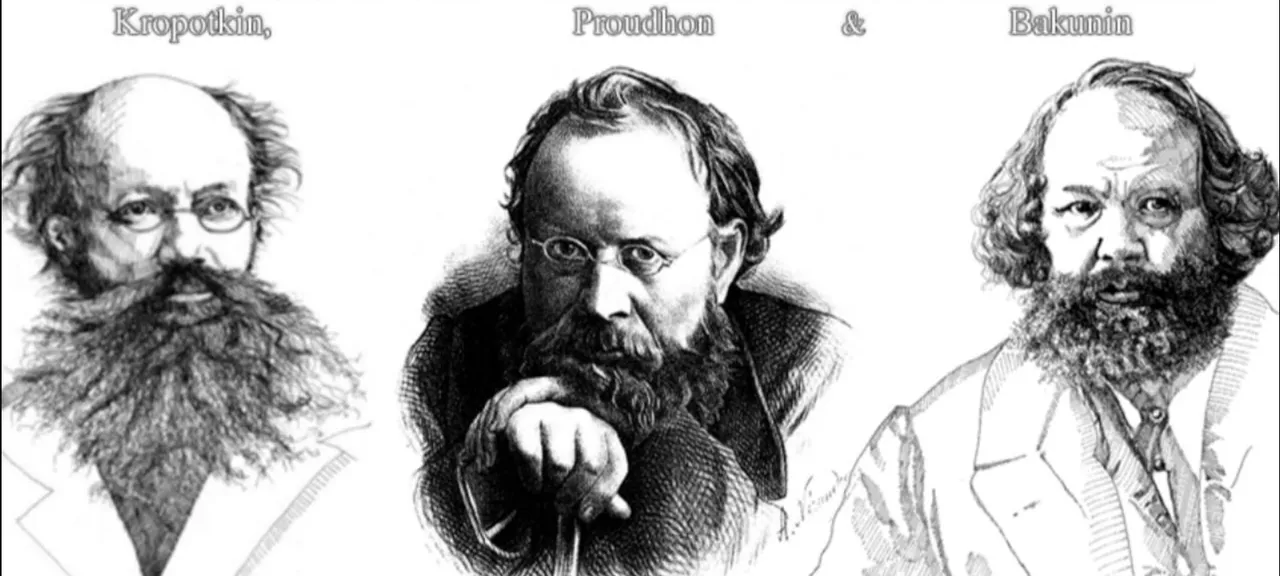

I refer to my political philosophy as libertarian social democracy because I originally envisioned it as a sort of synthesis of libertarian socialism and social democracy. Those two movements, historically, were closely related. Social democracy, as espoused by Eduard Bernstein, Annie Besant, and George Bernard Shaw, was a form of democratic socialism. Libertarian socialism (aka anarchism), as espoused by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, and Peter Kropotkin was also a form of democratic socialism. (Cf. Bookchin Was An Anarchist) The early anarchists advocated a mixture of direct democracy and delegative democracy. Libertarian socialism would be more participatory and decisions would be made from the bottom up, as each "commune" (or municipality) would be autonomous and all social organization would be done on the principle of free association. The various communes would make pacts for mutual aid and defense and organize into vast confederations of autonomous municipalities. Libertarian socialism would be decentralized and confederalist. The democratic socialism of the social democrats, however, followed a more conventional republican approach, seeking to achieve its goals through representative democracy, without necessarily emphasizing decentralization or municipal autonomy, at least not as being absolute goods. The section on the organization of society in Fabian Essays in Socialism, an early treatise on social democratic philosophy, very much resembled the proposals of the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. I thought that something like liquid democracy, a sort of compromise between direct democracy and representative democracy, could be used to make social democracy more libertarian. I also thought that digital direct democracy and ranked-choice voting might be viable mechanisms for making democratic institutions more libertarian.

There were several schools of libertarian socialism that really influenced me. The first was mutualism, the philosophy of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Proudhon held that society ought to be reorganized on a more thoroughly democratic basis, using something more like direct democracy and greatly limiting arbitrary power. He held that all land ought to be communally owned and managed by the local commune or municipality. Rent would be paid to the municipality and the municipality would be in charge of building and maintaining homes. Additionally, Proudhon thought that ownership of industry ought to be handed over to the workers. Other libertarian socialists, like Peter Kropotkin and Joseph Déjacque, pushed for communist anarchism and advocated communal-ownership of land too, but they had held that money and markets ought to be abolished. In their vision of utopia, everyone would continue to work and produce things but all the products would be placed into common stores, where people could freely take what they need. This would be a society based on the communist principle "from each according to their ability, to each according to their need." Then there were the Ricardian socialists, like Thomas Hodgskin, and individualist anarchists, like Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner, who made the case for free trade. The existence of such libertarian socialists, who advocated free trade, is the primary reason that the term "libertarian" has come to be associated with free-market philosophies. My idea of libertarian social democracy does borrow heavily from all three of these schools of libertarian socialist thought: mutualism, communist anarchism, and Ricardian/individualist anarchism.

Over time, I came to drift away from socialism proper. I came to be more sympathetic to geo-libertarianism as an analogue to socialism. (Most social democrats, by the way, no longer advocate outright socialism, but advocate taxation, welfare, and redistribution as analogues to socialism.) Georgism, or geo-libertarianism, is a school of thought based on the ideas of Henry George. Henry George held that land ought to be communally-owned and that people who want to monopolize that land for private use ought to be required to pay rent to the community for such a privilege. However, George did not advocate outright socialism, where government or the community would confiscate land from private individuals. Instead, he thought that a sufficient analogue to communal ownership could be created through taxation. Government could start taxing people on the value of their land. Since a person is entitled to the entire product of their own labor, buildings and improvements would not be taxed; the value of the land alone would be subject to taxation. This land value tax would function as an analogue to rent. It would be just as if all land was communally-owned and the community were charging rent for private use of it. Thus, land value tax could be looked at either as a scheme for communal-ownership of land or as a scheme to simplify taxes and lead to less interference by government. Henry George was also an advocate of free trade and advocated land value tax because it would minimize government interference in the marketplace.

