We debunk the myth of the ruble as an antagonist of the dollar

In this article we will deal with the fanciful reading that many social networks are spreading about the ruble, the Russian national currency.

The unexpected show of strength that the ruble is giving during the Russian-Ukrainian conflict is an indisputable fact, but it is interpreted by some as the beginning of the advent of a strong ruble and the beginning of the end of the supremacy of the dollar.

This post is going to be a little longer than usual but it didn't feel right to split it into multiple parts.

Premise

Just before Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, it took 84 rubles to buy 1 US dollar.

After the invasion, the exchange rate began to fall, until the low of March 7, when it took 131.2 rubles to buy 1 US dollar (we are talking about a significant drop of about 36%).

To everyone's surprise, at some point the ruble rose again, returning exactly where it was before February 24.

The phenomenon occurred in the same period in which Putin had declared to demand payments in rubles for the purchase of gas and oil from Europeans, as well as to set a price for the purchase of gold.

Hence the unleashing on the net of hundreds of posts and articles on the advent of a strong ruble linked to raw materials and gold and the end of the supremacy of the dollar as a global currency.

We will devote a separate article to the question of the link between rubles and gold.

For now, I will limit myself to dispelling the myths that are proliferating about the ruble and the dollar, trying to give an accurate view of the real situation of these two currencies.

The ruble as the new global refuge currency?

The first step to see clearly in this matter is to understand well the meaning of Putin's decision to have oil purchased in rubles.

What will really happen when European country X has to buy oil from Russia according to the new directives outlined by Putin?

It is a three-step procedure:

To get the rubles needed to buy oil, country X sells euros to the Russian central bank.

The rubles thus received are immediately sent back to Russia by country X in exchange for their counter value in oil.

The Russian central bank is left with sums in Euro equal to the equivalent of the oil sold.

Therefore, at the end of the sale, given a certain value Y that is constant throughout the transaction:

-Country X finds itself with the countervalue of Y in oil.

-the Russian central bank gets the equivalent of Y in Euros

-the oil supplier company receives the equivalent value of Y in rubles.

This new method of selling Russian oil therefore does not change the strength of the ruble as a store of value compared to other currencies. If anything, it changes the use of the ruble as a trade currency.

To counteract the strength of the dollar as a world reserve currency, the ruble would have to start accumulating in the vaults of some western central bank, as happens precisely with the dollar.

But this is not the case, because in the trade we have seen, the euro-ruble exchange is done instantly and does not imply an accumulation, even if for a limited time, of rubles by country X.

Moreover, in this purchase and sale, it is the Russian central bank that accumulates euros; and it accumulates exactly the same amount it would have accumulated in the previous type of purchase and sale, that is, when country X, before the war, directly bought the necessary oil in euros.

Russia therefore accumulates euros, not rubles, as a reserve currency and with these euros it will buy, perhaps in China, all those goods that are barred to it by sanctions.

The Russian decision to force Europeans to exchange euros and roubles for the purchase of oil does not therefore serve to impose the rouble as a reserve currency.

If anything, it is a way of supplying itself with euros despite sanctions. And to be able to buy with these euros some goods that would be difficult to find in rubles or yuan.

From the monetary point of view, therefore, Putin's move certainly creates a demand for rubles as an exchange currency, not as a reserve currency.

And for such a measure to be effective, it is necessary for sanctions to be truly worthless.

Fortunately for Russia, sanctions in the contemporary era are useless, because the world is too interconnected.

Here are some examples:

-Europe continues to import oil, gas, food, fertilizer and all the metals it needs from Russia or Ukraine.

-All French companies on Russian soil continue their operations.

-Imports of materials needed by Russian industries are possible in euros, yuan or directly in rubles, depending on the country of origin.

It is these activities and exchanges made in defiance of sanctions that make possible the flow of rubles promoted by Putin with his decision to exchange rubles for euros in gas and oil transactions with Europeans.

If the world had really stopped with Biden's sanctions, this would never have been possible.

So, in summary, the rise of the ruble is due to the fact that Putin has reinvigorated the use of this currency in trade and especially the fact that this trade, despite sanctions, is stronger than ever.

Let's now take a look at the dollar's status as a global reserve currency.

Has anything changed since the war began?

Is dollar supremacy at risk?

