This is one of those subjects that I suspect I won't be able to tackle efficiently in a single post, but regardless, I'm going to give it a go. I think I have enough clarity to make sense of it all—but then again, I'm making some assumptions here, and maybe I still have a blind spot to overcome.

For a while now, I've been attempting to come up with a nuanced explanation of the concept of self-worth. A common subject, I know—and one that you're bound to think about, talk about, post about, and learn about throughout your whole life.

The truth is that self-worth is not one thing, per se. Yes, it exists—I'm not denying its existence—but the point I'm attempting to make is that it's more like a collection of sorts. The oversimplifications we tend to use in common conversation are pragmatic, but they offer no insight into edifying it—or protecting it, for that matter.

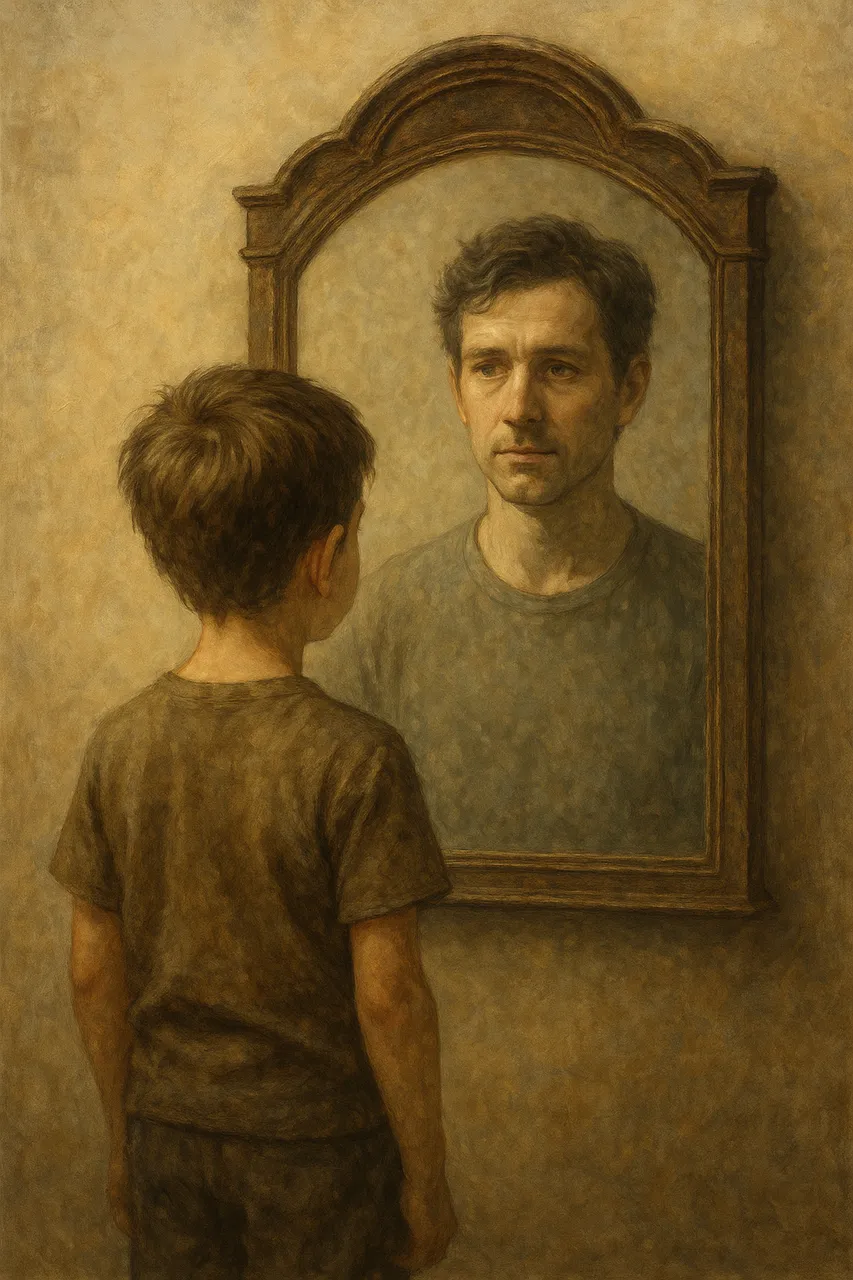

The Seeds Are Planted Early

I suspect the collection that forms our system of self-worth begins at a very early age. We learn—probably before we can put complex sentences together—basic notions about rewards and punishments. A well-behaved child is more likely to get more attention, more affection, and yes, even more treats.

