Chapter 2-12 of the Book of Joshua recount the story of the Conquest of Canaan. The Israelite forces are led by Moses’ successor Joshua Ben Nun. But did such a man ever exist?

In the preceding article in this series, we examined the concept of a Deuteronomistic History. According to this hypothesis, the story of the conquest is largely a piece of fiction, albeit one that draws upon genuine traditions. Was the figure of Joshua borrowed from those traditions? Or was Joshua created out of thin air to serve a theological purpose?

The traditions concerning Joshua that Louis Ginzberg has collected in The Legends of the Jews do not fill us confidence that such a man ever existed. Here is how he is introduced:

The early history of the first Jewish conqueror in some respects is like the early history of the first Jewish legislator. Moses was rescued from a watery grave, and raised at the court of Egypt. Joshua, in infancy, was swallowed by a whale, and, wonderful to relate, did not perish. At a distant point of the sea-coast the monster spewed him forth unharmed. He was found by compassionate passers-by, and grew up ignorant of his descent. The government appointed him to the office of hangman. As luck would have it, he had to execute his own father. By the law of the land the wife of the dead man fell to the share of his executioner, and Joshua was on the point of adding to parricide another crime equally heinous. He was saved by a miraculous sign. When he approached his mother, milk flowed from her breasts. His suspicions were aroused, and through the inquiries he set afoot regarding his origin, the truth was made manifest. (Ginzberg 3)

But these legendary tales are probably of later date than the historical events associated with Joshua. The Biblical account of Joshua and his deeds is not nearly as hard to swallow.

Joshua in the Bible

Joshua is mentioned several times in the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament, which precede the Book of Joshua:

- Joshua is chosen by Moses to lead the Israelites on the battlefield against the Amalekites at Rephidim, the last Station of the Exodus before the Mountain of God:

And Moses said unto Joshua, Choose us out men, and go out, fight with Amalek: to morrow I will stand on the top of the hill with the rod of God in mine hand. So Joshua did as Moses had said to him, and fought with Amalek: and Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of the hill. And it came to pass, when Moses held up his hand, that Israel prevailed: and when he let down his hand, Amalek prevailed. But Moses hands were heavy; and they took a stone, and put it under him, and he sat thereon; and Aaron and Hur stayed up his hands, the one on the one side, and the other on the other side; and his hands were steady until the going down of the sun. And Joshua discomfited Amalek and his people with the edge of the sword. (Exodus 17:9-13)

- At the Mountain of God, Joshua is Moses’ minister שרת:

And Moses rose up, and his minister Joshua: and Moses went up into the mount of God. (Exodus 24:13)

- When Moses comes down from the Mountain of God, it is Joshua who first encounters him and tells him of a commotion in the camp. It transpires that the Israelites are dancing around the Golden Calf:

And when Joshua heard the noise of the people as they shouted, he said unto Moses, There is a noise of war in the camp. (Exodus 32:17)

- In the following chapter, Joshua is described as a young servant who attends Moses in the Tabernacle (Tent of Meeting):

And the Lord spake unto Moses face to face, as a man speaketh unto his friend. And he turned again into the camp: but his servant Joshua, the son of Nun, a young man, departed not out of the tabernacle. (Exodus 33:11)

- In the Book of Numbers, Joshua is again depicted as a young servant of Moses:

And Joshua the son of Nun, the servant of Moses, one of his young men, answered and said, My lord Moses, forbid them. (Numbers 11:28)

- Joshua is one of the Twelve Spies sent out by Moses to reconnoitre the Land of Canaan. In this passage, we are told that he was originally called Oshea or Hoshea (הושע) but Moses renamed him Joshua or Jehoshua (יהושע):

Of the tribe of Ephraim, Oshea the son of Nun ... These are the names of the men which Moses sent to spy out the land. And Moses called Oshea the son of Nun Jehoshua. (Numbers 13:8 ... 16)

- Of the Twelve Spies, Joshua and Caleb are the only ones who advise Moses to proceed with the conquest. For this they are the only ones who will live to enter the Promised Land:

And Joshua the son of Nun, and Caleb the son of Jephunneh, which were of them that searched the land, rent their clothes: And they spake unto all the company of the children of Israel, saying, The land, which we passed through to search it, is an exceeding good land. If the Lord delight in us, then he will bring us into this land, and give it us; a land which floweth with milk and honey. Only rebel not ye against the Lord, neither fear ye the people of the land; for they are bread for us: their defence is departed from them, and the Lord is with us: fear them not ... Doubtless ye shall not come into the land, concerning which I sware to make you dwell therein, save Caleb the son of Jephunneh, and Joshua the son of Nun ... But Joshua the son of Nun, and Caleb the son of Jephunneh, which were of the men that went to search the land, lived still ... For the Lord had said of them, They shall surely die in the wilderness. And there was not left a man of them, save Caleb the son of Jephunneh, and Joshua the son of Nun. (Numbers 14:6-9 ... 30 ... 38 ... Numbers 26:65)

- In Numbers 27, Joshua is chosen by God to be Moses’ successor:

And Moses spake unto the Lord, saying, Let the Lord, the God of the spirits of all flesh, set a man over the congregation, Which may go out before them, and which may go in before them, and which may lead them out, and which may bring them in; that the congregation of the Lord be not as sheep which have no shepherd. And the Lord said unto Moses, Take thee Joshua the son of Nun, a man in whom is the spirit, and lay thine hand upon him; And set him before Eleazar the priest, and before all the congregation; and give him a charge in their sight. And thou shalt put some of thine honour upon him, that all the congregation of the children of Israel may be obedient. And he shall stand before Eleazar the priest, who shall ask counsel for him after the judgment of Urim before the Lord: at his word shall they go out, and at his word they shall come in, both he, and all the children of Israel with him, even all the congregation. And Moses did as the Lord commanded him: and he took Joshua, and set him before Eleazar the priest, and before all the congregation: And he laid his hands upon him, and gave him a charge, as the Lord commanded by the hand of Moses. (Numbers 27:15-23)

- In Numbers 32, Caleb and Joshua are named as the only two men of those that came out of Egypt with Moses who survived to enter the Promised Land:

Surely none of the men that came up out of Egypt, from twenty years old and upward, shall see the land which I sware unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob; because they have not wholly followed me: Save Caleb the son of Jephunneh the Kenezite, and Joshua the son of Nun: for they have wholly followed the Lord. (Numbers 32:11-12)

- Joshua and Eleazar the priest are appointed to distribute the conquered lands of Canaan and Transjordan among the Tribes of Israel:

These are the names of the men which shall divide the land unto you: Eleazar the priest, and Joshua the son of Nun. (Numbers 34:17)

- In the opening chapter of the Book of Deuteronomy, God prophesies to Moses that Joshua will conquer Canaan:

But Joshua the son of Nun, which standeth before thee, he shall go in thither: encourage him: for he shall cause Israel to inherit it. (Deuteronomy 1:38)

- Moses tells Joshua that he shall be as successful in the Conquest of Canaan as Moses has been in the Conquest of Transjordan:

And I commanded Joshua at that time, saying, Thine eyes have seen all that the Lord your God hath done unto these two kings: so shall the Lord do unto all the kingdoms whither thou passest ... ... and the Lord said unto me ... But charge Joshua, and encourage him, and strengthen him: for he shall go over before this people, and he shall cause them to inherit the land which thou shalt see. (Deuteronomy 3:21 ... 26 ... 28)

- Moses inaugurates Joshua as his successor:

And Moses went and spake these words unto all Israel ... The Lord thy God, he will go over before thee, and he will destroy these nations from before thee, and thou shalt possess them: and Joshua, he shall go over before thee, as the Lord hath said ... And Moses called unto Joshua, and said unto him in the sight of all Israel, Be strong and of a good courage: for thou must go with this people unto the land which the Lord hath sworn unto their fathers to give them; and thou shalt cause them to inherit it. And the Lord, he it is that doth go before thee; he will be with thee, he will not fail thee, neither forsake thee: fear not, neither be dismayed ... And the Lord said unto Moses, Behold, thy days approach that thou must die: call Joshua, and present yourselves in the tabernacle of the congregation, that I may give him a charge. And Moses and Joshua went, and presented themselves in the tabernacle of the congregation ... And he gave Joshua the son of Nun a charge, and said, Be strong and of a good courage: for thou shalt bring the children of Israel into the land which I sware unto them: and I will be with thee. (Deuteronomy 31:1 ... 3 ... 7-8 ... 14 ... 23)

