We probably take it for granted, but it makes sure we don't take injuries and harmful stimulus for granted. It makes us aware of the danger. However, what is this pain sensing machinery in the skin? How does it look like? How does it function?

Illustrated by @scienceblocks using the following images -

Mouse 1 and Pin by Clker-Free-Vector-Images.

Jumping mouse by mohamed_hassan.

Pixabay

The paper

The paper for discussion today is titled - Specialized cutaneous Schwann cells

initiate pain sensation. It is published in Science, by Abdo et al., form Patrik Ernfors' lab at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. In this paper, authors provide evidence for the existence of new pain-sensing organ in the skin.

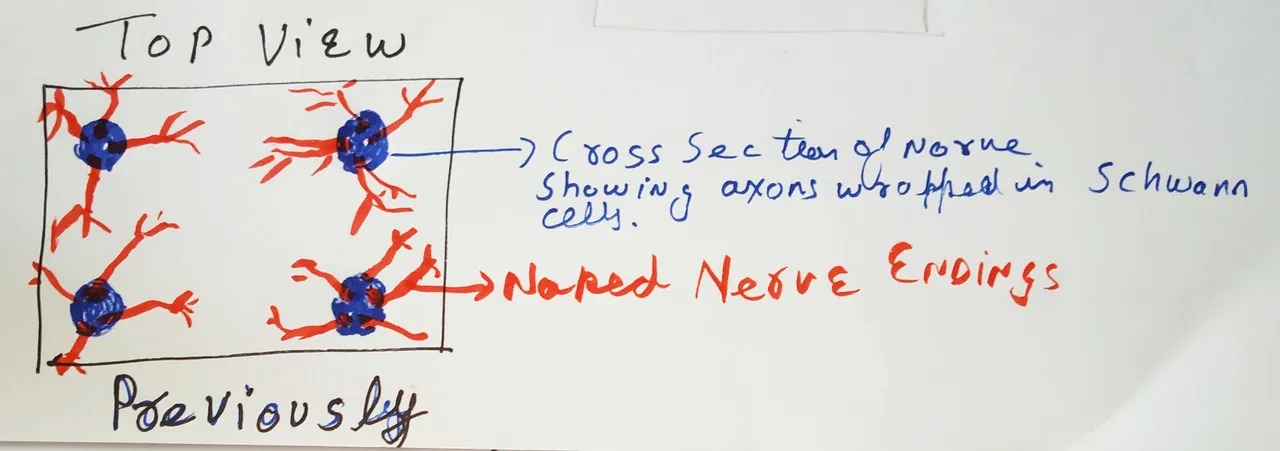

What we thought the pain-sensing machinery looked like.

Skin, is the external barrier of our body. It protects our insides from harmful pathogens, chemicals and basically any direct exposure to the outside world. But because of this prime location, it's also exposed to all kinds of insults - mechanical, chemical, heat and cold. If any of this stimulus is beyond a certain threshold, the skin has the machinery to incite pain. It is a signal for danger, that makes you withdraw from whatever is causing the pain.

