Can people earn a living by blogging on Hive, and why should we care?

In this post I aim to discuss the potential for authors to 'earn a living' on Hive. What does it mean to "earn a living" in the first place? What does it take to earn a living? How many people are doing that already? And finally, why the potential of authors to earn a living matters for those who are invested in Hive.

4 months ago I wrote a post about how many Venezuelan authors were already earning more than the minimum wage in the country, merely by blogging on Hive. While the title of that post was true, the connotation for most readers may have been that earning such an amount meant covering the basic costs of life in the country, at least for a modest living standard. Unfortunately things are more complicated than that, and after more discussion with Venezuelans here on Hive, it was clear that the number of authors who could actually cover their life costs with their Hive author rewards was a much smaller group. Today I will revisit the topic with a particular focus on Venezuela and Cuba.

What does it mean to "earn a living"?

In the most basic sense, earning a living means that you are earning sufficient income that it can cover the costs of your lifestyle. However standards of life can vary quite wildly across the world and between social classes within a national community. Here are some metrics by which we can potentially determine if someone is "earning a living" on Hive.

1. Salary Replacement

We can potentially say that someone is earning a living on Hive if the earnings they make here are enough that it brings in at least as much income as a regular full time job in the home country. This is probably the simplest metric, with the most available statistical data. It will also be valid for most of the world. However the very countries where Hive arguably has the most potential have dysfunctional economic systems, and those who get nothing more than an ordinary salary may be struggling, failing to meet basic needs. In Venezuela or Cuba, you have to do more than earn your salary to get by, you need other means. Those means may be remittances from relatives who have emigrated to a more functional economy, or it may be illicit earnings from corruption or petty crime that people have no choice but to engage in.

Salary replacement may be the easiest metric to meet, it will include those who can replace regular employment with Hive blogging, but they still may not truly be covering their life's costs.