So although the child can't really understand what's happening, he or she is beginning to conceptualize the idea of being worthy. Worthy of love, of praise—or anger, for that matter.

As we age and begin to define our personalities, this initial system of self-worth starts to take a more solidified shape. A pretty girl, for example, might notice that her looks give her an edge over other children. The constant praise she gets—"How beautiful you are"—is a chisel that carves into her subconscious an undisputable reason why she is worthy.

Males—boys, on the other hand—learn that other traits give them worth. A strong boy, one that doesn't cry when hurt or that can lift a heavy item on his own, might be compared to a superhero. He might earn praise from not only the male figures around him but also from women, who find those traits desirable in men. (Yes, this is still the case.)

Not Set in Stone

Although it may seem like I'm about to contradict myself, I'm of the idea that our systems of self-worth are not truly static. Which is to say: adding or removing elements from the intricate web may be difficult, but it's in no way impossible.

It is in this realization—in this self-reflection—that I've found myself attempting to find enough clarity to express my findings to anyone who would care to listen.

I believe that if we wake up to the fact that our self-worth is not static, we can begin to work on improving it. We can remove fragile elements—ephemeral elements—and replace them with more valuable ones. Resilient ones.

The Slippery Slope of Easy Worth

When my niece—now 21—was only 14 years old, I had begun putting a lot of thought into these concepts. I could see her beginning to invest, if you will, in fragile elements—ephemeral ideas of why she was valuable. Not only valuable to us, her family, but more so to her environment, her friends, and of course the boys who began paying attention to her. Blessed with a beautiful face and green eyes, she always found herself ahead of the game. She always drew the attention of boys, and she was beginning to take advantage of it.

To a young mind, it's easy to pick the simpler route. If a girl is getting a lot of attention because of her looks—something she didn't have to work for—then why would she elect to work on something difficult? It hardly seemed worth it.

But that, to me, is why I find this subject fascinating. Because it's obvious that the same old rule applies: nothing easy is truly valuable.

Beauty and Strength Are Expiring Assets

Beauty, for example, is fleeting. There’s not a single woman in the world—no matter how beautiful she might be—that can escape aging. So if her system of self-worth is based solely on her beauty, her expiration date is very well defined.

Likewise, if a man thinks his youth and strength are his only value—when the hair begins to fall off and the muscles begin to ache—he too will find himself fighting against depression.

All this to say: although loving ourselves can be achieved through many routes, there are only a few that are really worth taking.

Being a good son, a good brother, a great friend—these are a lot more valuable long term than any of the traits I mentioned. And yet we hardly talk about these things when we talk about self-worth, or self-esteem, as it's usually called.

The Question That Grounds Me

Obviously, I'm speaking from my perspective as a male, but I submit to you that a similar path is available to all of us.

I try to ask myself one question every time I have doubt about who I am:

Am I investing in things that have real value? My family, my peace, my mind, my soul? Or am I acting like a hedonistic fool?

It's an ugly question—one that can make us feel very uncomfortable. But just like delaying going to the dentist too long and waiting for the pain to be unbearable, waiting for our mistakes to bear fruit is just as dumb—and just as painful.

MenO

Afterword:

I want to give a shoutout to @ladyaryastark for this subject. Her post is what inspired me to sit on my computer for a good hour typing this out.

I've added her as a beneficiary, because honestly, I love when people make me think like she has today. It tingles the brain, as they say.