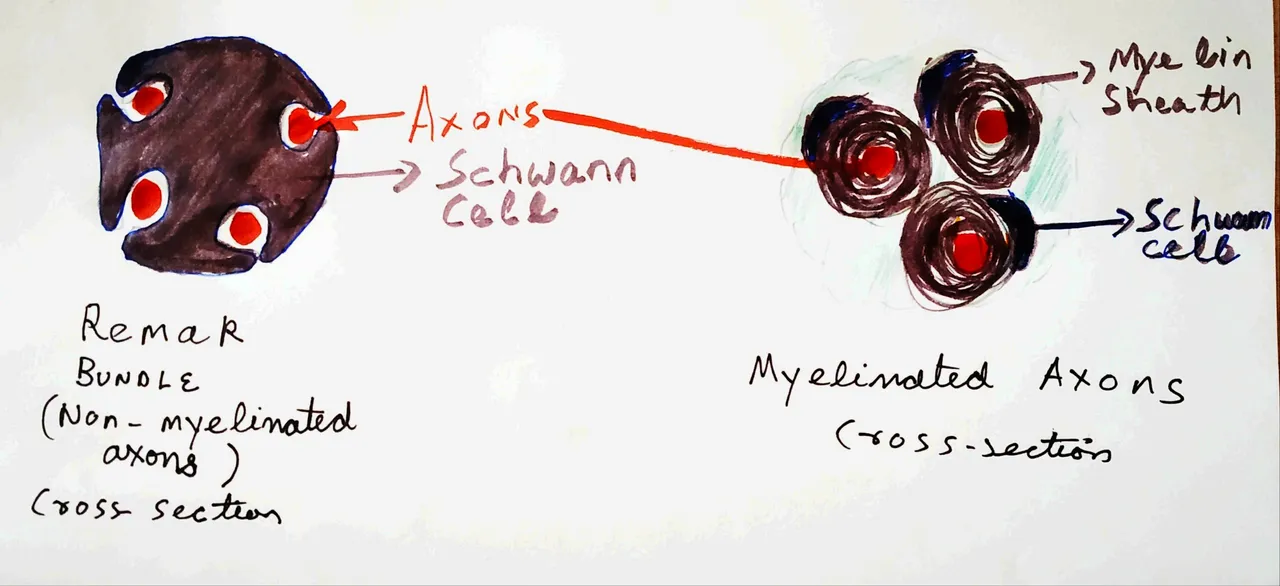

Drawn by @scienceblocks. Inspired by EM images of nerve bundles (see Griffin and Thompson, 2008 and Tao et al., 2009).

What is this machinery made of? Well, there are definitely nerves out there. Nerves extending out of our spinal cord and then terminating into the skin. If you were wondering what nerves are made of - well, they are a bundle of axons. The neuronal cells have 3 parts - the cell body (this is where the nucleus of the cells is), dendrites and these long processes called axons. The sensory nerves which sense pain innervate the skin with their axonal terminals. These terminals are known to sense different stimulus and send the electrical signals back to the spinal cord and brain.

Now the thing is, for the most part, these bundles of axons don't live alone. They are supported by non-neuronal cells called Schwann cells. These cells provide support, maintenance, and nutrition for neurons. Throughout the nerves, the axons are associated with these cells. They can either be wrapped around by myelin sheath produced by these cells or just supported by these cells without any myelin sheath in structures called Remak bundles (see Harty and Monk, 2017).

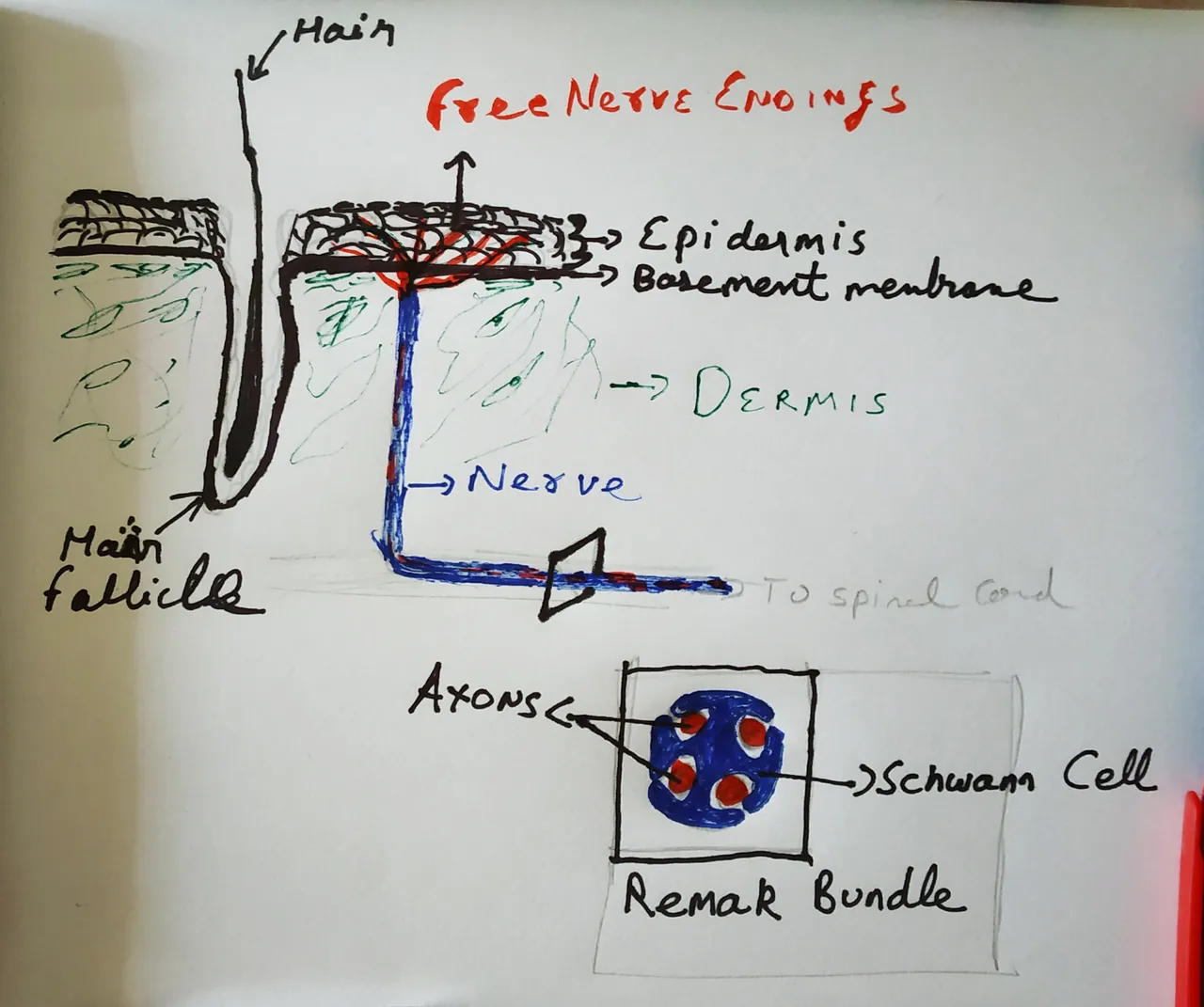

Drawn by @scienceblocks.