- Joshua and Moses recite the so-called Song of Moses to the Israelites:

And Moses came and spake all the words of this song in the ears of the people, he, and Hoshea the son of Nun. (Deuteronomy 32:44)

Joshua, then, is depicted as a young servant, attendant or minister of Moses, who eventually becomes his successor. This is nothing inherently implausible in any of this. There are, however, some discrepancies in the preceding passages. For example, Joshua is chosen by Moses to lead the Israelites in battle against the Amalekites. This seems a rather onerous and daunting task for someone who is afterwards described as a young servant and whose duties are to attend Moses in the Tabernacle. He also seems to serve as the custodian of the Tabernacle, a position that one would hardly give to a military commander.

According to the Seder Olam Rabbah, a rabbinical chronology of Biblical events, Joshua was 110 years old when he died (Guggenheimer 120). If, however, we subtract forty years from this total—in this series of articles, I have theorized that the Exodus only lasted one or two years, not forty—he dies in his early seventies, which is easier to swallow. The Seder Olam Rabbah allots seven years to the Conquest and a further seven years to the distribution of the conquered lands (Guggenheimer 116-117).

Historicity of Joshua

A few centuries ago, no Biblical scholar would have questioned the historicity of Joshua. Today, however, the prevailing scholarly view is that Joshua is a literary creation of a later age—or at best a legendary figure of little historical value. Between the two extremes of total acceptance and total rejection lies the belief that while the Book of Joshua falls short of being a true and accurate account of the Conquest of Canaan, it is nonetheless based on genuine historical traditions:

That the narratives concerning the life and work of [Joshua] rest in the main upon a basis of tradition can hardly be doubted. How far the details have been modified, or a different coloring imparted in the course of a long transmission, it is impossible to determine. There is a remarkable similarity or parallelism between many of the leading events of [Joshua’s] life as ruler and captain of Israel and the experiences of his predecessor Moses, which, apart from any literary criticism, suggests that the narratives have been drawn from the same general source, and subjected to the same conditions of environment and transmission. (Orr 1747)

In the middle of the 20th century, William Foxwell Albright and his student George Ernest Wright promoted the doctrine now known as historical maximalism, according to which archaeological discoveries were believed to have confirmed in a large measure the historicity of the events depicted in the Old Testament, including the Book of Joshua. Since Albright’s death in 1971, however, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction, towards historical minimalism, which is characterized by a much more skeptical approach to the Biblical texts.

This prevailing attitude is far from unanimous, and there remain many scholars of repute who reject the view that the Joshua depicted in the Old Testament is a fictional figure of a later age. These are not Fundamentalists, who blindly accept every word of the Book of Joshua. They are critical scholars, who believe that the Biblical text, when placed in its proper literary context, can be reconciled with the latest discoveries of the archaeologists:

The recent discussions on the origins of Israel have grown out of the demise of the conquest model and the rise of more archaeological, sociological, and anthropological approaches toward reconstructing Israel’s early history. While there seems to be something of a school developing that believes the Israelites were indigenous to Canaan, there is little evidence to support this assertion. Despite the current movement towards minimalist and reductionist readings of the biblical text and the elevation of the newer approaches, Siegfried Herrmann has argued for more traditional, text-based methods to answer the problems of Israel’s origins. He maintains, “we need theories with a closer connection to the biblical and extrabiblical texts, together with careful consideration of the archaeological results. The question is which source provides some certainty regarding the real Israelite Settlement in the premonarchial period? This is a very old question, but should be raised afresh in order to limit new theories and speculations” [Herrmann 47]. I agree with Herrmann’s assessment ...