2. Comparative Cost of Living

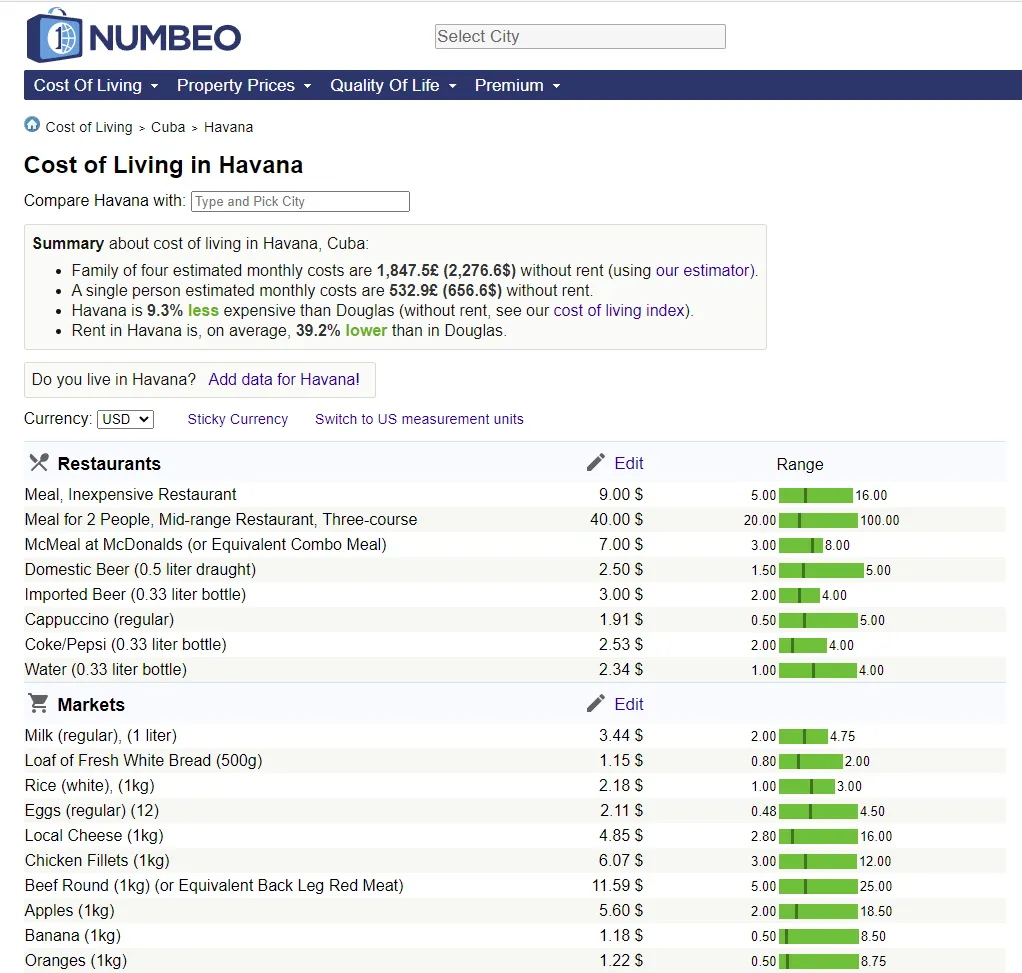

Using sites like numbeo.com and others, one can compare a standardized cost of living between different regions. Digital nomads and ex-pats will often use such sites to evaluate what their cost of living might be if they decide to spend a few months or years abroad.

The advantage of these sites is that they provide a relatively standardized, like for like comparison. That is also the main problem though - lifestyles are not standard across countries. You can potentially live very cheaply in a foreign country, if you adapt your lifestyle to what is locally available. Transplanting a western/developed lifestyle to a lower cost country may not work out as expected - if you want the same availability of the kinds of food you're used to, consumer goods, toiletries, transport options etc. those things could actually cost substantially more than they did at home. These sites have other problems as well - the data is usually crowdsourced from individuals who voluntarily submit to the site, making it self selected, and they have limited ability to verify for accuracy. More accurate data can often be found from national statistical bodies who monitor inflation (eg. The Bureau of Labor Statistics in the US), but the baskets of goods are not standardized across countries nor are they conveniently available for comparisons.

In the end, sites like numbeo.com can be a useful tool for getting a rough idea of what life might cost as an ex-pat, it likely represents an inflated cost compared to the standard of life that is normal in the region.

3. Local Cost of Living

As mentioned above, National Statistics Offices usually maintain an index of goods and services that represent the typical expenses for a family or individual living in the country. These indexes contribute to the Consumer Price Index that they publish, and are based on surveys typically performed yearly or quarterly. Usually these are a more accurate representation of a typical local lifestyle than what might be found on numbeo.com or similar.

Unfortunately again, the countries we are most interested in often don't have very reliable national statistical bodies. In more authoritarian countries, publishing accurate but negative data can be problematic for your career, so the tendency is for statistical data to be skewed to make for positive outcomes. Venezuelan government statistics are notoriously unreliable, and Cuba seems to have similar problems with using outdated models in their measurement of CPI.

In the absence of reliable statistical data, an alternative is to perform our own survey. Using a "wisdom of the crowds" method by asking several individuals to estimate, and then taking the median answer - as long as people provide their answers independently - the result can be surprisingly accurate. There are weaknesses to this method, but it may be the best available option when lacking reliable statistics.

Final measurements

Using all the above methods, this is what I find are the costs of living by each metric. As mentioned above, each one should be treated as having a high margin for error. All numbers in USD.

| Metric | Venezuela | Cuba |

|---|---|---|

| Salary Replacement | 175 | 30 |

| Numbeo | 596.70 | 656.10 |

| Surveyed Median | 275 | 60 |

We can see above that the comparative cost of living (Numbeo) metric is the hardest highest standard to meet in both countries, and salary replacement is the easiest to meet. Both are likely unrealistic, and I expect the real local cost of living to be closer to the surveyed median, which we can see falls in the middle for both Venezuela and Cuba. It is also worth noting that Numbeo has Venezuela as a slightly cheaper place to live than Cuba, but the other methods find Venezuela substantially more expensive to live in for locals.

