Introduction

The idea of a “Deep State” is nothing new to students of politics; one of the earliest discussions can be found in Bagehot’s 1867 Theory of Dual Institutions; Glennon (2014) discusses the theory as describing “dual institutions of governance, one public and the other concealed, evolve side-by-side to maximize both legitimacy and efficiency.” Modern usage of the term “Deep State” is first associated with Turkish security agencies in the 1990s, while Glennon focuses on the issue within the United States. And while a great deal of public discussion of such “Double Governments” has been in the nature of conspiracy theory, there is a body of academic work that discusses these “Deep States” as political reality. It must be emphasized that the scope of this study addresses neither the actual existence of a “Deep State” in American government nor the validity of any of the accusations made in the “Spygate” scandal. Rather, it focuses on how the public perception of these events may affect IC capability.

Americans have a government that is legally constituted to be driven by the citizens of the country through a voting process, establishing legitimacy...whether any form of governance can be seen as “efficient”, however, is the subject for another study. This study addresses the possibility of a “Deep State” in American government, and whether public perception of any such “Deep State” as revealed through the “Spygate” controversy can hinder the Intelligence Community (IC) in the performance of it’s mission to defend the United States.

“Americans have never been entirely comfortable with the existence of a permanent intelligence bureaucracy. A common narrative is that a secretive government runs counter to the ideals of democracy and liberty upon which the United States was founded. “(“The Intelligence Community Should Build Public Trust, Not Just Transparency,” 2015). Public distrust in the IC in the past has resulted in hindrances to successfully accomplishing IC duties, as Powers (2004a, 2004b) points out.

Therefore, considering that there is established existence of “Deep State” institutions in other governments, and there is is a current political dispute involving the possibility of such an institution involving the IC in interfering with the legitimate political process, it behooves us to examine how public perception of such action may lead to future disruption of the IC mission.

A potential issue with this question is that it is inherently political; controversy over the legality of actions taken by the DNI, DNC, FBI and NSD of the DOJ is still debated, including the existence of a “Deep State” itself. The discussion in this case study does not take a position on these question, but rather asks how public perception of the controversy can affect the ability of the IC to protect America.

Hypothesis

The base hypothesis of this qualitative study is that public perception of, and therefore public trust in the IC can be negatively impacted the appearance of illegal or unethical actions by members of the IC. Considerations that will be examined will be public documentation of such acts, polling data, and a review of bias in the sources.

Literature Review

This literature review will establish a contextual background for asking the question, Does the appearance of, not necessarily the existence of, a “Deep State” based conspiracy linked to the “Spygate” political controversy, hinder the Intelligence Community (IC) in the performance of it’s mission to defend the United States.

The review will address several concepts that are central to the question. The first is the theoretical framework of Kellers’ “Liberal Theory of Internal Security” and how it applies to the organization and purpose of the American IC as it organized for domestic (currently known as “Homeland”) security. The second is the established academic concept of a “Deep State” entity as a matter of general politics. A third idea of note is the effect of politics and corruption on the IC mission. Following this is the fourth concept of public control of the IC and how that is accomplished in a republic. The fifth and final element is a discussion of how to measure public reaction to the “Spygate” controversy. The final element will also require further discussion of bias in public polling.

Theoretical Framework

The basic purpose of the IC is to protect the United States. How this is done can always bring disagreement.

Although Bagehot was the first to discuss the “Deep State” model, it has also been studied in relation to countries like Turkey (Kaya, 2009), and there is currently security study of the silovki of Russia ( if not academic). Tas (2014) highlights there is little study that has been done on “Deep State” concepts, although Ganser (2016) explains Söyler's argument “that the presence of the deep state within a particular state structure can be measured through certain quantifiable criteria.” Kaya does bring up an underlying theory of rent-seeking proposed by Mancur Olson (theory of distributional coalitions): “Olson’s theory holds that rent-seeking (or special interest) groups tend to be exclusive by nature and pursue only the interests of their own members.” Glennon (2014) focuses the discussion on American government.

