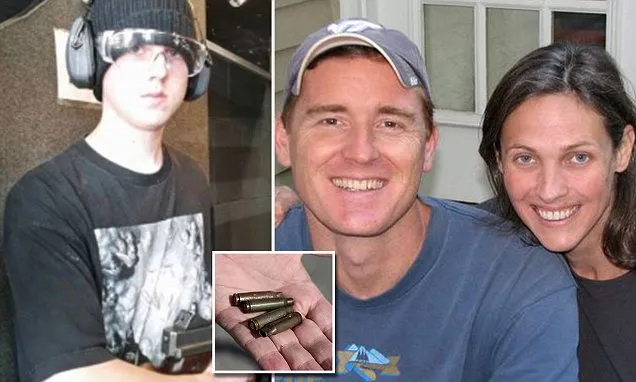

If this kid were an Arab Muslim, he'd be called a terrorist and a part of an international death cult. It would be said, perhaps, that social media had radicalized him.

But it happens that he's white and non-Muslim, so he's "troubled" and has "mental health issues."

I submit that the facts otherwise need no material changes at all for the analogy to be nearly perfect. The cases of recruitment into ISIS or the violent alt-right are for all I can tell nearly identical. Right down to the international death cult.

But what I mean here is actually complicated. I don't think it's sufficient or even necessarily appropriate to talk about violent jihadists merely as "troubled" or as suffering from mental health issues. And I don't think that it's right to soften the actions of violent alt-right individuals in this way either. Yet the social media, peer, and ideological pressures in each case deserve more common conceptualization than they seem to be getting. Just as violent jihadism is the ugliest side of present-day Islam, the alt-right is the ugliest side of present-day western civilization.

I happen to love western civilization, and I will defend its virtues both openly and proudly--but I abhor the alt-right. And I know that there are many who love Islam, and who for that very reason abhor violent jihadism. A common vocabulary for Islam's and the West's analogous failure modes seems potentially much more clarifying than not.

Is mental health a factor? Emphatically yes. You are probably less likely get involved in either of these failure modes if you're not going through some pretty difficult places already. These death cults recruit the vulnerable. That's always been a standard practice of high-investment ideological and religious groups anyway--including the high-investment benign ones. Even Jesus recruited among the troubled and the outcasts, because he knew what he was doing. Yet troubled people are also at risk from harmful spiritual or ideological leaders. And this means that mental health is never going to tell the whole story, even as it's a part of the story.

The other parts are more common than we may be comfortable admitting, I believe.