Hive Authors Earning a Living

Now that we have some methods by which to judge, we can determine how many Venezuelan and Cuban authors on Hive are actually making a living in author rewards already. I used two queries on @hivesql to find Venezuelan and Cuban authors and their author rewards in February. For Venezuelans I selected all users with either "Venezuela", "Caracas", "Cumaná", "Maracay" or "Venezolana" as their location in their profile data. For Cubans I selected all users with either "Cuba", "Havana" or "Habana" in the same.

Of course it must be remembered that this is a subset, from previous analyses, the majority of users do not include their location in their profile.

| Measurement | Venezuela | Cuba |

|---|---|---|

| Total Users Found | 1224 | 79 |

| Users that earned at least $0.01 | 998 | 69 |

| ^ As a Percent | 82% | 87% |

| Users that earned at least $1 | 816 | 53 |

| ^ As a Percent | 67% | 67% |

| Users that earned at least $100 | 30 | 0 |

| ^ As a Percent | 2.5% | 0% |

| Users that earned at least Salary Replacement | 3 | 10 |

| ^ As a Percent | 0.2% | 12.6% |

| Users that earned at least the surveyed median cost of living | 1 | 0 |

| Users that earned at least the Numbeo Comparative Cost of Living | 0 | 0 |

Conclusions

Depending on how you measure the cost of living, either a small number of people or an extremely small number of people are earning a living through author rewards alone on Hive, in economically troubled but relatively low cost of living countries such as Venezuela and Cuba.

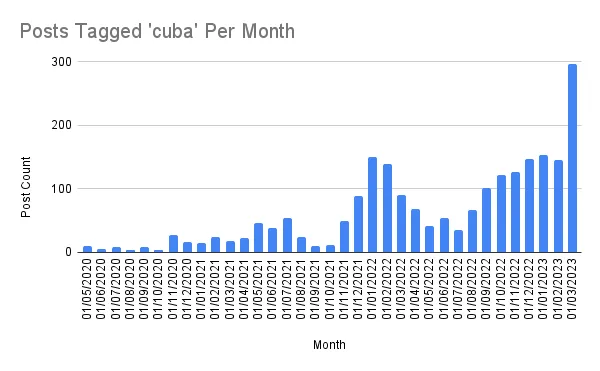

I want to make a particular note that although no Cuban users match the median cost of living in author rewards yet, several are extremely close. Also, the Venezuelan community has been established on Hive since before the 2020 fork from Steem, where the Cuban community is something that has emerged on Hive only recently (see chart below). As such, the potential to earn a living on Hive is likely higher for Cubans than for Venezuelans due to differences in local standard of living and costs associated.

These earnings also represent what is possible during the depths of a bear market for Hive.

Why it matters for Hive Stakeholders

The ultimate goal for Hive is to build an economic network, in which people have the freedom and ability to transfer money easily, without censorship from states, institutions or anyone else. For this to happen, the network effect must be built, and that means real people using Hive and HBD for real commercial purposes. The vast majority of value transfers exist between people who know eachother or whom meet in real life, to meet the basic needs of life. Crucially, Hive only needs to become established in at least one geographic region to form a robust, self contained economy. Digital economies that are not embedded in people's day to day lives are not as likely to be as robust as a circular economy that exists in a local region, because when you only use a token for one thing, it is much easier to replace it with something else. From such a robust base, it is more likely to expand outwards.

The network effects that Hive has developed in Venezuela have proven to be robust, in that they have continued and survived through multiple bear market cycles. In the current bear market, it is not growing, but it has demonstrated that resilience. The Cuban community is smaller and less established, but perhaps has even more potential on a per-person basis, given lower costs of living and very similar needs. They are two nations with dysfunctional economies, a history of high inflation and capital controls, where money is hard to get in or out, and large diasporas of family members who have emigrated to more stable and/or wealthier neighbouring states. Hive helps in all these regards, providing the potential for growing a robust economic network, given enough time. As Hispanic nations in or adjacent to the Caribbean, there is also a synergy in creating Spanish-language content that may help create interest in Hive across nearly the entirety of the latin American world.

The first image in this post is public domain. The others are my own.