The Oyster and the Litigants

In this fable, we see that it is often better to not argue stupidly over minor things, as everyone may end up with nothing.

L'Huître et les Plaideurs

Un jour deux pèlerins sur le sable rencontrent

Une huître, que le flot y venait d’apporter :

Ils l’avalent des yeux, du doigt ils se la montrent ;

À l’égard de la dent il fallut contester.

L’un se baissait déjà pour amasser la proie ;

L’autre le pousse, et dit : Il est bon de savoir

Qui de nous en aura la joie.

Celui qui le premier a pu l’apercevoir

En sera le gobeur ; l’autre le verra faire.

Si par là l’on juge l’affaire,

Reprit son compagnon,

j’ai l’œil bon, Dieu merci.

Je ne l’ai pas mauvais aussi,

Dit l’autre ; et je l’ai vue avant vous, sur ma vie.

Hé bien ! vous l’avez vue ; et moi je l’ai sentie.

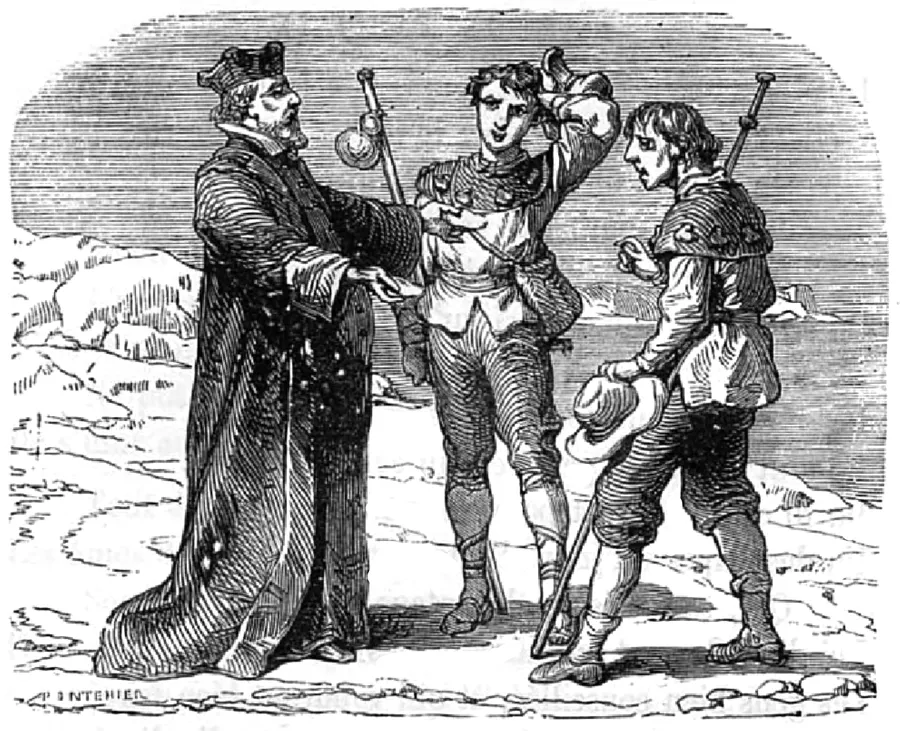

Pendant tout ce bel incident,

Perrin Dandin1 arrive : ils le prennent pour juge.

Perrin, fort gravement, ouvre l’huître, et la gruge,

Nos deux messieurs le regardant.

Ce repas fait, il dit, d’un ton de président :

Tenez, la cour vous donne à chacun une écaille

Sans dépens ; et qu’en paix

chacun chez soi s’en aille.

Mettez ce qu’il en coûte à plaider aujourd’hui ;

Comptez ce qu’il en reste

à beaucoup de familles :

Vous verrez que Perrin tire l’argent à lui,

Et ne laisse aux plaideurs que

le sac et les quilles2.

1: Perrin Dandin est un personnage de fiction issu du roman de Rabelais, le Tiers Livre. Ce nom propre a fini par désigner un juge opportuniste ignare ou avide.

2: Ne leur laisse rien.

The Oyster and the Litigants

One day two blokes on the sand find

An oyster, which the flood had just brought:

They swallow it with their eyes, they point to it;

With regard to the tooth, they started to argue.

One was already stooping to get the prey;

The other nudges him, says: It is good to know

Which of us will have the joy of it.

Whoever saw it first

Will be the guzzler; the other will see eating it.

If by this we judge the case,

Replied his companion,

I have a good eye, thank God.

I don't have one bad myself,

Said the other, and I saw it before you, I swear.

Well! you have seen it; me, I smelled it.

During all this beautiful incident,

Perrin Dandin1 arrives: they take him as a judge.

Perrin, very gravely, opens the oyster, and eats it,

Our two gentlemen looking at him.

This meal done, he says, in a president's tone:

For you, the court gives you each a scale

Without costs; and may everyone

go home in peace.

Think about what it costs to plead today;

Count what is left at the end

for many families:

You will see that Perrin draws the money to him,

And leaves to the litigants only

the bag and the skittles2.

1: Perrin Dandin is a fictional character in a novel of Rabelais, who seats himself judge-wise on the first stump that offers, and passes offhand a sentence in any matter of litigation

2: Old expression that meant that they ended up with nothing.

First Fable: The Circada and the Ant

Previous fable: The Fox and the Stork

Next fable: The Hornets and the Bees

The Life of Aesop, by Jean de La Fontaine - part 4

Xantus had a wife of rather delicate taste, and who did not like all sorts of people: so to go and introduce her seriously to his new slave, was not easy, unless he wanted her to get angry and make fun of him. He thought it better to make a joke of it and went to tell the house that he had just bought the most beautiful and well-built young slave in the world. On this news, the girls who served his wife thought they would beat whoever would have him for his servant; but they were much surprised when the personage appeared. One held her hand to her eyes; the other flees; the other cried out. The mistress of the house said that it was to drive her away that such a monster was brought to her; that the philosopher had long tired of her. Then the disagreement heated up to such an extent that the woman asked for her property and wanted to retire to her parents. Xantus did so much with his patience, and Aesop with his wit, that things settled down. There was no more talk of leaving, and perhaps habituation erased some of the ugliness of the new slave in the end.

I will leave many little things where he displayed the liveliness of his mind; for, although one can judge of his character by this, they are of too little consequence to inform posterity. Here is only a sample of his common sense and his master's ignorance. This one went to a gardener to choose a salad for himself; the herbs picked, the gardener begged him to satisfy his mind on a difficulty which concerned philosophy as well as gardening: that is, that the herbs which he planted and cultivated with great care did not profit, quite the opposite of those that the earth produced of itself without cultivation or amendment. Xantus reported everything to Providence, as one is wont to do when one is short. Aesop laughed; and, having drawn his master aside, he advised him to tell that gardener that he had given him such a general answer because the question was not worthy of him: he, therefore, left him with his boy, who assuredly would satisfy him. Xantus went then for a walk on another side of the garden. Aesop compared the earth to a woman who, having children by a first husband, would marry a second who would also have children by another wife: his new wife would not fail to conceive of aversion for these, and would take food from them so that his people might enjoy it. So it was with the earth, which only with difficulty adopted the productions of labor and culture, and which reserved all its tenderness and all its benefits for its own alone: it was a stepmother to some, and a passionate mother to others. The gardener seemed so pleased with this reason that he offered Aesop everything that was in his garden.