Source

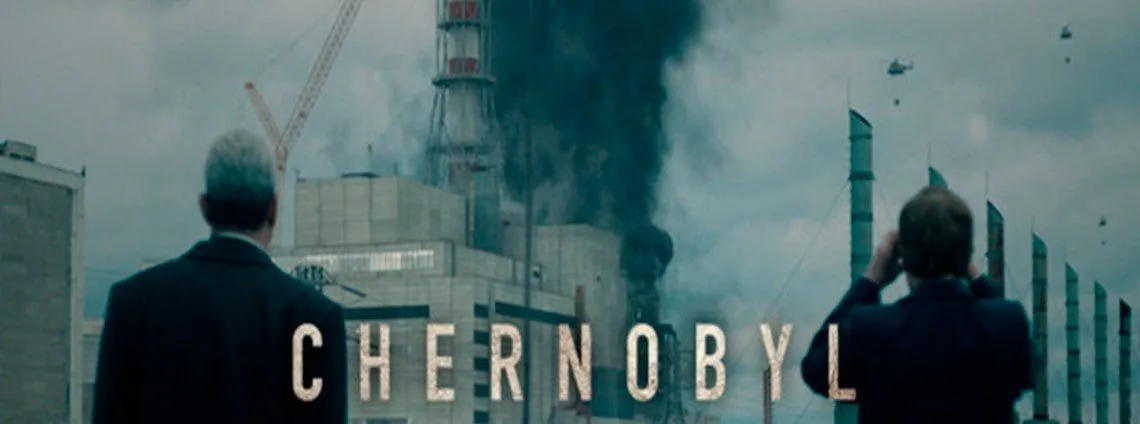

How do you measure the weight of a lie? That’s the question that Chernobyl plants early on, and then lets rot quietly beneath the surface of every scene. It’s not just about an explosion—it’s about the ideological meltdown of a system that depended on obedience more than oxygen. Watching it, I didn’t just see graphite burning or skin dissolving. I saw the Soviet regime’s compulsive need to control truth, to engineer reality even as it crumbled. The silence wasn’t just bureaucratic—it was existential. You get the sense that everyone is pretending not to die, just to keep the illusion alive.

Just as striking is how HBO turns radiation—something invisible, abstract, almost mystical—into something you can feel crawling on your skin. The visual design doesn’t just depict suffering; it manufactures dread in every frame. The color grading is desaturated almost to death, as if the palette itself is sick. Faces blur under fluorescent lighting, hallways feel endless, and every frame seems soaked in contamination. There’s no safety in shadows or light, just a slow, visual suffocation. The camera doesn’t scream—it watches, quietly, like the state. I couldn’t help but feel that the real horror was not what the eye could see, but what the system refused to.

Source

Lying at the heart of all this is the psychological disfigurement of people forced to live in denial. Not personal denial—political. Emotional. Cultural. You see it in the scientists, the politicians, the workers, even the wives of the dying. There’s a kind of spiritual radiation poisoning happening here, where every person’s sense of reality is corroded by the Party’s insistence that nothing’s wrong. The trauma isn’t only caused by the event; it’s sustained by the ideology. By the need to believe in infallibility. And that gets under your skin in ways I wasn’t ready for.

People often talk about heroes in stories like these, but I didn’t find any. I found people clawing at scraps of decency in a system that punishes honesty. Legasov, in particular, isn’t framed as a savior—he’s framed as a man whose mind is collapsing under the pressure of knowing the truth and watching the world reward those who deny it. There’s no music swelling, no moral clarity. Just fatigue. Desperation. And a haunting question: how long can a person carry the truth before it crushes them? The genius of the series is that it doesn’t answer that. It just lets you sit with it.

Ultimately, Chernobyl didn’t devastate me because of the disaster. It devastated me because it showed how easily reality can be rewritten, not just by force, but by fear. By loyalty. By silence. That’s what lingers after the credits: the knowledge that totalitarianism isn’t just a system—it’s a virus that rewrites memory, erases pain, and paints obedience as virtue. Watching it felt like inhaling something I couldn’t cough out. Not because it was graphic. But because it was honest.

Source