In case you haven’t noticed, humans aren’t that great at taking care of our planet. In fact, I’d say we’re terrible at it. Pollution is easy to make, but cleaning it up is the hard part. Many of the environmental issues we face today stem from this fundamental problem and scientists, as always, are working towards a solution.

Today, I’ll be discussing the use of microbes as a cellular machine to clean up pollutants in the environment. This process is known as bioremediation and has been an active area of research for the past 30 years (1). This field has already yielded useful applications as there are numerous examples of using microbes to help deal with pollutants like heavy metals, oil spills, radiation, and more at contaminated sites. However, the recent availability in metagenomic sequencing (2) and advanced genetic tools (3), the potential for bioremediation has never been greater.

Why use microbes?

Pollution-cleaning microbes have many advantages over traditional environmental cleanup. Tiny organisms can infiltrate contaminated sites that would otherwise be difficult to access (4). For example, bacteria can be dumped into soil to treat groundwater beneath the earth’s surface which would otherwise require an expensive excavation or pumping operation. Bioremediators can usually survive and even reproduce in a contaminated environment which means that they may only need to be added once and will continue to decontaminate the site for a long time.

Bioremediation has always held a lot of promise because of the immense variety of microbes on earth. Bacteria and other small organisms have evolved to fill every niche on this planet. As a result, as least one microbe has figured out how to metabolize or remove almost any naturally occurring pollutant (and even some unnatural ones). Scientists want to harness these naturally evolved abilities or enhance them with genetic engineering (2, 3). Currently, the main goal of most bioremediation research is to find or create a stain that can easily degrade or remove a specific pollutant from a contaminated site.

Bioremediation in Action

I’ve decided to focus on a paper that identifies a viable candidate for bioremediation and shows its effectiveness in action. This paper by Jeong ock Joo et al. is titled “Effective Bioremediation of Cadmium (II), Nickel (II), and Chromium (VI) in a Marine Environment by Using Desulfovibrio desulfuricans” (5). In this paper, the authors start by identifying the problem: heavy metal contamination in seawater. Heavy metals are a major hazard to humans because they can accumulate in the body and cause serious health problems. This is not to be confused with heavy metal, a genre of music that is relatively benign unless its applied directly to the eardrums.

Heavy metals enter the ocean through river runoff, industry waste, or just plain garbage (Source).

The focus on seawater is important to keep in mind. Previous work has identified bacteria that can remove heavy metals from freshwater (6), but these bacteria wouldn’t be able to survive in the ocean. The authors needed to find an organism that could survive the lower oxygen levels, reduced sunlight, and higher salt content of typical seawater.

1.) It can survive in the ocean

2.) Sulfate reducing bacteria can metabolize heavy metals

3.) This species is well-studied

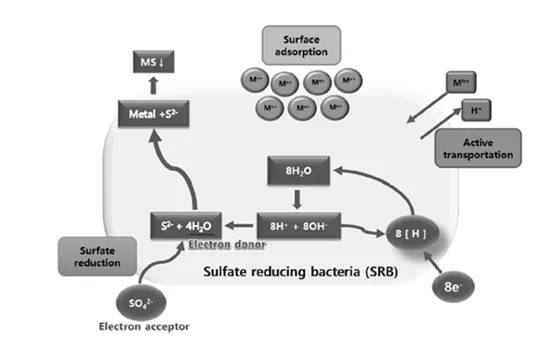

Some relevant background information - sulfate is a simple sulfur compound (SO4) that some bacteria can reduce for energy. The removal of heavy metals is a byproduct of sulfate reduction. This process produces sulfides which readily combine with heavy metals and become an insoluble precipitate. The image on the right shows this process in more detail. The sulfate (SO4, bottom left corner) and metal ions (M) enter the cell the metal sulfide (MS, top left corner) precipitates out.

