According to the philosopher, Stephen Hicks, modernism’s foundations are located in its profound confidence in reason and science. It is an era that revolts against the pre-modern reliance upon tradition, faith, and mysticism. Thinkers like Francis Bacon (1561-1626), René Descartes (1596-1650) and John Locke (1632-1704) are constitutive to modernism. Although it is difficult to point out exactly when modernism began and where it ended, we can roughly say that it’s a 17th to late 19th century era.

What do modern philosophers have in common?

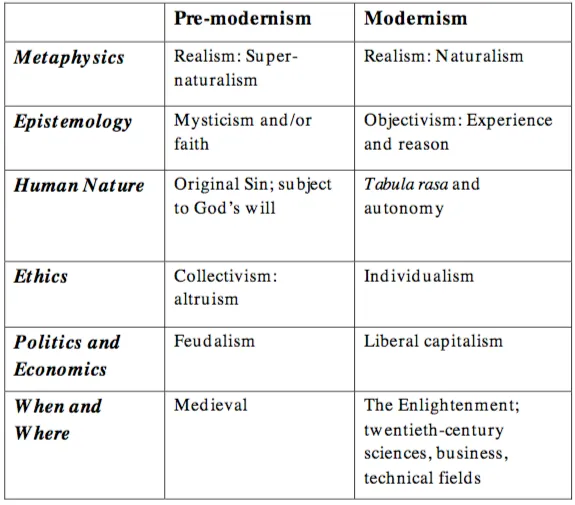

Modern philosophers start from nature, instead of the supernatural which was common for Medieval philosophers. They departed from pre-modernist philosophers on many important areas.

Figure 1: contrasting pre-modernism with modernism.

Modern thinkers stress the importance of reason, science, and individual autonomy. They believe that the world can be explored through reason instead of faith in the supernatural, and that the individual is the unit of value instead of political, social or religious authorities.

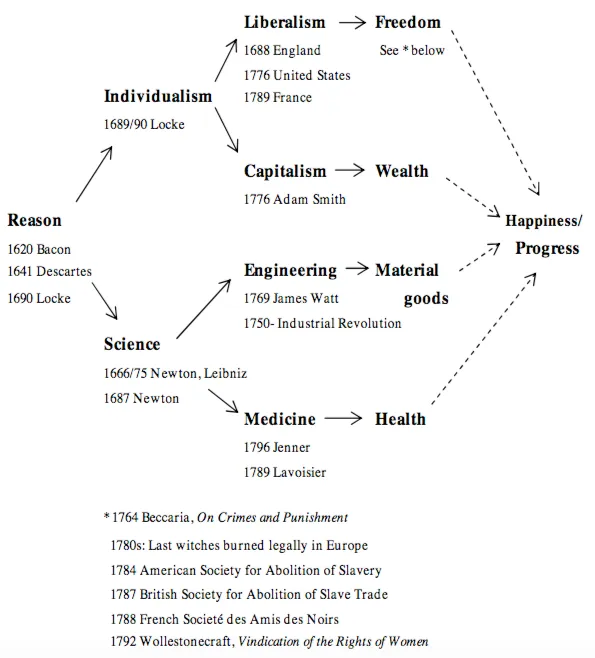

Although modern thinkers disagreed among themselves and often held competing or conflicting ideas, Descartes’ account of reason is for example rationalist while Bacon’s and Locke’s are empiricist, they had never abandoned the central status of reason as objective and competent. This central status of reason eventually culminated in the Enlightenment.

Science

The Enlightenment thinkers laid the foundations of all the major branches in science. Isaac Newton (1666) and Gottfried Leibniz (1675) independently developed calculus.

Medicine

Science applied to the understanding of the human physiology led to medicine. The smallpox vaccine was developed in 1796. The advance of modern medicine led to a decline of infant mortality rates. In London, the death rate of children pre-5 years old fell from 74.5% in 1730-1749 to 31.8% in 1810-1829.

Engineering

Science applied to engineering led to the Industrial Revolution and an increase in the production of material goods. The increased production output per account of labour due to mechanization like the steam engine of James Watt (1769) resulted in more material wealth.

Ethical individualism

John Locke emphasized that reason is a faculty of the individual and maintains that ethical individualism should be at the center of social and political life. He reasoned for individual rights, political equality, a limited power of government, and religious toleration.

Liberalism

Applying ethical individualism to the realm of politics led to liberal democracy. The Western world had thus done away with feudalism. Racism and sexism were on its defense in the 18th century. Societies for the elimination of slavery were formed – in America in 1784, in England in 1787, in France in 1788 - a Declaration of the Rights of Women was written in 1791, and A Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1792. Liberty and equality for all individuals were marching forward.

Liberal capitalism

Applying ethical individualism to economics yields free market capitalism, which is based on the principle that individuals should be left free to make their own decisions about production, consumption, and trade. They are free to own capital. Hence, feudalism and mercantalism declined. Capturing insights of how free markets made everyone more wealthy, Adam Smith wrote in The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759):

Every individual... neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it... he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.

All-in all, modern philosophy made individuals become freer, wealthier, live longer, and enjoy more material comfort.

Figure 2: The Enlightenment vision.

Reference

Hicks, S. (2004). Explaining post-modernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault