Inspired by a topic in the #steemstem chat, I was thinking about how feelings can have an impact on scientific research. And as an Egyptologist, I am often asked how we discover new archaeological sites. Is it a "feeling" of "something" that could be buried somewhere, like when Howard Carter broke accidentally into the tomb of Tutankhamun when his horse stumbled upon a doorway that was hidden under the sand - as the legend tells us?

And how can we draw our conclusions after we discovered new artefacts at an archaeological site in Egypt? Today I want to show you a few main principles of our work that can also be adapted to scientific research in general. But Egyptology is very often flanked by pseudo-scientists who claim to have found solutions to unsolved problems of Archaeology without providing any basic scientific proof. I am far away from presuming those people to have bad intentions. Quite the reverse! From my perspective, we as Egyptologists can learn a lot from them since many of us got a bit conservative over time and tend to cement our opinions due to many reasons. But yes - sometimes we too have a „certain feeling“…

Analyzing the feeling

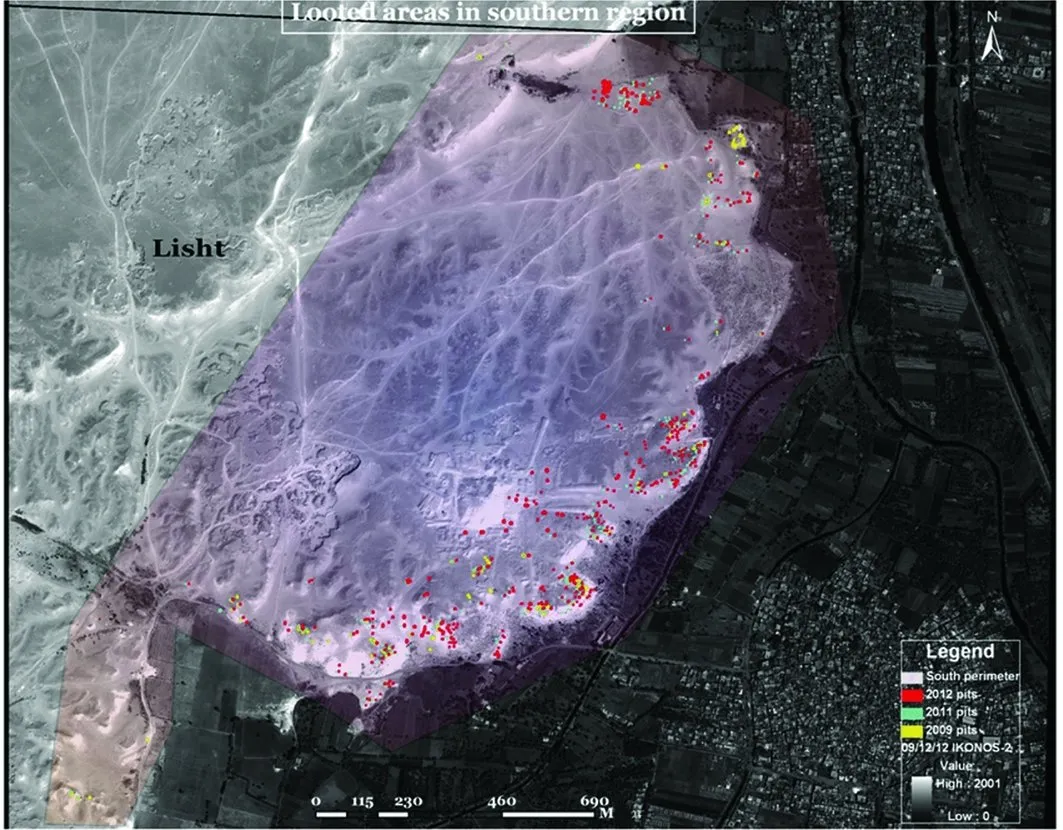

There are many ways to discover new places with ancient Egyptian artefacts. As for Archaeology, in general, I can refer to the 3 articles of my colleague @zest who provided already a profound summary of how to find „your own archaeological site“: Part 1, Part 2,Part 3. I can only add that there is also „satellite archaeology“ in Egypt (and elsewhere) that is used not only to discover new burial sites or similar but to find areas where cultural heritage is being destroyed by tomb robbers.

Feelings can be the initial ignition for starting a research, but in most cases, they are not coming „out of the blue“. From a scientific perspective, they are based on experience in that special area. For further reading, I can recommend an article of Panos D. Bardis regarding scientific methods (see endnote 1). Intuition plays also a big role for Egyptologists. But it is based on knowledge and continuous study in the field and the library. So, the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun didn’t come by chance. It was the result of an intensive research Howard Carter did on the placement, architectural structure and other parameters of the surrounding tombs.