Geo-libertarianism overlaps with the libertarian socialism (mutualism) of Proudhon, as well as with the democratic socialism of classical social democrats like Annie Besant and George Bernard Shaw. In fact, Proudhon himself did advocate communal-ownership of land and collection of ground-rent by the municipality. Some of his proposals were remarkably similar to Henry George's. There is even a school of anarchism known as geo-mutualism, which attempts to synthesize Proudhon's anarchism with Henry George's philosophy. (Cf. On Anarchist Social Democracy: Taxation, Welfare, and Anarchy) But geo-libertarianism also overlaps with classical social democratic theory. Where classical social democrats or democratic socialists differed from Henry George was in the contention that all revenue collected from land value taxes ought to go to paying workers in government-owned industries. While the classical social democrats agreed with Henry George in asserting that land and natural resources ought to be publicly owned and rented out, they only saw Georgism "as a transition stage to Social Democracy," holding that communal-ownership of both land and industry was necessary. (Cf. Graham Wallas, Property Under Socialism in Fabian Essays in Socialism) This is what distinguishes Georgism from socialism. Socialism holds that industry too must be owned and operated socially or communally. Most modern social democrats have dropped socialism proper and no longer hold that industry should be publicly owned.

My social democracy is libertarian in the sense that it is rooted in libertarian socialism and geo-libertarianism. While I no longer advocate libertarian socialism, the model that I currently propose is rooted in a dialogue internal to libertarian socialism. On the one hand, I agree with Proudhon's critique of private property and, on the other, I agree with Joseph Déjacque's critique of Proudhon. If you really want to understand how my current position is rooted in libertarian socialist theory, you can check out my article Libertarian Social Democracy: Delegative Democracy, Land Value Tax, & Universal Basic Income. While I have ultimately rejected the conclusions drawn from libertarian socialist analysis by the libertarian socialists themselves, I have embraced alternative solutions that I believe are analogous to, and functionally isomorphic to, the solutions that they recommended. I advocate a Georgist land value tax as an analogue to communal-ownership of land and universal basic income, funded by that land value tax, as an analogue to communism. Thus, my model does meet the classical criteria of "to each according to their need," insofar as basic income would guarantee access to necessities. Libertarian social democracy essentially swaps the socialism of the libertarian socialists for Georgism, then adds the universal healthcare and welfare proposals of the social democrats on top of it. Additionally, I emphasize maximizing individual liberty: marijuana, prostitution, "sodomy," and public nudity would all be totally legal. Consequently, my variation on social democracy is libertarian in the classical sense, as that term was used by the libertarian socialists who coined the term—it seeks to maximize individual liberty through communal-ownership of land as a mechanism of providing "to each according to their need," while also minimizing the number of rules within society so that people are free to do as they like to the extent that their liberty does not reduce the liberty of others.

It can also be said that my vision of social democracy is libertarian in the sense that it has a geo-libertarian basis. I follow geo-libertarianism in holding that income tax is extremely problematic and holding that all taxes ought to be replaced by land value taxes or similar taxes (e.g. Pigouvian taxes, cap and trade, etc.) that can be justified along Georgist lines. Furthermore, it is libertarian in a limited free-market sense. The framework for markets is a system of private property, a monetary system, contract law, courts or tribunals for adjudication and dispute resolution, and police for the enforcement of rules and court decisions. Following F. A. Hayek, I believe that the role of government is to create the rules to establish social order and that the spontaneous order of the market will emerge from that. The government generally shouldn't arbitrarily intervene. Government ought to create rules that form a framework that allows the market to function without any arbitrary intervention. Any intervention that does take place ought to be standard and uniform, following the principle of isonomy or "equal law," simply laying out the rules of the game rather than acting on a whim. The government intervenes to protect property rights, and the rules governing property are uniform. The government can likewise intervene to collect land value tax, and that intervention will follow standard rules rather than arbitrary whims. Additionally, rules and regulations may be imposed on corporations so that they are prohibited from polluting or are fined for polluting, and those rules shall be uniform and standard, not subject to the arbitrary whim of functionaries. In this regard, I have been influenced by libertarians like F. A. Hayek and Hernando de Soto Polar, but also by ordoliberalism and the realization that markets aren't perfect. I believe that markets do sometimes fail. Consequently, government ought to intervene in the market in order to correct market failures. I recognize "the need for the state to ensure that the free market produces results close to its theoretical potential."(Wikipedia) (Cf. Markets Are Not Perfect)

Additionally, I have been influenced by the notion of dialectical libertarianism, which holds that a formally statist intervention may be libertarian if the overall effect happens to bring about results that more closely approximate the theoretical ideal of laissez-faire than the same system would without that intervention. For instance, if a government has already granted an artificial monopoly to a private company, setting a limit on prices that that company can charge would actually be more functionally libertarian than if the government were to do nothing. Under pure competition, that company would not be able to charge as much. (Cf. Chris Sciabarra, Total Freedom: Toward A Dialectical Libertarianism)

Furthermore, my model of libertarian social democracy is aimed at maximizing liberty in the civic republican sense. (Cf. Philip Pettit, Quentin Skinner, et al.) That, however, is a topic for a future post, so I won't elaborate on it here.

To summarize, my model of libertarian social democracy is libertarian insofar as it draws on a broad libertarian tradition, which includes libertarian socialism, geo-libertarianism, Hayekian libertarianism, and dialectical libertarianism.