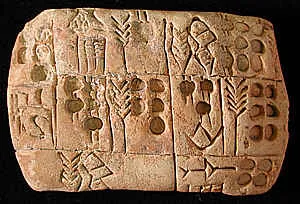

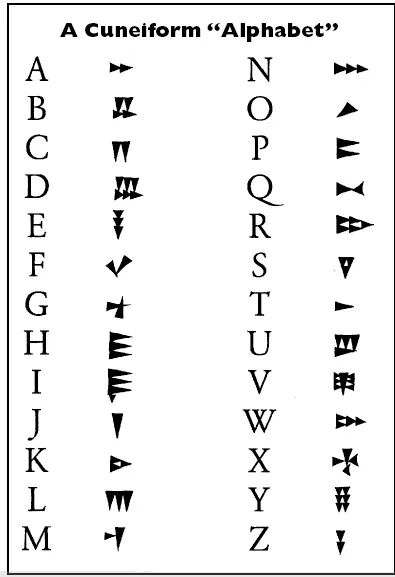

Clay was molded into the records of the ancient world, as well as its bricks, tiles and pots. From before 3000 BC, the Sumerians of ancient Mesopotamia kept records by drawing pictures on soft clay tablets with a pointed stylus, then leaving the tablets to harden in the sun. During the next 200-300 years, the pictures evolved into symbols composed of triangular or wedge-shaped imprints in the clay, made using the straight-cut end of a reed stylus. This script is known as cuneiform, from cuneus, Latin for 'wedge'.

Building words out of syllables

Cuneiform symbols could represent abstract ideas, as well as objects. This sometimes caused confusion. For example, a circle of heat and time associated with it. Instead of creating even more symbols, scribes began to join two or more symbols together to form more complex words. It is as if, in English, to make the word 'treason', we joined the words 'tree' and 'sun'. In this way, short words came to represent the syllables of a longer word with a different meaning, and came to have a phonetic value. Initially the system included around 1200 symbols.

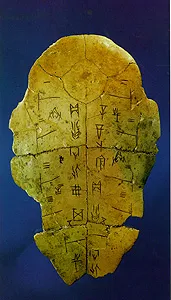

The Chinese developed a different system of writing. The earliest examples, dating back to about 1700 BC, are simple pictures of everyday objects and activities. Each character represented a whole word, rather than just a sound; more than 9000 characters were in use by AD 220.

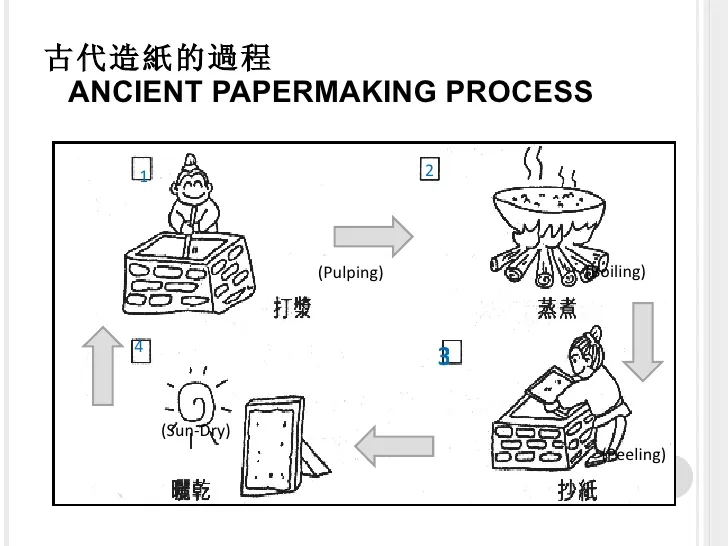

Making paper out of pulp

The art of paper making had been known in the Far East since AD 105 when a Chinese court official Tsai Lun, soaked a mixture of rags, hemp and bark in water, then drained the pulp over a flat sieve. The fibers formed a sheet of wet paper which dried to form a writing surface. By the early 2nd century the Chinese were making paper from bamboo. They soaked the shoots, then boiled, pounded and washed them to form a pulp. They squeezed out the water in a press, and hung the sheets on walls to dry. From the 6th century the Japanese were practicing a similar method using bark. In western Europe, meanwhile, scribes relied on parchment and vellum- the specially treated skins of sheep and goat. It was not until AD 751 that some Chinese soldiers revealed the secret of paper making to their Arab captors, who set them to work making paper in Samarkand, whence it spread throughout the Arab world and into Europe.

