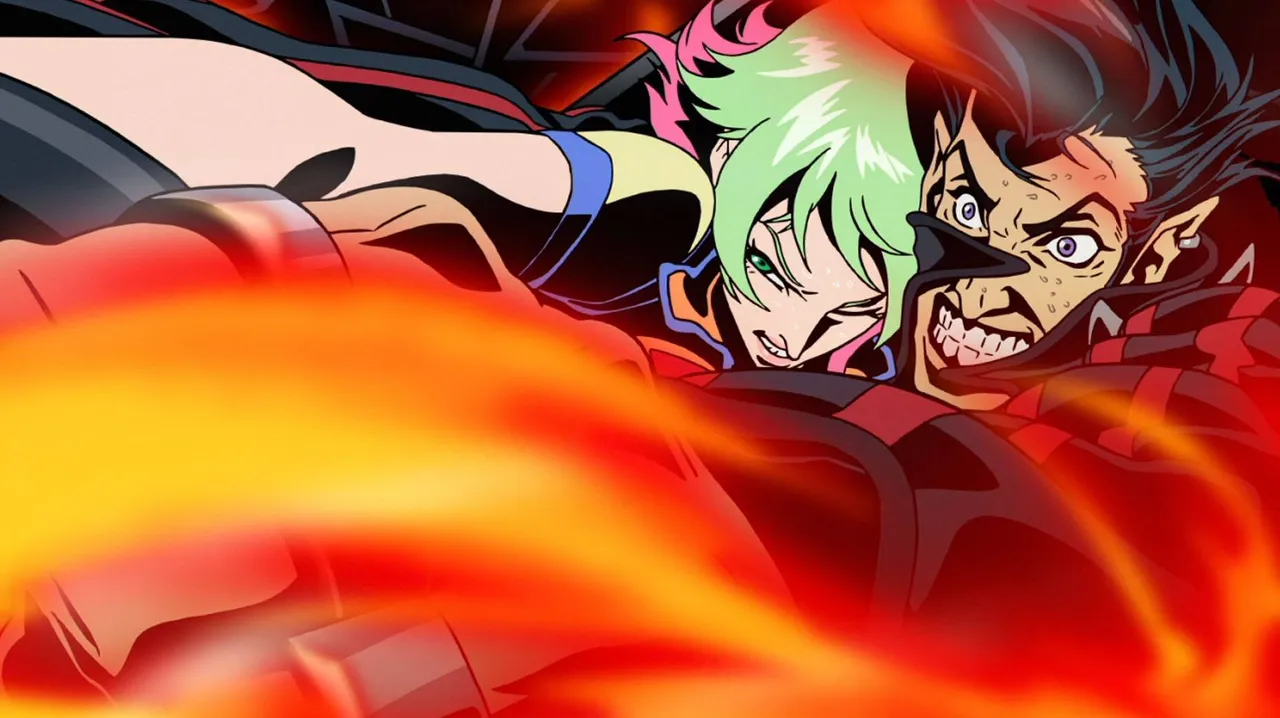

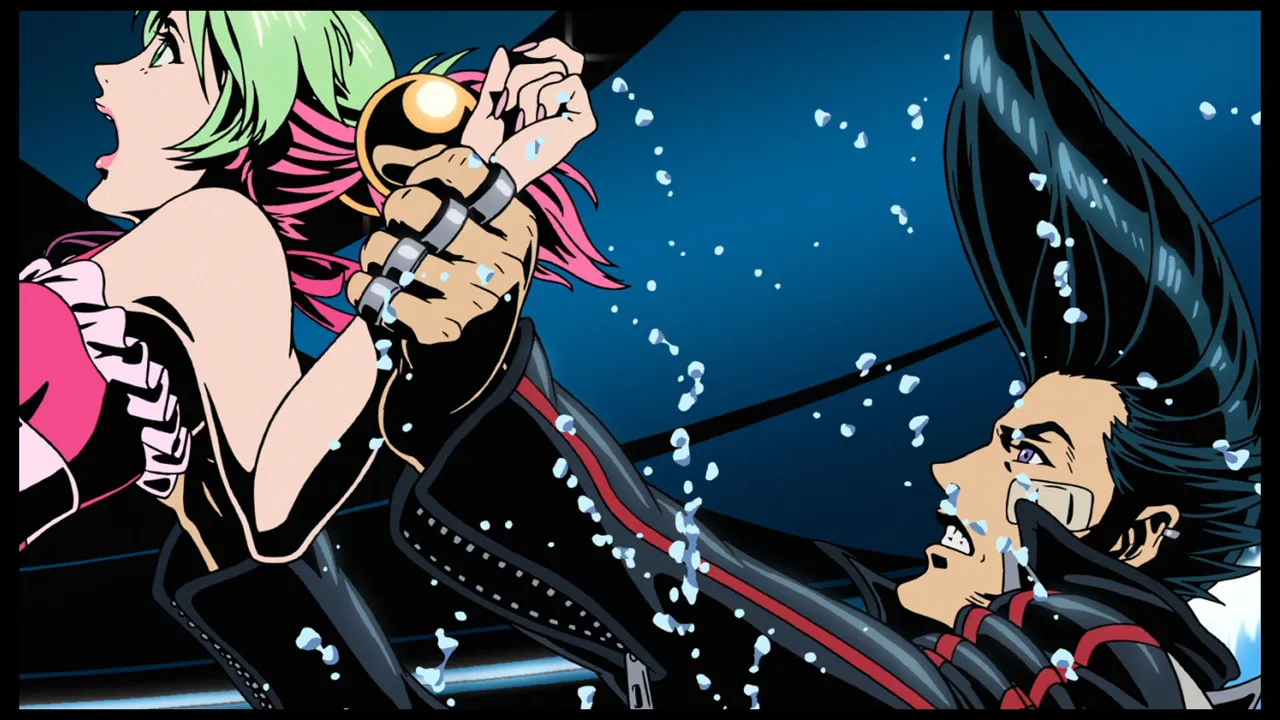

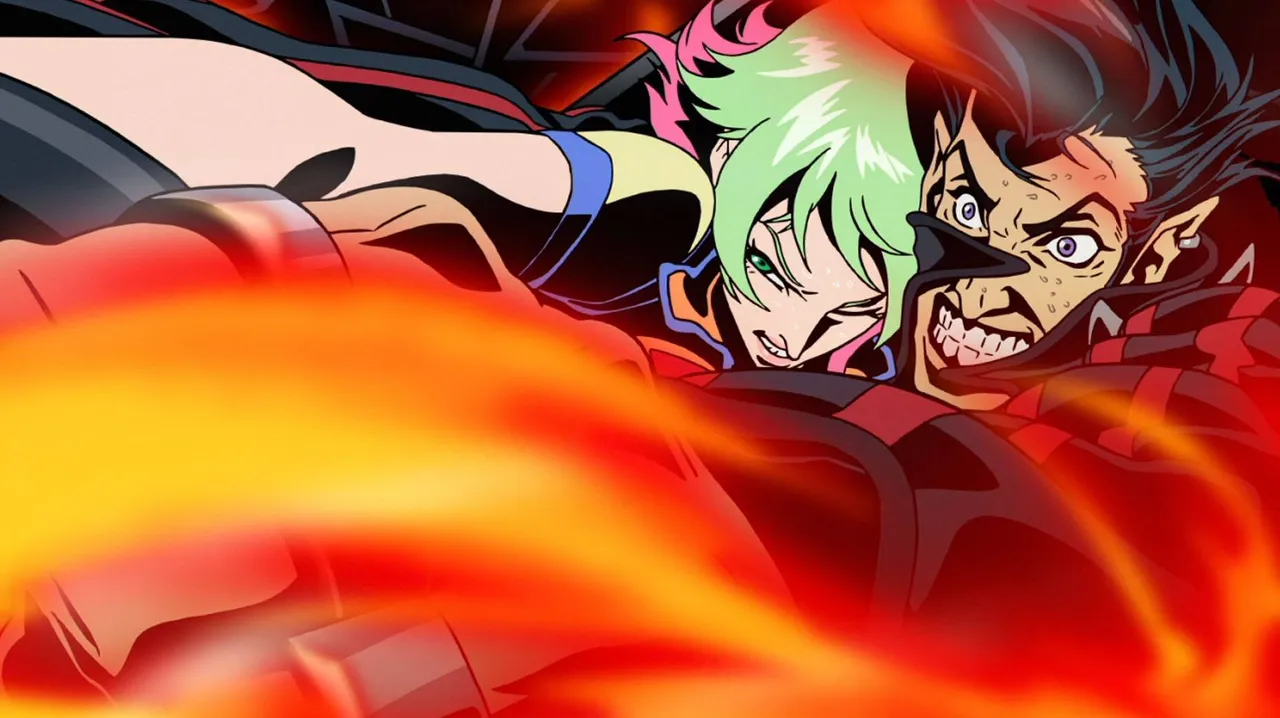

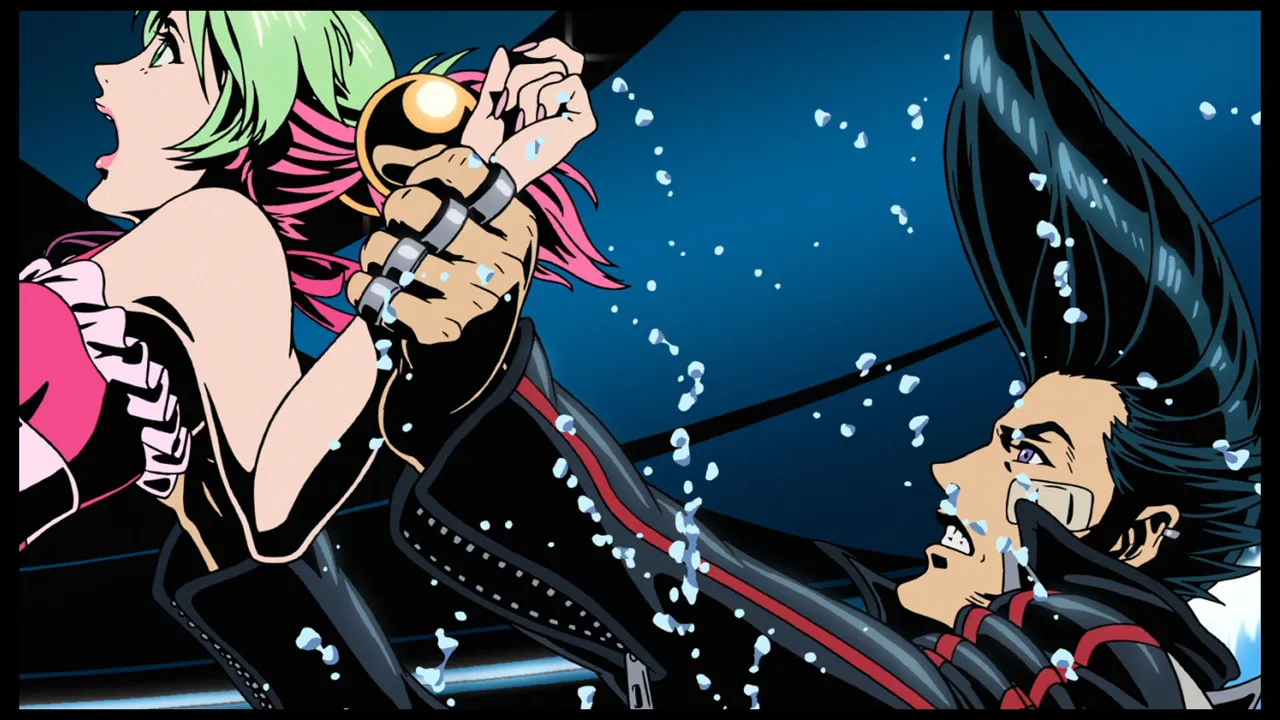

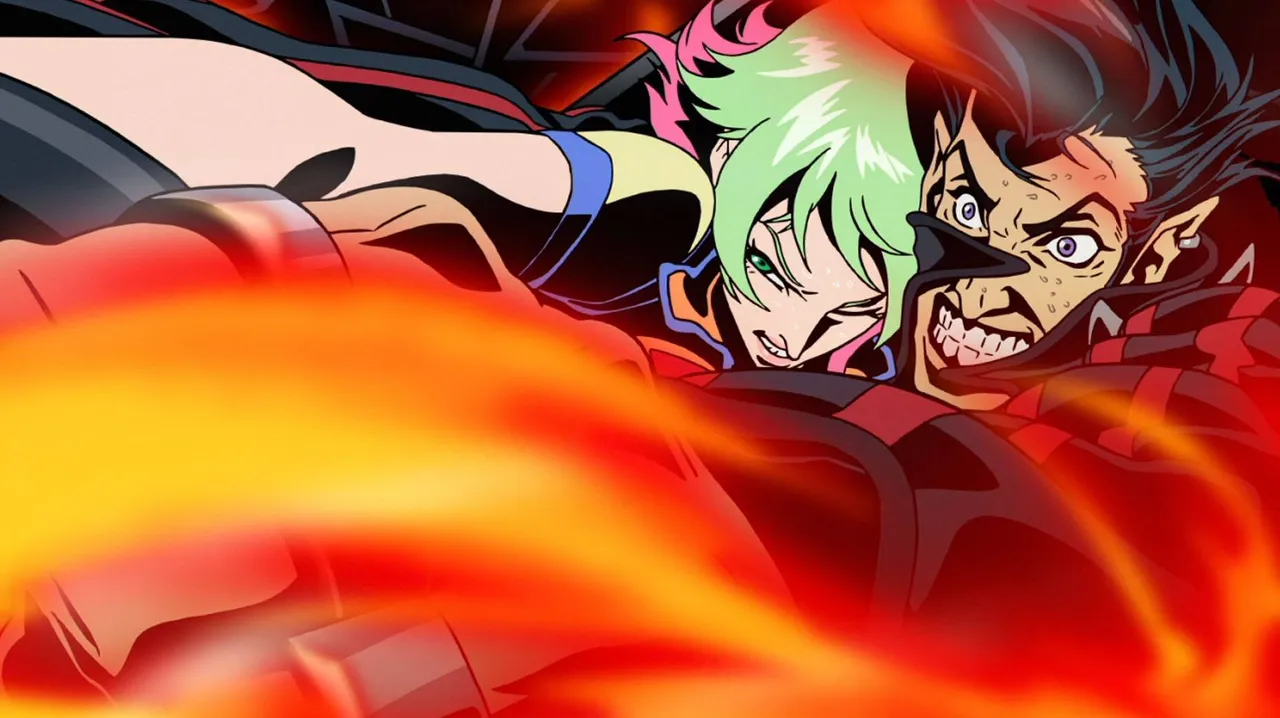

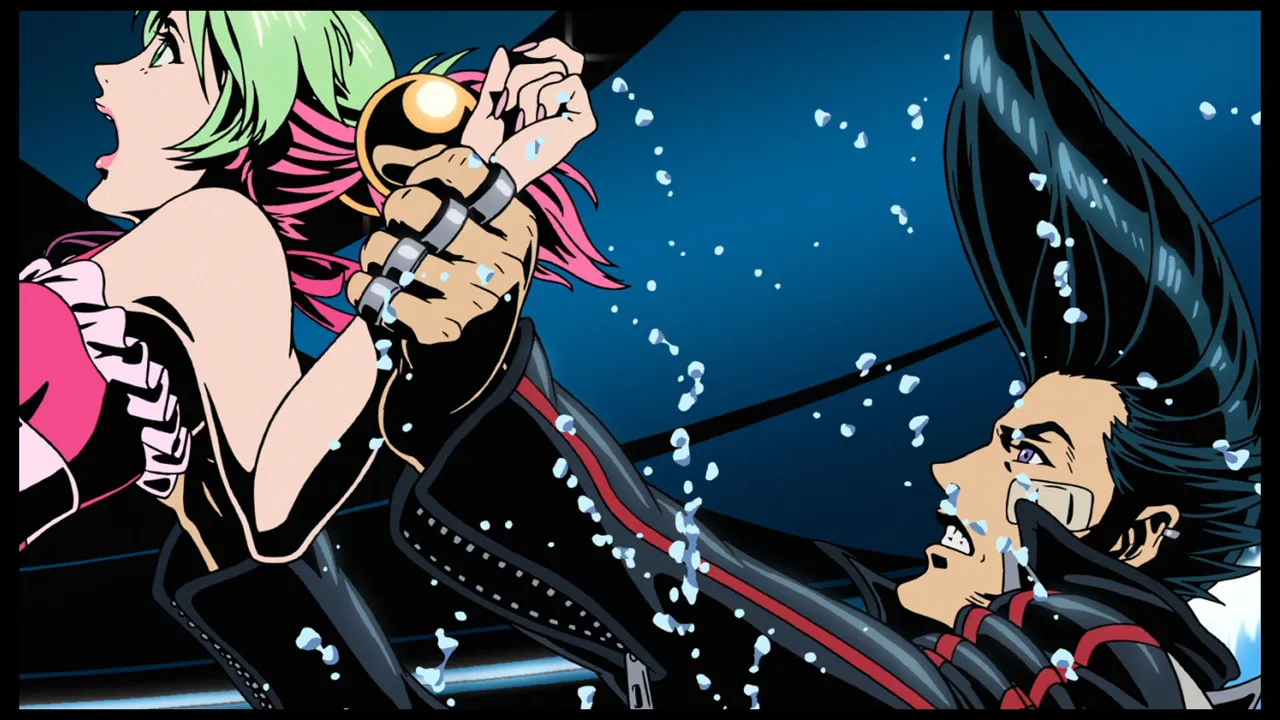

Normally, I’d laugh off the romantic subplot in a movie like this, but with Sonoshee, it works. She’s not a reward, she’s a mirror. Where JP masks his anxiety in bravado, Sonoshee hides hers in