When Joshua is viewed as a piece of Near Eastern military writing, and its literary character is properly understood, the idea of a group of tribes coming to Canaan, using some military force, partially taking a number of cities and areas over a period of some years, destroying (burning) just three cities, and coexisting alongside the Canaanites and other ethnic groups for a period of time before the beginnings of monarchy, does not require blind faith. Finally, the idea that the Israelites would have destroyed and leveled cities indiscriminately, makes little sense for they intended to live in this land. A scorched-earth policy is only logical for a conqueror who has no thought of occupying the devastated land. After the battles had been fought and the land divided up among the tribes, Israel is said to have occupied “a land on which you have not labored, and cities which you had not built, and you dwell therein; you eat the fruit of vineyards and oliveyards which you did not plant” (Josh. 24:13). This suggests that the arrival of the Israelites did not significantly affect the cultural continuity of the Late Bronze Age and may explain why there is no evidence of an intrusion into the land from outsiders, for they became heirs of the material culture of the Canaanites. (Hoffmeier 43-44)

This approach opens the way for scholars to accept in broad outline the story of the Conquest and Settlement of Canaan by the Israelites as depicted in the Book of Joshua, while at the same time casting doubt on the historicity of the figure of Joshua himself. If the Conquest was a lengthy process, pursued on different fronts by different Tribes of Israel, there is no longer any need for a single heroic leader. The question of Joshua’s historicity becomes of secondary importance. What matters is the Conquest: Did it or did it not happen? This seems to be the attitude of Kenneth Kitchen and James K Hoffmeier, both of whom argue for a military or quasi-military invasion, conquest and colonization of Canaan by the Israelites, while leaving the question of Joshua’s historicity to one side:

[At] the end of the day, we should speak of an Israelite entry into Canaan, and settlement: neither only a conquest (although raids and attacks were made), nor simply an infiltration (although some tribes moved in alongside Canaanites), nor just re-formation of local Canaanites into a new society “Israel” (although others, as at Shechem, may have joined the Hebrew nucleus; cf. Gibeon). But elements of several processes can be seen in the biblical narratives. (Kitchen 190)

Another theory, which runs along similar lines, argues that Joshua was a historical figure who successfully invaded and conquered the territory traditionally allotted to the Tribe of Ephraim. Joshua was a member of this tribe, and the town of Timnath-heres, which was given to him as his inheritance, lay in the hill-country of Ephraim. In The Jewish Encyclopaedia, Emil G Hirsch, Professor of Rabbinical Literature and Philosophy at the University of Chicago, has defended this position:

Joshua’s historical reality has been doubted by advanced critics, who regard him either as a mythological solar figure ... or as the personification of tribal reminiscences crystallized around a semi-mythical hero of Timnath-serah (= Timnat Heres). Eduard Meyer, denying the historicity of the material In the Book of Joshua, naturally disputes also the actuality of its eponymous hero ... These extreme theories must be dismissed. But, on the other hand, it is certain that Joshua could not have performed all the deeds recorded of him. Comparison with the Book of Judges shows that the conquest of the land was not a concerted movement of the nation under one leader; and the data concerning the occupation of the various districts by the tribes present so many variants that the allotment in orderly and purposed sequence, which is ascribed to Joshua, has to be abandoned as unhistorical.

Yet this does not conflict with the view that Joshua was the leader of a section of the later nation, and that he as such had a prominent part in the conquest of the districts lying around Mount Ephraim. The conquest of the land as a whole was not attempted; this final achievement was the result of several successive movements of invasion that with varied success, and often with serious reverses, aimed at securing a foothold for the Israelites in the trans-Jordanic territories. Joshua was at the head of the Josephite (Leah) tribes (comp. Judges i. 22, according to Budde; Joshua dies at the age of 110, as does Joseph), for whom the possession of the hill-country of Ephraim—Gibeon in the south and Ebal in the north—was the objective point. This invasion on the part of the Josephites was probably preceded by others that had met with but little success (comp. the story of the spies. Num. xiv.). But the very fact that while earlier expeditions had failed this one succeeded impressed for centuries the imagination of the people to such an extent that the leader of this invasion (Joshua) became the hero of folk-lore ; and in course of time the plan of the conquest of the whole land and its execution were ascribed to him. He thus grew to be in tradition the leader of the united people—especially in view of the supremacy enjoyed by the tribe of Joseph, in whose possession was the Ark at Shiloh—and therefore the successor of Moses, and as such the chief in authority when the land was divided among the tribes.

