The last scientific journal article I wrote as a college professor was about an education exercise I developed that straddled the line between science and science fiction. Here's the abstract:

Nonmajors biology courses are often taught as less detailed versions of the majors courses. There is often a heavy emphasis on memorizing structures and pathways. This approach can result in low engagement of more creative thinkers. In three community college courses I included a two-week capstone project in which students built the biosphere of an Earthlike alien planet. Students first created alien species to fill specific niches, documenting them through life histories and drawings. Then, working in groups, they hierarchically nested their aliens into food webs and linked ecosystems. In the final iteration of the project, they also grouped their species into evolutionary lineages based on the similarity of their drawings. Students were thus able to directly demonstrate their understanding of key concepts of biology without relying on technical jargon.

I based that exercise on a couple of projects. The first was the Contact Consortium's Cultures of the Imagination, a three-day workshop capped by a live role-playing session, embedded in an interdisciplinary academic meeting. I did that meeting a couple of times, hanging out with academics, NASA people, and science fiction authors. Way cool. The other was an online course for teacher trainees. The paper gives much more detail about the similarities and differences between those projects and mine. It's also free, if you care to read it.

Science as Structured Imagination

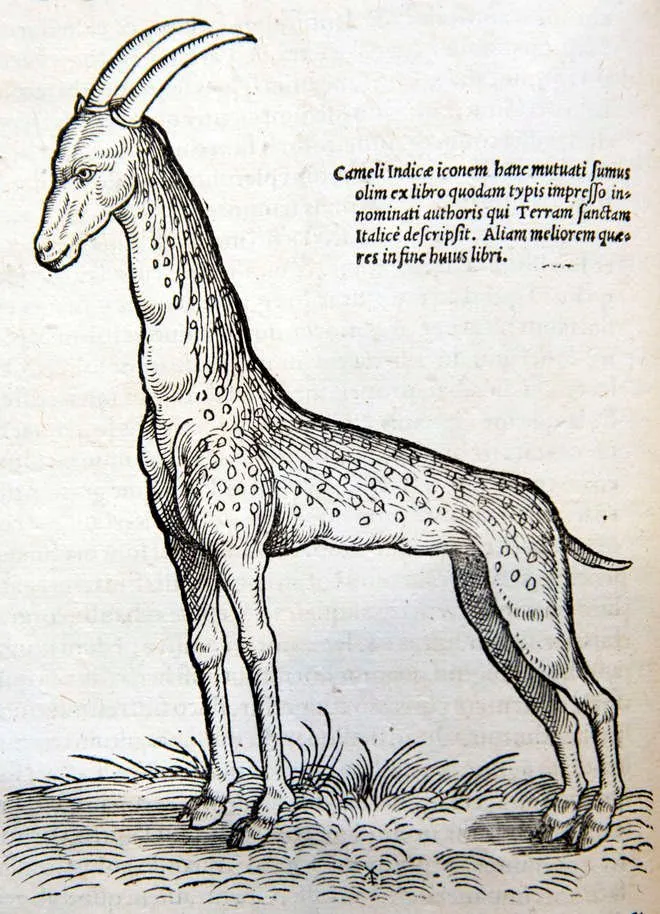

Imagine my surprise, roughly five years later, when I stumbled across this paper, which confirmed something I speculated about in my 2013 paper, that my students weren't necessarily being lazy when their alien creatures ended up being slightly tweaked versions of earth organisms. I suggested that humans think by analogy to what they already know, such as this drawing by Konrad Gessner of an animal he had never seen: the giraffe, or camelopard, which people commonly described as sort of a cross between a camel and a leopard, because it had hooves and a long neck like a camel and spots like a leopard (the horns didn't fit into either analogy, and look more like a goat's horns than the stubby pom-poms on an actual giraffe).

They describe a "seminal" paper from 1994, which I did not include in my paper's references because I had not read it (still haven't).

Ward (1994) asked college students to imagine extra- terrestrial animals. Their creations possessed characteristic attributes of Earth animals, such as sense organs, legs and bilateral symmetry. In one follow-up study (Ward et aI., 2002), subjects were asked to imagine tools that might be used by a highly intelligent species of extraterrestrials, with the following two constraints: the tools are not to be operated by power sources, and the creatures are not to have arms, legs or other appendages comparable to Earth animals. Despite these constraints, most participants relied on typical tools, such as hammers, saws and wrenches that were only slightly modified to allow the creatures to wrap them around their heads or hold them in their mouths. Subsequent interviews with the subjects revealed that a large majority heavily relied on specific examples of ani- mal~ and tools to guide their creative process. The tendency to rely on existing knowledge as a guide to creativity is termed structured imagination (Ward, 1994). This finding has been replicated in many studies, even in children as young as five years of age (Cacciari, Levorato & Cicogna, 1997).

Wow. Almost 20 years earlier, this Ward person had anticipated my idea, and actually done structured experiments, where I was theorizing ad hoc, after observing what my students were doing with their homework. There was a whole field of cognitive science called structured imagination, which I (as a biomedically trained neuroscientist) had totally missed out on. Humbling!

Anyway, this paper goes on to theorize that ALL of our science and technology proceeds this way, through analogies to things that we already know and that we have already invented. We all recognize the baby version of the scientific method, and professionals will nod knowingly at Jorge Cham's satire of it:

Thomas Kuhn famously described an extension of the scientific method, based on what he called scientific revolutions:

In which each stage of his model was composed of many loops of the "normal" scientific method. As I mentioned, Kuhn described many examples of this behavior, but from my admittedly limited readings, Kuhn never really got down to proposing a mechanism for how it worked.

That's what this paper does.

Without ever mentioning Kuhn directly (or citing his work), these authors say that during Kuhn's "normal" science phase, researchers are relying on what they call near analogies, like Niels Bohr's mapping of the orbits of the planets onto the orbits of electrons around an atom's nucleus. During periods of rapid change (Kuhn's "model crisis" or "model revolution" phases), researchers broaden their search spaces and start casting about for more distant analogies, from other fields of science, from the arts, or even from everyday life. Kuhn describes it in more poetic terms

"a proliferation of compelling articulations, the willingness to try anything, the expression of explicit discontent, the recourse to philosophy and to debate over fundamentals"

which are considerably less helpful, imho. "Compelling articulations" could mean pretty much anything.

So check out this paper, which I found considerably more compelling. Here's the abstract:

This paper offers an analysis of scientific creativity based on theoretical models and experimental results of the cognitive sciences. Its core idea is that scientific creativity -like other forms of creativity - is structured and constrained by prior ontological expectations. Analogies provide scientists with a powerful epistemic tool to overcome these constraints. While current research on analo- gies in scientific understanding focuses on near analogies, where target and source domain are close, we argue that distant analogies - where target and source domain differ widely - are especially useful in periods of intense conceptual change. To argue this point, we discuss three case studies from the history of science: early physiologists like Harvey, early evolutionary biologists like Darwin, and recent theorists on the evolution of the human mind like Mithen.

Likewise, a structured way of using analogy could be really helpful to other creative professionals -- SF writers, for instance.

Thanks for reading! I write about science, nature, SF, politics, and occasionally gardening @plotbot2015.

REFERENCES

http://evostudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Hayes_Vol5Iss1.pdf

https://lirias.kuleuven.be/bitstream/123456789/270720/3/DeCruz_DeSmedt_JCB.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/aug/19/thomas-kuhn-structure-scientific-revolutions