Spoilers ahoy - but it's a documentary, can you really spoil that?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seaspiracy

Synopsis of the film - Aziz Tabrizi and his wife Lucy fly all around the world to better understand what is happening in the world's oceans. The film starts with them heading to the Taiji dolphin hunt, where they elude authorities (and maybe Yakuza?) to film dolphins being slaughtered from the cliffs above the bay. Initially they're under the impression that the purpose of the dolphin hunt is to supply sea parks with trained animals, but quickly discover that in Taiji, fishermen are killing 10x more dolphins than they capture. Pursuing the matter further, they discover another rationale at play - dolphins are being blamed for decreasing fish harvests, and so are being exterminated under the same rationale that settlers decimated sea otter populations in the pacific northwest over a century ago.

The realization over collapsing fisheries off the coast of Japan opens another door that the Tabrizis go through - that which explores the role of commercial fishing in the destruction of the planet's oceanic ecosystem, the largest and most important stabilizing force in the biosphere.

Without sufficient fish in the sea, the logic unfolds, the whole system collapses. As humans eat the big fish, the smaller fish are freed from predation. They bloom, overgrow, and bust - driving the collapse of the food chain all the way down to the smallest creatures. The increase in carbon dioxide levels is given as the primary reason for the decreases in ocean health, but Seaspiracy presents an alternative hypothesis - what if the act of commercial fishing itself is what is causing the collapse of the ocean? More importantly, what if the only possible alternative is to stop eating fish altogether?

Analysis: The movie highlights the hypocrisy inherent in the mechanisms by which we soothe ourselves into thinking we're responsible consumers. The Marine Stewardship Council, the organization that sells sustainable fishing stamps for consumer goods has few observers in the field, and makes the majority of its money off of certifying fish products as sustainable. One hand washes another, and we all nod along willingly, because buying something "certified" makes us believe that it's possible to continue along exactly as we have for millenia.

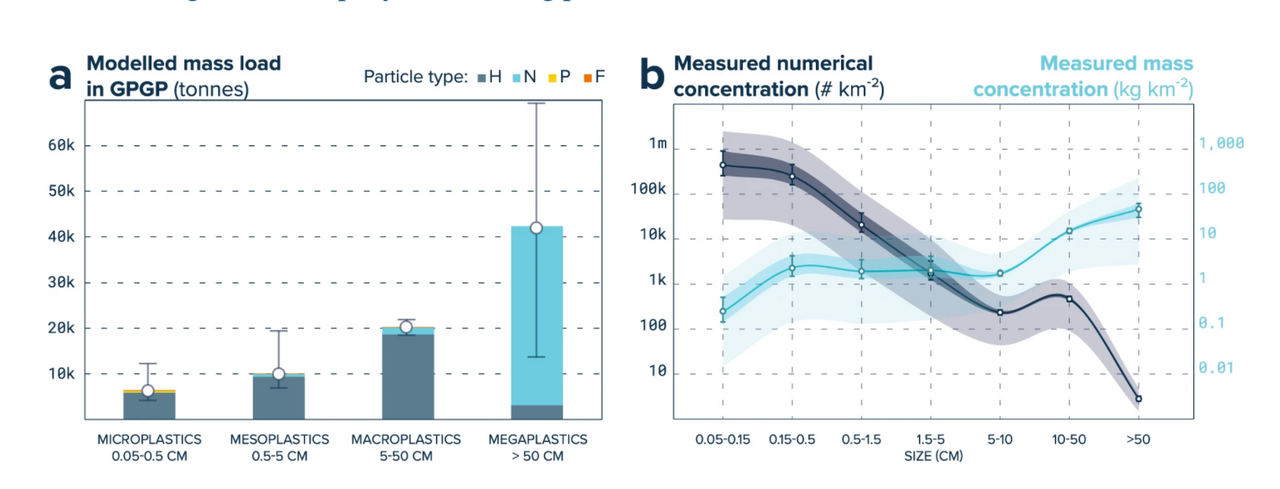

It was shocking to see the movie on Netflix - but it suggests the overton window is slowly shifting. Tabrizi points out in the movie that previous campaigns - like banning plastic straws - were simply greenwashing the catastrophe of the oceans. He cites a statistic to this end - the majority of debris in the great pacific garbage patch (46%) is fishing lines and buoys, while only 0.03% comes from plastic straws. He attributes this to campagin sponsorship - some of the largest campaigns were run by Unilever, the world's largest fish buyer at the time.

What doesn't support the shifting overton window is the New York Times review of the film, which addresses nothing of substance. It simply points out that Tabrizi asked some leading questions to get his juicy quotes. Perhaps it's a difficult pill to swallow when the paper was more than happy to print articles about the urgency of banning plastic straws, but has yet to become the first paper on record to recommend not eating fish as the best thing one can do for the planet.