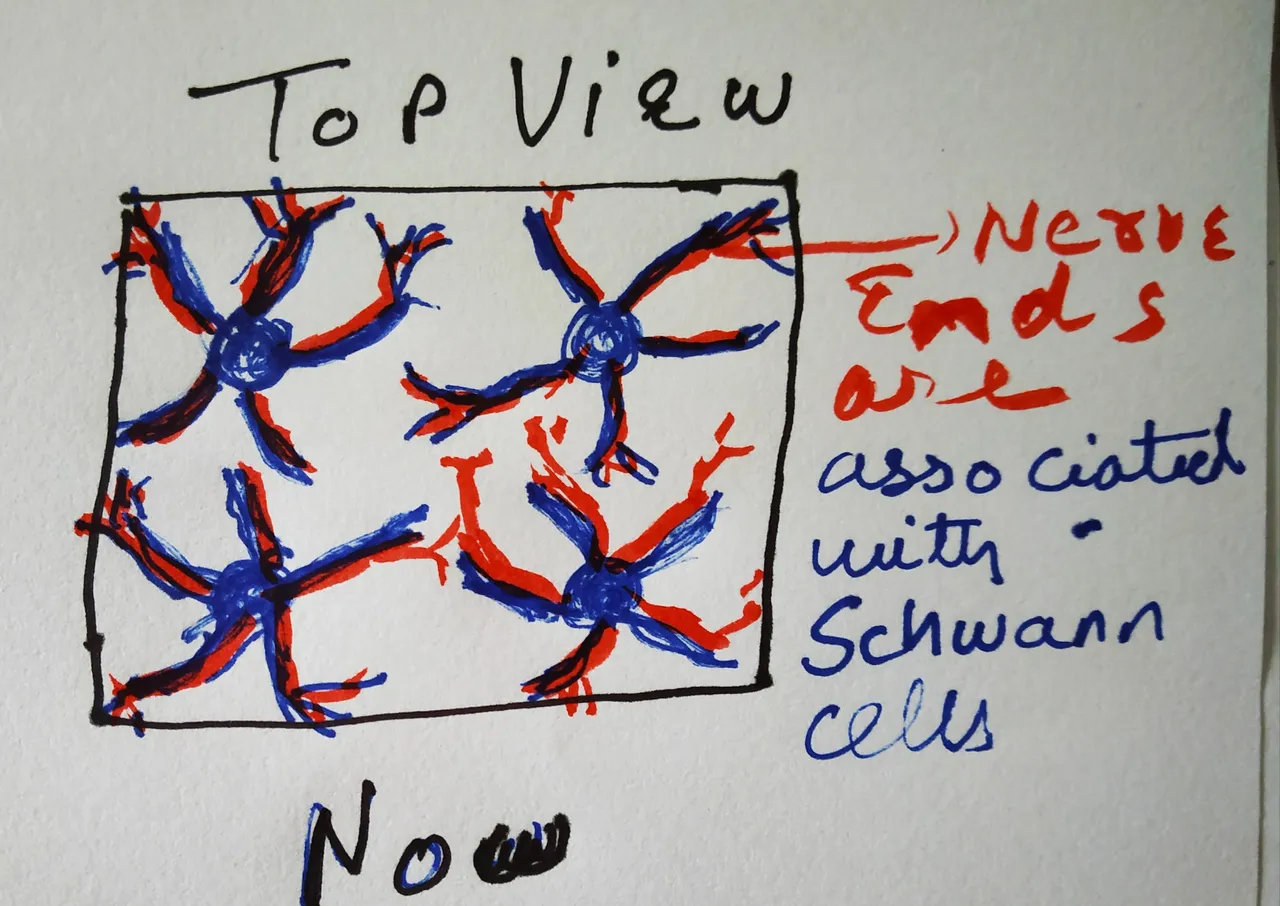

These nerves enter the dermis of the skin. And when it reaches the dermal epidermal-junction, the axonal ends emerge from the nerves and enter the epidermis. Until now we thought that these nerve endings in the skin are naked, irrespective of whether the nerve fibre was itself myelinated or not. And these free, naked nerve endings are what senses the painful stimulus; either directly or by signals from other cells such as keratinocytes in the epidermis (Dubin and Patapoutain, 2010). But, it appears that we were wrong. According to the new study, nerve endings are not naked. They are associated with Schwann cells until the end. In fact, they form a whole mesh-like network of axons and Schwann cells, as if it is a whole organ put out there. Well, the organ part is subjective, but since it is a network of more than one cell types we can call it that.

But, what are Schwann cells doing there? Are they actively involved in sensing pain or they are just there?

What it actually looks like - The story.