Another theory that has some bearing is Loewenstein’s “Militant Democracy”, in which he warns of one-party domination of state apparati.

Yet, none of these theories completely describes the American situation. This is a situation which Americans have grappled with before, and that Keller (1989) attempted to explain with “the Liberal Theory of Internal Security”. O’Reilly (1982) demonstrates how this attitude was put into this place as Roosevelt authorized the FBI to take the initiative against domestic threats. Keller’s theory claims that “liberalism was an approach to internal security that supported delegation of authority to a strong central domestic agency”. Keller lays this out in terms of security agency autonomy versus political authority. Keller describes the background of his theory as liberals felt that both extremes of Left and Right presented danger to America, and that there were three “pillars” of the theory.

• That wide investigatory power was bestowed upon the FBI to deal with these threats by delegation of Executive power.

• That “prevention” of sabotage or sedition was also delegated to the FBI.

• That the level of intelligence operations be related to emergency conditions.

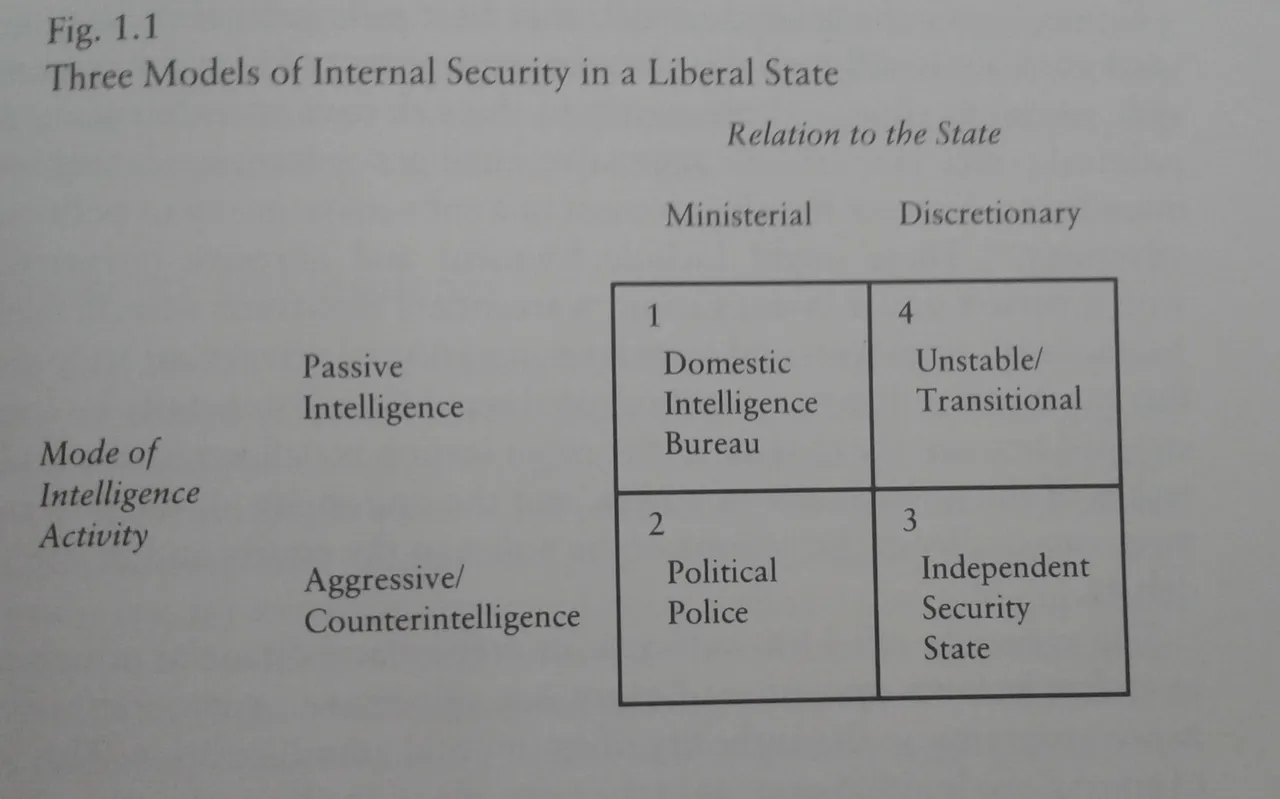

Keller sets a matrix of nodes of “Mode of Intelligence” (Passive Intelligence - Aggressive/Counterintelligence) against nodes of “Relation to the State” (Minsterial – Discretionary) to define domestic intelligence agency models, which results in 3 models (Keller claims that the result of the “Passive Intelligence” and “Discretionary” nodes is unstable and tends towards the “Independent Security State” model.

Figure 1: (Keller, 1989)

Keller also provides a transition to the second concept, as he discusses the Prussian Army as a “state within the state” in pre-WW1 Germany.

The concept of a Deep State in relation to the issue

It is necessary to examine the idea of a “Deep State” in context of understanding how the public reacts to this particular controversy, as the explanation for the perceived corruption lies in the belief that such a conspiracy exists. The concept of a “double state” has been studied since Bagehot’s 1867 Theory of Dual Institutions . Glennon (2016) suggests that such a “double government” does exist within the national security structure of the United States. Söyler argues that ”Deep State” entities can be measured by objective criteria. Unfortunately, as Tas (2014) notes, there is little study that has been done on modern “Deep State” concepts. However, the existence of such studies, or of a “Deep State” itself, is secondary to the issue of how the public perceives a “Deep State threat”. This discussion is included to understand why some in the public would hold to such a theory to explain the controversy.