Recollections of valorous feats performed in the days of these fierce wars with the aboriginal kings were transferred to Joshua and his time; battles remembered in fable and in song were connected with his name; natural phenomena (the blocking of the waters of Jordan by rocks, the earthquake at Jericho, the hail-storm before Gibeon) which had inspired semi-mythological versions were utilized to enhance his fame ... This process is perfectly natural, and has its analogues in the stories concerning other heroes ... But all this makes the historical reality of Joshua as the chief of a successful army of invasion all the more strongly assured. The chapters dealing with the division of the land must be dismissed as theoretical speculation, dating from a period when the tribal organization had ceased to exist; that is, from the Exile and perhaps later. The epilogues (the story of Joshua’s gathering the elders or the whole people at Shechem before his death, Josh, xxiii.-xxiv. 28) are clearly the work of a Deuteronomic writer ... The cruelty imputed to Joshua—the ban against Jericho, for instance—is a trait corroborative of the historical kernel of the military incidents of his biography. (Singer 283)

Conclusions

The historicity of Joshua is a matter of secondary importance to our studies. What we would really like to know is whether there was a Conquest of Canaan. And if there was, what was its nature? In the next two articles in this series, we will look at the opinions of Kenneth Kitchen and James Hoffmeier and assess them in the light of the Short Chronology.

And that’s a good place to stop.

To be continued ...

References

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 4, Translated from the German by Paul Radin, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1913)

- Heinrich W Guggenheimer, Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology, Rowman & Littlefield publishers, Inc, Lanham, MD (2005)

- Siegfried Herrmann, Basic Factors of Israelite Settlement in Canaan, in Janet Amitai (editor), Biblical Archaeology Today: Proceedings of the International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem, April 1984, Israel Exploration Society, Jerusalem (1985)

- James K Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1997)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 3, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 7, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1904)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

Image Credits

- Joshua’s Victory over the Amalekites: Nicolas Poussin (artist), Hermitage Museum, ГЭ-1195, Public Domain

- The Adoration of the Golden Calf (Poussin): Nicolas Poussin (artist), National Gallery, London, NG5597, Public Domain

- The Return of the Twelve Spies: Adolf Hult, Bible Primer, The Augustana Synod, Rock Island, IL (1919)

- Moses Blesses Joshua Before the High Priest Eleazar: James Tissot (artist), The Jewish Museum, New York, Public Domain

- The Tribes of Israel and their Territories: © Janz, Creative Commons License

- Joshua, Choir Stalls, Blaubeuren Abbey (Jörg Syrlin the Younger): Jörg Syrlin the Younger (sculptor), © GFreihalter, Creative Commons License

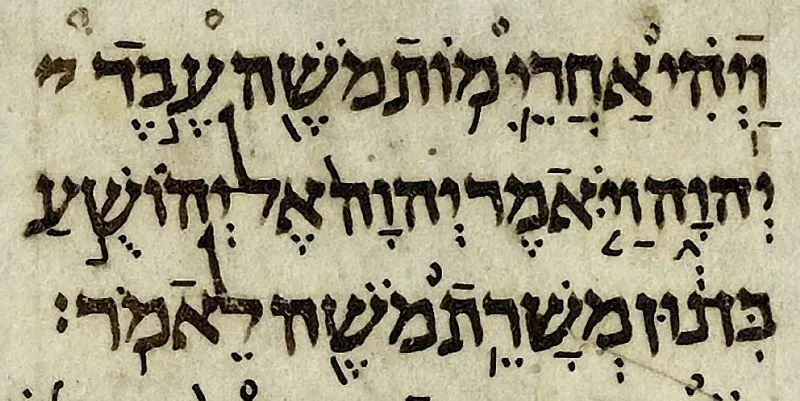

- Joshua 1:1 (Aleppo Codex): Aleppo Codex, 10th Century, Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Public Domain

- James Hoffmeier: © 2020 Trinity International University, Fair Use

- Kenneth A Kitchen: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- E G Hirsch: Faith in the City, Public Domain