aggression. She races like she’s daring someone to stop her. The two of them are orbiting around the same trauma: the need to matter in a world where nobody is watching unless you explode in flames. There’s a moment where they’re midair—cars torn to hell, flames licking the sky—and they look at each other like they finally see themselves. That shot said more than dialogue ever could. The film isn’t asking us to cheer them on—it’s asking if we would risk everything for something that feels real, even if it burns us alive.

Redline is a love letter to excess, but not the kind that’s empty. Every hand-drawn frame screams intention. I caught myself pausing just to study the linework. The frame never settles—it jitters, pulses, breathes. There’s grit in the gloss, which makes the spectacle strangely human. When Funky Boy erupts from the ground or when the racers tear through Roboworld’s military blockades, it’s not just impressive—it’s felt. You can practically hear the animators’ wrists ache. This kind of art isn’t designed to age gracefully—it’s built to scar, like the grease and heat of old racecars that still somehow run. Watching Redline reminded me what animation can do when it refuses to be clean, when it dares to feel alive.

Ultimately, Redline isn’t a movie about a race—it’s a portrait of defiance. It’s what it means to keep doing something stupid and beautiful just because it feels like you. For me, it was a reminder that meaning doesn’t always arrive in neat arcs or tidy character development. Sometimes it screams past at 800 miles an hour, wrapped in chrome and fire, daring you to catch a glimpse before it’s gone. And maybe that’s enough. Maybe, in a world obsessed with control, doing something reckless and honest is the most grounded thing we can do.