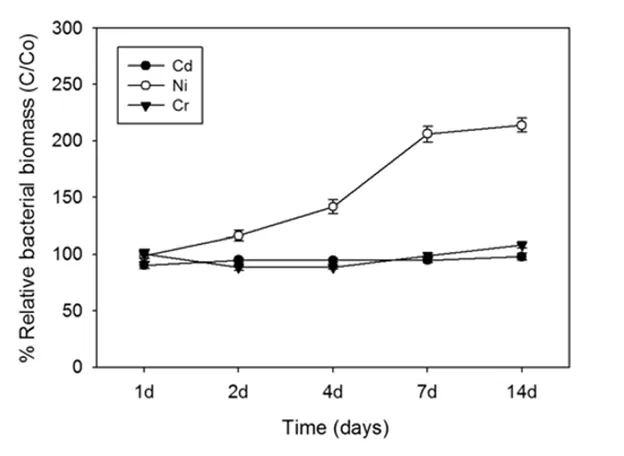

However, just because these bacteria can remove these heavy metals doesn’t mean that they can survive them. Heavy metals can be just as detrimental to bacteria as they are to humans, and the authors first had to confirm that Desulfovibrio desulfuricans could survive in seawater containing heavy metals.

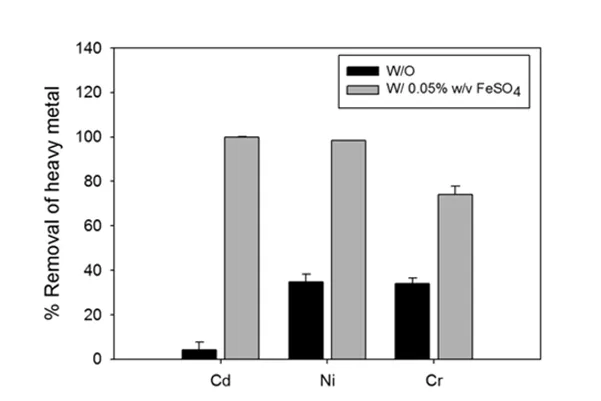

Figure 2: Removal of heavy metals using Desulfovibrio desulfuricans, in the presence and absence of FeSO4 in artificial seawater.

As you can see in the figure above, all of the cadmium (Ca), all of the nickel (Ni), and most of the chromium (Cr) were removed from the seawater as long as a sulfate source was present. The bacteria were still able to remove some of the heavy metals in the absence of iron sulfate, probably because small amounts of residual sulfate were available for reduction.

At any rate, these two figures are the main crux of the paper. They show that Desulfovibrio desulfuricans can survive in heavy metal contaminated seawater and can remove the heavy metals from the media. The subsequent experiments the authors perform further defined this function. They show that this activity is faster at higher temperatures (up to 37 degrees Celsius) and is very effective up to a heavy metal concentration of 100 parts per million and becomes less effective at higher concentrations.

Thus, the authors have identified a viable candidate for bioremediation of seawater containing heavy metals. This doesn’t mean they’ll just start dumping Desulfovibrio desulfuricans into the ocean and hoping for the best. At best, this bacterium might be added to contained contaminated sites (like wastewater tanks in factories near the ocean) to test for effectiveness in a real-world situation. Further research may even try to improve this strain to make it a more efficient bioremediator.

Keep in mind, this paper represents a single step among many that the scientific community are taking to save the earth. Other groups are working with different species, locales, and contaminants. Ideally, each success gives us one more tool to combat pollution and will hopefully help make saving the earth a surmountable task.

Images

All images used have been labelled for re-use on Google Images or are taken directly from the publication. If any image owner has an issue with this article, please contact me and I will address the issue.

Sources

(1) https://www.osti.gov/scitech/biblio/5558083

(2) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27558781

(3) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28789939

(4) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bioremediation

(5) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12257-015-0287-6

(6) http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213343713000249

About the Author

I’m a a research scientist living in the suburbs of Boston. I recently left academia to work in in industry, but I miss teaching so I decided to start writing articles on interesting discoveries in the world of microbiology. My goal is to uncover subjects that are unusual, unique, and might one day have a major impact on our daily lives.