I'm a commaholic.

I use too many commas and I want to cut back.

The goal

One goal, or rule, I'm setting for myself for 2021 is to cut back on commas.

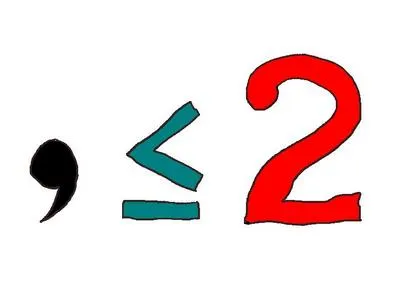

Here's my new rule:

You will use "no more than two commas per sentence.^"

There is an exception^: if the sentence is a list, then it's okay to go over by separating items with a comma. For instance: After work today, I stopped and picked up rutabaga, potatoes, onions, and red wine. There are four commas, but the little ^ exception says that I'm okay.

I guess this pledge goes along with other recent post about writing - "How to write properly." In it, I included the "recipe" for writing.

The problem

My problem has been that I include too many thoughts in my sentences. Maybe an English teacher would name them as clauses. I don't know. I'm not that good in grammar and syntax and such.

There is evidence that shorter sentences yield greater comprehension. I don't know where that evidence is, and I'm not interested in looking it up right now. But, I heard it a lot, so it must be true. Right? And, besides, you can find evidence for anything you want to "prove" nowadays. Right? And third, any time somebody starts off a sentence with, "Well, research shows that...", my skeptical brain starts to shut down. Starting your sentence with that seems preachy and like you're trying to sound smart.

The odd thing is, I've usually heard the "shorter sentences increase comprehension" argument from pastors. There's a lot of debate among theologians and parishioners as to what's a good Bible translation. There's a slogan, "If it ain't King James, it ain't Bible." That might be a bumper sticker too.

A second odd thing is that it was a Bible devotion that I recently read that prompted me to make the two-comma rule and to write this. It had been written by a pastor in a denomination that is concerned about accuracy in translation. The sentence held five commas, as I recall. I had to read it, re-read, then re-re read it. Still, I'm not sure I entirely got it. To be better, the sentence could simply have been broken into two. Shorter sentences increase comprehension.

Most people I hear agree that the 1611 King James version is, indeed, great. It's accurate and beautiful. Scholars took the original words in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek and translated the words into English. This is not as easy as a literal word-for-word translation, though. The context matters. The historical time period matters. Culture matters. Anyway, the key is that a translation uses the original language.

The problem, today, comes down to comprehension. People today do not speak the same the as Shakespearean English of King James. The fear is that, though a solid translation, modern comprehension may be lost.

By contrast, other "Bibles" like "The Message" do not look at the original languages, then translate. They look at the English translation, then try to re-convey the meaning that they perceive. I would not be able to translate the Bible because I cannot understand Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek. I could write a paraphrase, by looking an English version and then re-wording it into my own flavor. (I'm definitely not going to do that.)

An exercise

Let's do a real-time translation vs. paraphrase exercise.

I'll translate, "Shorter sentences produce greater comprehension."

Las oraciones más cortas producen una mayor comprensión.

This is a translation, thanks to Google. It took the original English words and translated them to Spanish.

I'll paraphrase, "Shorter sentences produce greater comprehension."

- Paraphrase 1 - By keeping sentences short, understanding is improved.

- Paraphrase 2 - Shorter is better.

- Paraphrase 3 - You know what you're trying to say. Therefore, it's easy to jump to a second thought within your main thought. However, your reader does not know what you're trying to say. Jumping to a second thought only confuses him or her. Stick to one thought per sentence.

- Paraphrase 4 - People are dumb. You gotta dumb it down to their level. Otherwise, you lost 'em.

- Paraphrase 5 - tldr;

These five paraphrases are wildly different. But, each did not refer to the original words. Instead, they referred to the original meaning (as perceived), then re-wrote things in attempt to convey that perceived meaning.

My comma problem started in college

As a young man I got on a Hemingway kick and read pretty much everything he wrote in a very short period. Of course, Hemingway is a fantastic writer. But, he has a unique, staccato, machine gun ratta-tatta-tat rhythm to his words. His sentences read as a bit of a sing-song. For instance, The Old Man and the Sea begins, "He was an old man who fished alone in a skiff in the Gulf Stream and he had gone eighty four days now without taking a fish." To me, I hear a rhythmic beat as I read.

He also had a habit of writing very long sentences glued together by the word "and". For instance, from the end of the first paragraph of A Farewell to Arms, "The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves."

That's one long sentence. I'm pretty sure an English teacher would label it a "run on" and slice it up with her red pen. Hemingway'd get a "D". But, after I'd read that sentence, I was drawn in. As a whirlpool of water sucks a small fly resting on the water's surface down into the depths, I was pulled into that book after those words. (And it's likely still my favorite novel.)

However, I think my commaholic problem was beginning. I believe my tendency is to replace "and" with commas. Whereas Hemingway offset thoughts with "and", I use the comma.

In psychology, there are concepts called the "critical period" and "imprinting". The critical period is the time in development when you learn something, else it's not learned. And imprinting is stamping whatever you learned so that it's not un-learned later. For instance, ducklings enter a "that's mommy" critical period shortly after hatching. The research shows (catch that?) that ducklings will imprint the concept of "mommy" onto anything moving during the critical period. You can trick a ducking into thinking a chicken is mommy. A puppet duck is mommy. A person is mommy. Anything that moves. Poor little duckies.

With people, we learn to speak the language that we hear as toddlers. We pick up the accent and inflection of that language. And, we do it effortlessly and naturally. When that critical period ends, we can still learn a new language. And adult can learn a new language, with effort. Also, an adult who learns a new language will never get the accent 100% correct. In another way, the adult will never lose the accent of his or her original language. It's imprinted.

Maybe I was in a "sentence structure" critical period in college. And maybe all that Hemingway stuff I read messed me up. It imprinted something in the language-syntax portion of my squirrel brain. (Does a squirrel have a Wernicke's area?) Instead of run-on sentences with lots of "ands", I consistently break sentences apart with lots of commas. And, maybe all that reading imprinted A Farewell to Arms as my favorite novel.

But, no more to the comma problem!

This somehow became long. And, since research shows that shorter sentences increase comprehension:

tldr;

No more than two commas per sentence!

If you’re new to Hive, consider signing up. The #1 benefit...YOU own your content and YOU earn the rewards your that content generates. Consider using my referral link below if you join.

Learn more or get your free account here.

:)