Individuals have been approaching it for a large number of years, and it contains all around history.

"It's a beguiling issue since you need to expel it as an idiotic inquiry," says Roy Sorensen, a thinker at Washington University in St. Louis who has composed on the inquiry, "however you can see on reflection that we're anxious with it, yet it's not a dumb inquiry."

To begin with, how about we find the logical solution off the beaten path. Eggs, as a rule, existed before chickens did.

The most seasoned fossils of dinosaur eggs and developing lives are around 190 million years of age. Archaeopteryx fossils, which are the most established by and large acknowledged as feathered creatures, are around 150 million years of age, which implies that winged creatures when all is said in done came after eggs as a rule.

That answer is additionally valid—the egg starts things out—when you limit it down to chickens and the particular eggs from which they develop. Sooner or later, some nearly chicken animal delivered an egg containing a winged creature whose hereditary cosmetics, because of some little change, was completely chicken. Given the incremental idea of hereditary changes, finding that exact isolating line is practically unimaginable, however chickens were tamed, wandering from their wild partners, at some point in the scope of 7,000 years back. Neil deGrasse Tyson has supported this thought of the not-exactly a-chicken winged animal laying the egg which would grow up to be a chicken, and Bill Nye concurred.

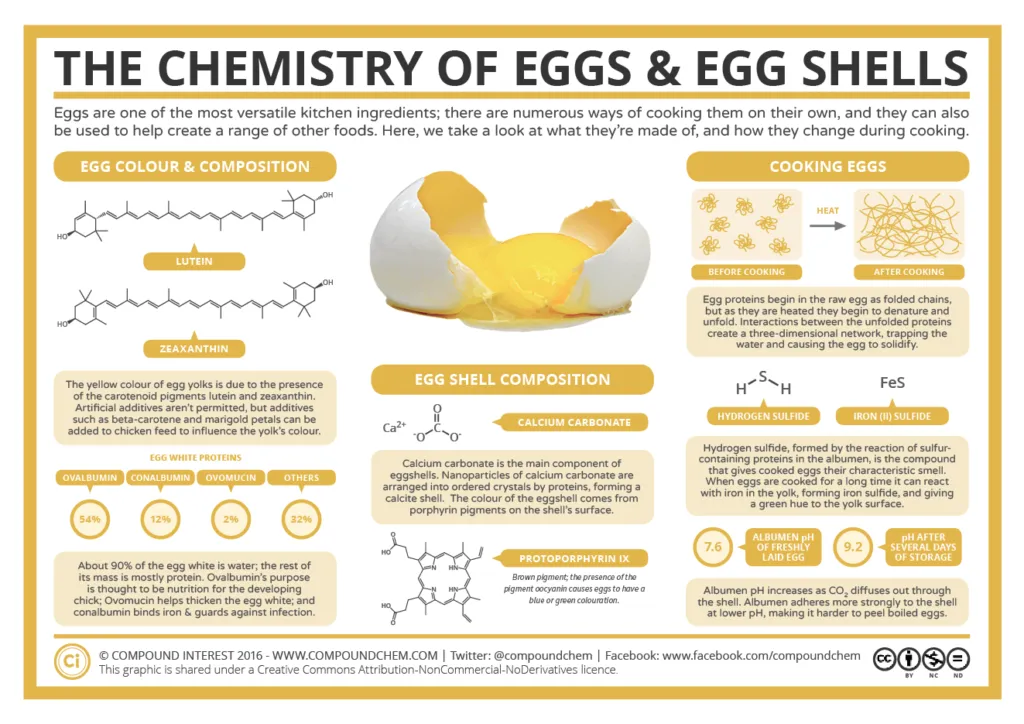

A couple of years back a gathering of researchers wrote about how a specific protein required for chicken egg shell development was just found in chicken ovaries. That information was frequently detailed as proof that the chicken was to start with, yet even the researchers whose review it was weren't excessively persuaded, with one of them calling the inquiry "fun however futile." (When the Oxford English Dictionary gave it a go, investigating which word has a more drawn out history, that technique that yielded no unmistakable answer.)

Maybe the all the more intriguing edge, at that point, is the place the inquiry began—and what its answer's advancement (no play on words expected) uncovers about the historical backdrop of human idea.

The story begins in Ancient Greece. Aristotle was plainly pondering this kind of question, says Sorensen, however he avoided answering it by saying that both went endlessly in reverse and had dependably existed. A 1825 English interpretation of François Fénelon's book on antiquated scholars portrayed Aristotle's point of view: "There couldn't have been a first egg to give a start to winged animals, or there would have been a first flying creature which gave a start to eggs; for a fowl originates from an egg."

It was Plutarch who gave the inquiry its persisting structure, "Regardless of whether the Hen or the Egg Came first," composition of the "little inquiry" that it "shook the considerable and profound issue (whether the world had a start)." In the fifth century, one Roman researcher, Macrobius, composed that individuals "quip about what you assume to be a detail, in asking whether the hen started things out from the egg or the egg from the hen, however the point ought to be viewed as one of significance."

Christian logicians like Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas invested energy considering how to square Greek logicians' ponder and sage reasoning with the assurance of their religious perspective, says Sorensen. All things considered, understanding the inquiry construct entirely in light of Genesis, the chicken would start things out.

A couple of hundred years after the fact, the Italian normal student of history Ulysse Aldrovandi composed quickly on the issue, uncovering that the inquiry was outstanding yet settled in the year 1600: "I ignore now that trite and along these lines slothful as opposed to inquisitive inquiry, regardless of whether the hen exists before the egg or the other way around. It is expressed in the sacrosanct books that the hen existed first. These books show that creatures were made toward the start of the world; consequently the hen did not originate from the egg but rather from nothing."

By the eighteenth century, be that as it may, things were evolving. Denis Diderot, a critical edification scholar and editorial manager of the Encyclopédie, did not see the inquiry as so basic. "On the off chance that the subject of the need of the egg over the chicken or of the chicken over the egg humiliates you, it is on the grounds that you assume that creatures initially were what they are at display," he wrote in 1769. "What habit!" To Diderot, a creature's past was as unverifiable as its future.