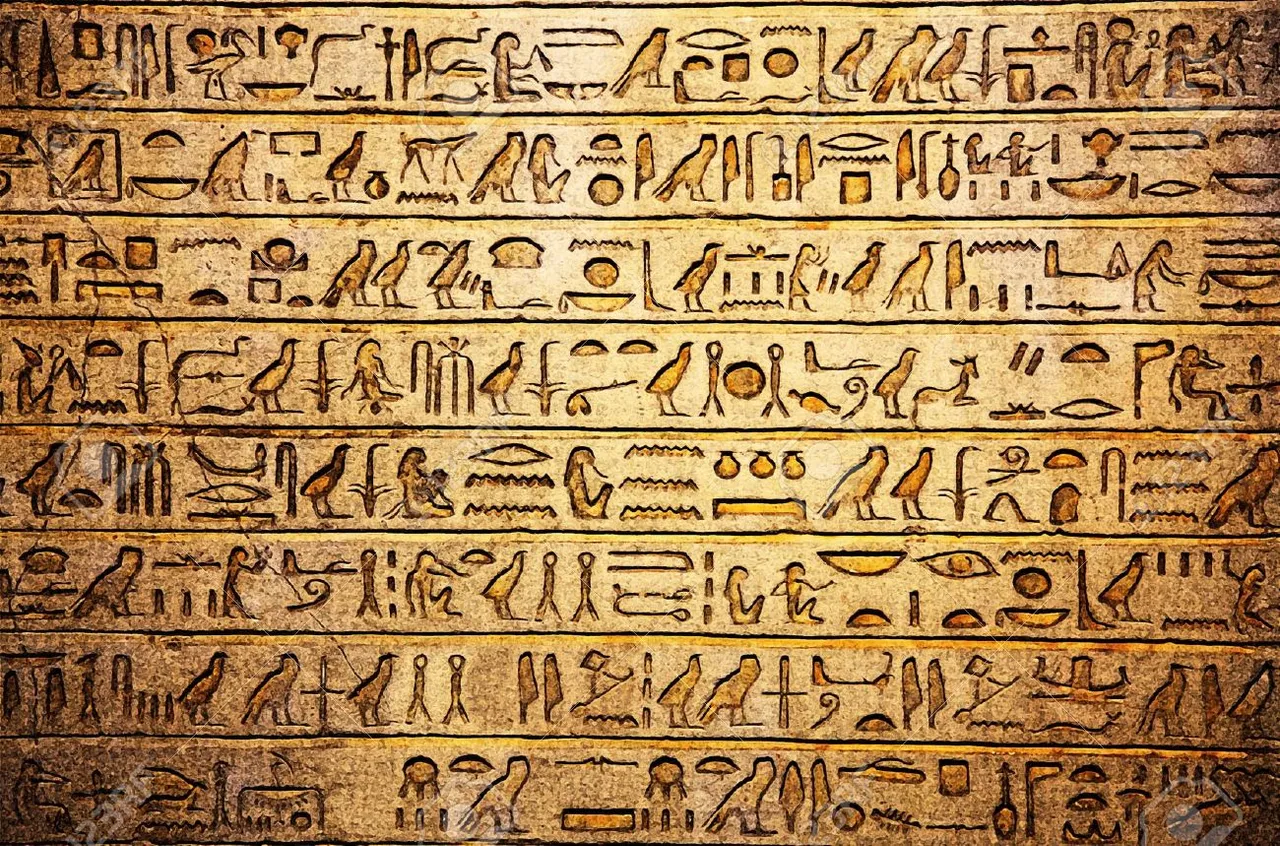

Egypt's sacred carvings

At about the same time as the Sumerians began to write on clay tablets, in the third millennium BC, the Egyptians were developing their own distinctive writing method. Their system, which we call hieroglyphs (from the Greek for 'sacred carvings'), comprised pictures representing everyday objects: a feather, a beetle, a bird. Some signs stood for what they portrayed, but other signs had phonetic value, representing one or two sounds rather than a whole word. Only the consonants were written.

Hieroglyphs retained their pictorial character, and so often had a decorative function. When carved directly onto stone monuments, inscriptions had to be drafted carefully in ink on the stone before being finally carved and painted. Other more everyday writing surfaces were available for scribes, including special writing boards and old shards of pottery.

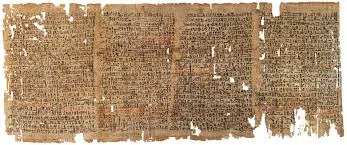

The Egyptians also kept records on papyrus, a paper-like material made from tall reedy plants which thrived on the banks of the Nile. Laborers cut the fibrous stems of the plant into thin strips, laying them side by side. They added a second layer on top, at right angles to the first, and pounded them together until starchy sap from the fibers bound them. After the sheets had dried in the sun, they were ready to be written on using brushes or pens made from thin reeds, cut at the end to form a nib. Scribes used black ink made from pulverized charcoal or soot, and colored inks, especially red, based on ground minerals mixed with water. Papyrus was very expensive, so texts were often erased and the sheets used a second time. Limestone and pottery were cheaper and used for less important documents. Costly parchment was only used for the most valuable documents.