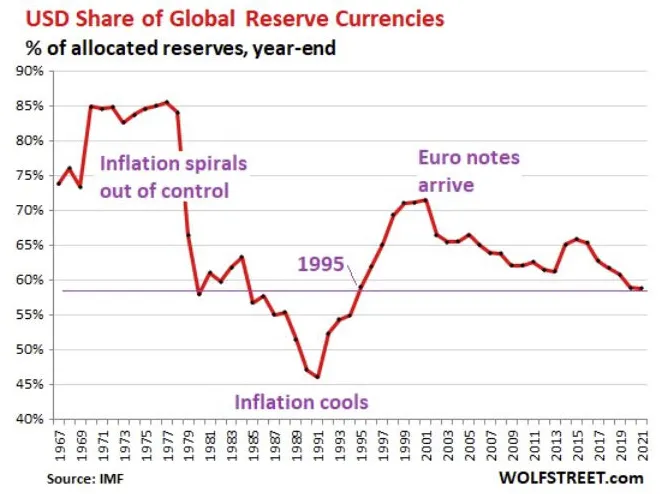

Over the past two decades, USD exchange rates have had relatively little impact on the U.S. dollar's share of global reserve currencies.

Most of the long-term decline in the dollar share is due to central banks' diversification away from dollar-denominated holdings. Basically, since banks have started to accumulate euros as well as dollars....

We see it in this chart:

As you can see, the dollar's descent since the 2000s began because of the creation of the euro.

Lately, the chart doesn't record any particular change in the range between 70% and 58% (as a percentage of reserves compared to global currencies) within which the dollar has fluctuated from '95 to the present.

Certainly, since 2015 a descent towards the lower part of this range has begun.

So I am not arguing that, in the long run, the descent of the dollar as a global reserve is possible.

I am arguing about the overly simplistic cause and effect relationship between what happens today and the prospects of this gradual process.

In fact, we have to consider that the permanence or not of the dollar (or other currency) as a reserve of value is not only a matter of quantity, but also of speed.

Let me explain further.

It is not only the quantity of dollars accumulated by central banks that is important, but also the speed with which the entry and exit of dollars in these banks takes place.

Central banks around the world are very careful to put the brakes on all movements in and out of dollars from their vaults.

This speed regulation is possible because even central bank reserves denominated in other currencies are eventually priced in dollars.

For example, if the Japanese central bank has government securities in euros, the value of those assets on the bank's official balance sheet is priced in dollars, not euros.

So the value of euro securities held by the Bank of Japan is affected not only by the euro-yen exchange rate, but always by the euro-dollar exchange rate as well.

This constant need for the dollar exchange rate even for assets denominated in other currencies allows for the exceptional stability of the dollar as a foreign exchange reserve, beyond exchange rate fluctuations.

No one would start accumulating a currency if it was completely unpredictable in the exchange rate.

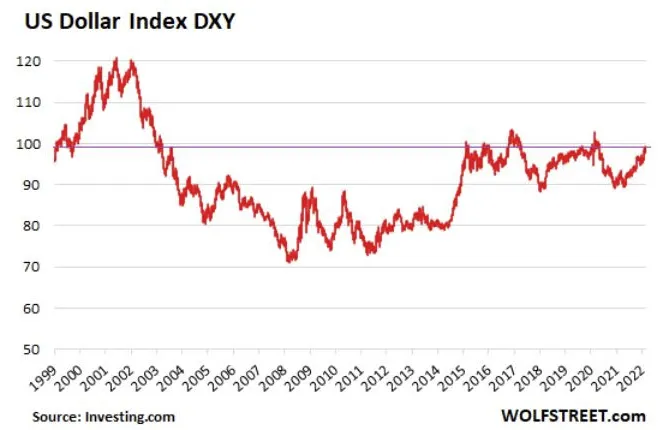

In fact, the exchange rates of the world's major currency pairs, although volatile from month to month, have remained stable against the dollar for the past 23 years.

It is therefore not surprising that central banks choose the dollar as their reserve....

The Dollar Index (DXY) chart, which replicates the dollar against the euro, yen, British pound, Canadian dollar, Swedish krona and Swiss franc, shows this intuitively:

At the time of writing, the DXY index closed at 98.57, virtually unchanged from its 1999 and 2000 levels, despite the dizzying swings in between due to the war.

So, those who are waiting for the collapse of the dollar, or the collapse of the euro or the yen, will have to be very patient, because the central banks, including the Russian and Chinese ones, are still very careful to calibrate well the balance of DXY, even during this war...

In the end, the only way for a country wishing to usurp the hegemony of the dollar to break this balance in the short to medium term would be to win a war with the rest of the world, exactly as the US did in WWII.

But beyond rare and extreme phenomena like these, the advent of another world currency on the dollar is a matter of decades.

Just to be clear, the rise of the ruble we are talking about, seen in a broad time perspective, is very little (the "v" produced by the chart below right) and certainly does not justify the bombastic announcements of conspirators on the imminent collapse of the dollar:

To sum up: for the moment, the ruble is defending itself well, because it has managed to recover the ground lost as an exchange currency in commercial transactions.

Instead, for the advent of a strong ruble, perhaps pegged to gold or oil, let's talk about it again in a decade or so...

Thanks for reading.