When people without an academic background get a special feeling of „how it could have been“ in Ancient Egypt, so is this actually a positive thing. It only means that they are starting from a different point of view. In general, many people have a huge knowledge about Ancient Egypt, not only because there are a lot of documentaries on TV but because of an immense interest of in the heritage of humankind. We should not underestimate that they could have this intuitive perspective, that scientists sometimes lack, and that could lead us to an unusual or unexpected result. But in most cases, people fail to make their research visible, comprehensible and traceable to others. At least they should cite their sources - even if it is the „infamous“ Wikipedia. Respecting the principles of science are the basis of a mutual understanding between academic and non-academic researchers.

Egyptologists do experiments too

Biologists, Physicists and Chemists are directly perceived as „scientists“ because they used to work in laboratories, doing experiments and writing protocols. Egyptologists are often only seen as „Dreamers playing in the sand“. ;) But we also do experiments. It is called „Experimental Archaeology“.

This is a collection of images from an experiment in my study on ancient egyptian medical recipes of Papyrus Hearst against constipation to find out how this medicine was made and how it worked. We tried to use only materials that were available in that time and imitated the preparation of the ingredients in the same way. We found out that they used a special linen fabric for filtering a cooked mixture of ancient wheat. The fabric had not only an influence on the viscosity of the mixture but we assumed after, that probably not the mash of grains had to be eaten but the extracted water had to be drunken in order to stimulate digestion.

This is a collection of images from an experiment in my study on ancient egyptian medical recipes of Papyrus Hearst against constipation to find out how this medicine was made and how it worked. We tried to use only materials that were available in that time and imitated the preparation of the ingredients in the same way. We found out that they used a special linen fabric for filtering a cooked mixture of ancient wheat. The fabric had not only an influence on the viscosity of the mixture but we assumed after, that probably not the mash of grains had to be eaten but the extracted water had to be drunken in order to stimulate digestion.Furthermore, our principles of research are almost the same as everywhere:

- identifying a problem

- developing a scientific question

- describing the issues and the methods

- collecting data

- analysing and comparing them with the initial question

- and then verify or discard your hypothesis.

(See also the great article of @fabulousfungi.)

The last one, namely to throw over your idea, is the most complicated because no one can easily admit that he or she was wrong. I can remember that I did once a very intense research on only one hieroglyph for over 8 weeks. I wanted to prove that there is a special meaning in the the writing direction of the boat-hieroglyph 𓊛 and 𓊜 (flipped boat), regarding the position of the paddle. But my hypothesis that the hieroglyph symbolizes not only a back-and-forth moving but also a moving-around in a circle according to the sun cycle – could unfortunately not be verified. At least not with the material that I used. I had only old photographs of papyri, stone inscriptions and handwritten facsimiles of the 19th century that contained a lot of mistakes. So, at this stage, I had to put this idea away until I will have access to the original material.

Archaeological fieldwork – theory meets practice

This leads me to another important point. I have a lot of colleagues who never worked in Egypt in their entire life. Some of them even never visited this country. From my perspective, they limit their research to what is already written in the books. Of course, they can do - they build a synthesis between argument 1 and argument 2, which is a normal procedure. But being an Archaeologist in Egypt you need to feel Egypt: you will probably never experience the meaning of the sun cult of RA when you never felt the burning of the heat on your forehead while smelling the dust of the desert or seeing the sparkling of the Nile when you look down from a pyramid-like hill. You need to observe native Egyptians of today because many of their habits, for instance in handcrafting or cooking can be traced back to their ancient ancestors. You have to listen to their stories, even if they consist of 99% fantasy. This 1% you perceive by reading between the lines could be the key to find an answer to an open question. So Egyptology has a lot to do with feelings, but more with empathy and the ability to combine inner and outer elements.

Or as Harrison Ford aka Indiana Jones once said: „If you want to be a good archaeologist, you gotta get out of the library!“ ;)

Sources/Endnotes: Image used in the editorial picture:

1 Panos D. Bardis, Science and Its Method, in: Social Science, Vol. 56, No. 4 (AUTUMN 1981), pp. 226-246. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41886698

2 Satellite remote sensing in Egyptology: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/satellite-evidence-of-archaeological-site-looting-in-egypt-20022013/D23EA939FC4767D8BF50CAC6DE96D005/core-reader#

3 Papyrus Hearst: http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library/tebtunis-papyri/hearst-papyrus

Source

If you liked this article, please follow me on my blog @laylahsophia. I am a german Egyptologist and write about ancient and contemporary Egypt, history of science, philosophy and life.