How has politics and malfeasance created public demand for action regarding the intelligence community in the past?

Intelligence failures or scandals such as in the cases of Pearl Harbor, the 9/11 attacks, or the domestic spying abuses of the early 70s which led to the Church Committee, have initiated American citizens to demand reform of the IC from the government.

Similar scandals to “Spygate” have caused great damage to the IC’s ability to defend the nation in their wake. Johnson (2004) claims that revelations of abuse generated “a firestorm of public outrage”; in addition Johnson argues the reforms had a postitive effect. However, Codevilla, who served on the Church Committee, in a 2019 interview with Samuels, argues that the Church Committee was an operation between ‘the left’ inside the intelligence community, and allies on the Hill” which left the Left in control of the CIA. Loewenstein (1937a, 1937b) escaped Nazi Germany to warn of a sole political party in control of all aspects of government function. Powers (2004a, 2004b) goes into detail on how the changes wrought by the Committee affected the ability of the IC to do it’s job.

Public control of the IC, and the need for trust

In the American republic, control over the IC is legally defined via the Constitution, with an understanding that competing influences would stalemate each other in the checks and balances of three separate branches of government (Van Puyvelde, 2013). Bypassing Loewenstein’s concerns for the moment, these formal structures reflect IC management's understanding of the need to maintain public trust.

The core principles of protecting privacy and civil liberties in our work and of providing appropriate transparency about our work, both internally and to the public, must be integrated into the IC’s programs and activities. Doing so is necessary to earn and retain public trust in the IC, which directly impacts IC authorities, capabilities, and resources. Mission success depends on the IC’s commitment to these core principles (Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2019)

McCubbins and Schwartz(1984) discuss the “fire alarm” model in relation to Congressional oversight. In this model, legislators respond to citizen demands on the basis of re-election, focusing their attention on special interest groups “and, to a lesser extent, concerned citizens“. Zegart and Quinn (2010) apply this model in relation to intelligence oversight. Eliff (1979) address these issues in the aftermath of the Church Committee reforms of the FBI.

However, Zegart and Quinn (2010) do note that the public is largely apathetic to intelligence policy, and Van Puyvelde (2013) reinforces their contention that IC policy is largely driven politically by special interests rather than the public in general.

Understanding that the method for determining public reaction is itself a mode of contention

de Vries (2012) refers to James Lull and Stephen Hinerman who argue that “the most important criterion for the definition of ‘media scandal’ is the involvement of the public”. Because the method for understanding public perception and reaction to the “Spygate” controversy will be measured in polling data, it is necessary to understand the problems inherent in political (and to a lesser degree, any other) polling methods. Polling is conducted under the banner of the media industry, and partially directed under the leadership and/or advice of the academic industry. Sutter (2012) explains the bias in both industries. Groseclose, T., & Milyo (2005) point out that discussion of media bias is itself a subject of partisan debate. Baron (2006) points out that the public tends to view the media as biased. While Matei (2014) suggests that the media plays an important part in informing the public as a watchdog on government abuse of intelligence (keeping in mind this requires an unbiased media), The Hill notes that most Americans don’t believe the polls that the media presents them (Sheffield, 2018). And Mueller and Stewart (2011) note that public response to (and media coverage of) the Fort Hood terror attack was “muted”.

Research Design

The purpose of this qualitative study is to determine how Intelligence Community (IC) malfeasance, or simply it’s appearance, affects the public support that the IC requires in order to fulfill it’s duty to the country. This study will address several concepts that are central to the question. The first is the theoretical framework of Kellers’ “Liberal Theory of Internal Security” and how it applies to the organization and purpose of the IC as it organized for domestic (currently known as “Homeland”) security. The second is the concept of a “Deep State”, first discussed by Söyler in relation to Turkey (Ganser, 2016), and how this concept can explain some public mistrust and conspiratorial thinking. A third idea of note is the effect of politics and corruption on the IC mission. Following this is the fourth concept of public control of the IC and how that is accomplished in a republic. The fifth and final element is a discussion of public reaction to the “Spygate” Controversy.

The discussion on the first four elements is based upon literature review in order to understand these elements in relation to each other and provide a foundation for discussion of the fifth. Data for the fifth element will be based upon government documents that are publicly available in regards to controversy over malfeasance, while polling surveys will provide an overview of public perception of, and reaction to, the issue. The basis for public perception are government investigations and media reports of those investigations. To avoid the issues of media bias discussed in the literature review, sources will be limited to government documentation (and keeping in mind that such reports are produced by men with their own, or institutional biases), and by necessity, polls undertaken by the media with a short note on possible bias.

Potential Issues

There are two potential issues with this type of study, both concerning bias. The first is that as a qualitative study in a fundamentally political controversy, sources are likely to be biased. This requires an understanding of source origination. The second is that author bias may determine which sources are included, aka “cherry picking” data.

Analysis and Findings

Government Reports

The DOJ OIG has referred both James Comey and Andrew McCabe for criminal prosecution for actions related to “Spygate”.(U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General, 2018a) (U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General, 2019). Another OIG report (2019b) consisting of over 500 descriptive pages of actions taken by the FBI that were characterized as “inconsistent with typical investigative strategy.” This leads to a foundation for political suspicions.

Poll Findings

An example of the political dispute can be seen in polls regarding the controversy. In a poll conducted by the Texas National Security Network at the University of Texas at Austin (“Annual Polling Confirms Sustained Public Confidence in U.S. Intelligence,” 2019), the group found that “most Americans, including Republicans, continue to express confidence in the intelligence community.” Yet a poll conducted by Rasmussen (“Most GOP Voters Say Feds Very Likely Broke the Law To Stop Trump—Rasmussen Reports,” 2018) found that “Most Republicans are now convinced that high-level federal law enforcement officials tried illegally to stop Donald Trump from being president.” Certainly, Americans want the matter investigated fully, as “Sixty-two percent of respondents to the May 17-18 survey said they support Attorney General William Barr's decision to name a U.S. attorney to determine whether law enforcement officers had obeyed regulations governing surveillance of U.S. citizens while 38 percent said they opposed the new inquiry” (Sheffield, 2019).

Bias in such polls will need to be accounted for. Lawfare is accused of being a consortium of legal support for the Deep State by “Sundance”, the writer of a conservative blog, The Last Refuge, which has tracked the controversy with it’s own bias. Silver (2010) defended Rasmussen from charges of bias. The Hill tends to lean liberal on domestic affairs, but it’s coverage of “Spygate” from the conservative John Solomon have led to accusations of conservative bias.

All three polls do reflect a high level of division in perception. Is there, however, enough of a public reaction to cause backlash to the IC? It doesn’t appear so at this point in time.

Conclusions

The defense of any nation requires some amount of secrecy to accomplish intelligence goals. The amount of secrecy, autonomy, and Constitutional control of intelligence agencies plays a part in defining how those agencies operate for the IC of the United States. Nominally, the public controls the management of these agencies through the electoral process, and the media plays a part in informing the public as much as possible. However, this process requires an unbiased media that is not in alliance with a political party (such alliances coming close to the vision of tyranny that Loewenstein presents). Public trust in the governance of intelligence is necessary, and when the public (or special interests) gets “outraged” at abuses, or perceived abuses of the IC, the demands for reform can result in hindrances to the ability of the IC to defend America. And there is the possibility, considering the arguments made in the literature, that public perception of the “Spygate” controversy will generate no response demanding government reform.

Keller’s theory may be applied to the concept of an American “Deep State” and potential “Spygate” violations in conjunction with with the theoretical descriptions of a rent-seeking “Shadow Government” and the possibility of political alignment counter to the defense of the American Republic. If the American public were to suspect the IC (or elements therein) were suborning the legal process, the restrictions on policy, demands for unreasonable transparency, and budgetary withholding could prove devastating to the IC’s job of keeping America safe.

While this paper does not take a position on the existence of a “Deep State”, understanding the concept allows a broader vision of how the public may view such a conspiracy could play a part in alleged “Spygate” abuses, and thus how deep the resulting reform process may go.

REFERENCES:

Annual polling confirms sustained public confidence in U.S. intelligence. (2019, July 10). Retrieved October 17, 2019, from Lawfare website: https://www.lawfareblog.com/annual-polling- confirms-sustained-public-confidence-us-intelligence

Bagehot, W. (1867). The English Constitution. London: Chapman & Hall.

Baron, D. P. (2006). Persistent media bias. Journal of Public Economics, 90(1–2), 1–36. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.10.006

de Vries, T. (2012). The 1967 Central Intelligence Agency Scandal: Catalyst in a Transforming Relationship between State and People. Journal of American History, 98(4), 1075–1092. https:// doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jar563

Elliff, J. (1979). The reform of FBI intelligence operations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Glennon, M. J. (2014). National security and double government. Harvard National Security Journal, 5(1), 1–113.

Groseclose, T., & Milyo, J. (2005). A Social-Science Perspective on Media Bias. Critical Review, 17(3/4), 305–314.

Kaptan, S. (2016). The Turkish Deep State: State consolidation, civil-military relations and democracy. New Perspectives on Turkey; Istanbul, 54, 148–151.

Kaya, S. (2009). The rise and decline of the Turkish “Deep State”: The Ergenekon Case. Insight Turkey, 11(4).

Keller, W. W. (1989). The liberals and J. Edgar Hoover: Rise and fall of a domestic intelligence state. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Loewenstein, K. (1937a). Militant democracy and fundamental Rights, I. The American Political Science Review, 31(3), 417. https://doi.org/10.2307/1948164

Loewenstein, K. (1937b). Militant democracy and fundamental Rights, II. The American Political Science Review, 31(4), 638. https://doi.org/10.2307/1948103

Johnson, L. K. (2004). Congressional Supervision of America’s Secret Agencies: The Experience and Legacy of the Church Committee. Public Administration Review; Washington, 64(1), 3–14.

McCubbins, M. D., & Schwartz, T. (1984). Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms. American Journal of Political Science, 28(1), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/2110792

Matei, F. C. (2014). The Media’s Role in Intelligence Democratization. International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 27(1), 73–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2014.842806

Most GOP voters say Feds very likely broke the law to stop Trump—Rasmussen Reports. (2018, May 24). Retrieved October 17, 2019, from http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/general_politics/may_2018/ most_gop_voters_say_feds_very_likely_broke_the_law_to_stop_trump

Mueller, J., & Stewart, M. G. (2011). Balancing the Risks, Benefits, and Costs of Homeland Security. Homeland Security Affairs; Monterey, 7(1).

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2019). The National Intelligence Strategy of the United States of America. Retrieved from https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/National_Intelligence_Strategy_2019.pdf

Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: Economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. Retrieved from http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/apus/detail.action?docID=3420903

O’Reilly, K. (1982). A New Deal for the FBI: The Roosevelt Administration, crime control, and national security. The Journal of American History, 69(3), 638–658. http://doi.org/10.2307/1903141

Powers, R. G. (2004a). A Bomb with a LONG FUSE: 9/11 and the FBI “reforms” of the 1970s. American History, 39(5), 42–47.

Powers, R. G. (2004b, November). Stunned Guns. The Washington Monthly, 36(11), 37–43.

Samuels, D. (2019, October 24). The Codevilla Tapes. Retrieved October 25, 2019, from Tablet Magazine website: https://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-arts-and-culture/culture-news/292763/ angelo-codevilla

Sheffield, M. (2018, December 27). Survey: A majority of Americans don’t believe polls are accurate [Text]. Retrieved November 9, 2019, from TheHill website: https://thehill.com/hilltv/what- americas-thinking/423023-a-majority-of-americans-are-skeptical-that-public-opinion-polls

Sheffield, M. (2019, May 21). Most Americans support inquiry into FBI decisions to monitor former Trump campaign officials: Poll [Text]. Retrieved November 30, 2019, from TheHill website: https://thehill.com/hilltv/what-americas-thinking/444799-most-americans-support-inquiry-into- fbi-decisions-to-monitor

Silver, N. (2010 January 1). "Is Rasmussen Reports Biased?". The New York Times.

Söyler, M. (2015.) The Turkish Deep State: State Consolidation, Civil-Military Relations and Democracy. New York: Routledge

Sutter, D. (2012). Mechanisms of Liberal Bias in the News Media versus the Academy. The Independent Review, 16(3), 399–415.

Tas, H. (2014). Turkey’s Ergenekon imbroglio and academia’s apathy. Insight Turkey; Ankara, 16(1), 163–179.

The Intelligence Community should build public trust, not just transparency. (2015, July 21). Retrieved October 17, 2019, from Overt Action website: http://www.overtaction.org/2015/07/the- intelligence-community-should-build-public-trust-not-just-transparency/

U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General. (2018a). A Report of Investigation of Certain Allegations Relating to Former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe. Retrieved from https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2018/o20180413.pdf

U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General. (2018b). A Review of Various Actions by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Justice in Advance of the 2016 Election Oversight and Review Division. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/file/1071991/download

U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General. (2019). Report of Investigation of Former Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey’s Disclosure of Sensitive Investigative Information and Handling of Certain Memoranda (p. 83). Retrieved from https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2019/o1902.pdf

Van Puyvelde, D. (2013). Intelligence Accountability and the Role of Public Interest Groups in the United States. Intelligence and National Security, 28(2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2012.735078

Zegart, A., & Quinn, J. (2010). Congressional Intelligence Oversight: The Electoral Disconnection. Intelligence & National Security, 25(6), 744–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2010.537871