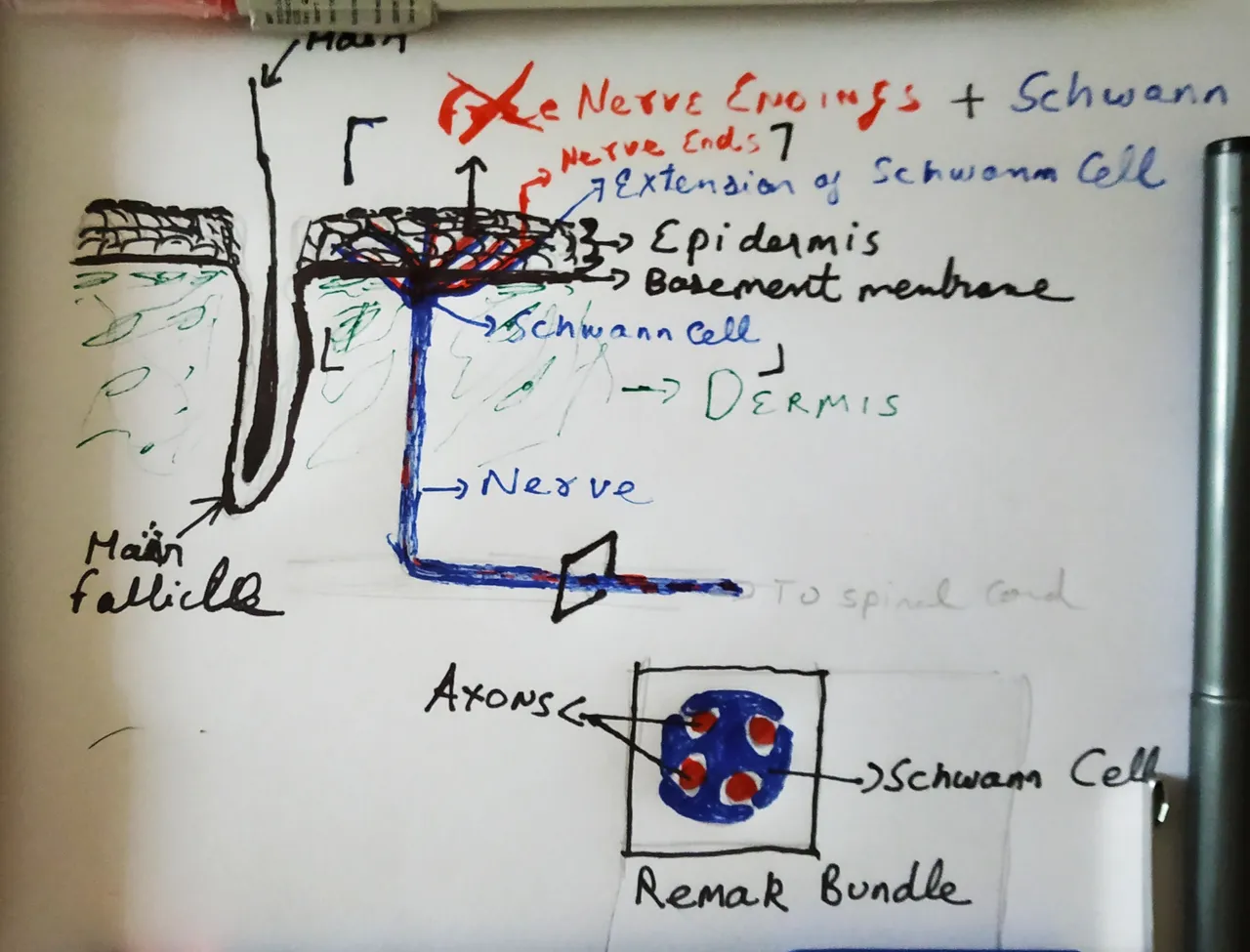

Drawn by @scienceblocks

At the beginning of the study, the authors were looking at how Schwann cells are distributed in the skin. They had different reporter mice - The PLP-YFP mice, Sox10-Tom mice. The PLP, Sox10 are proteins expressed in Schwann cells. YFP is yellow fluorescent protein. And Tom stands for tdTomato - a protein which gives a red fluorescence. Hence, in the PLP-YFP mice, the PLP expressing Schwann cells yellow; in Sox10-Tom mice, the sox10 expressing Schwann cells are red. When the authors stained the skin of these mice with antibodies specific for neurons, they were able to see an entire meshwork of Schwann cells associated with neurons right at the bottom of the dermal-epidermal junction. Moreover, the authors show that the processes of Schwann cells extended into the epidermis along with axonal endings. Therefore, establishing that the nerve endings of the pain-sensing neurons in the skin are after all well dressed.

Vs

How it actually looks like

Drawn by @scienceblocks

Inspired from an image in the paper being discussed

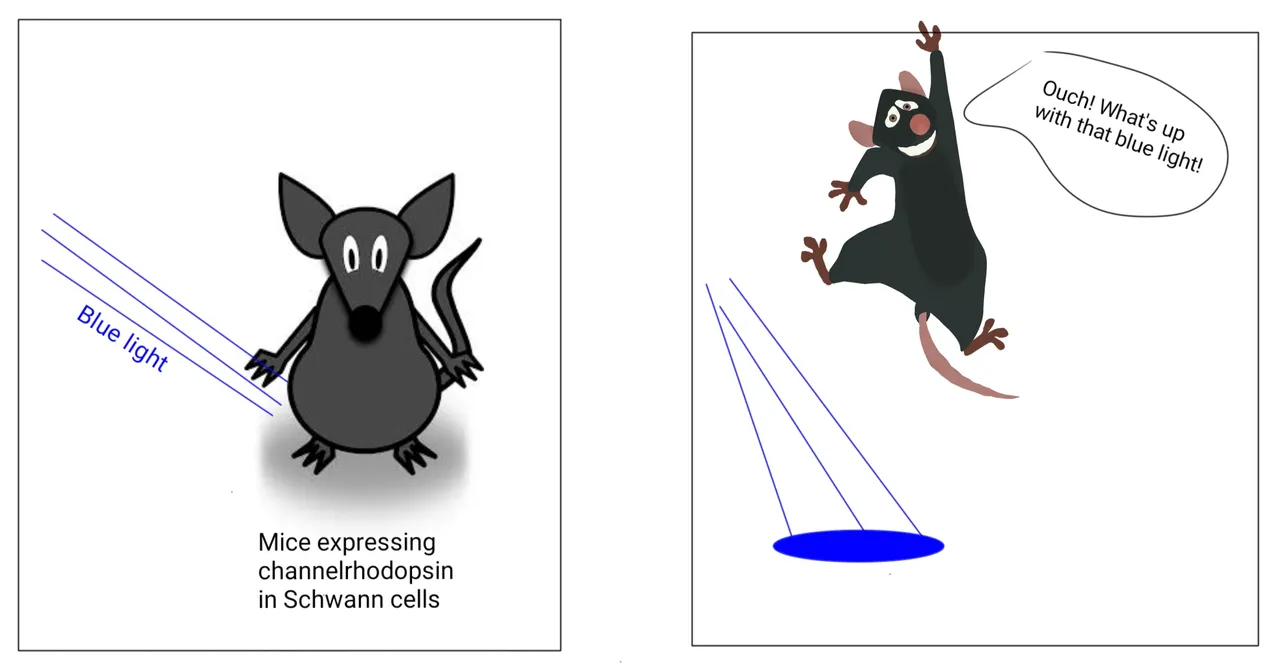

Just activating these Schwann cells with light is sufficient to cause pain.

Illustrated by @scienceblocks using the following images -

Mouse 1 by Clker-Free-Vector-Images.

Jumping mouse by mohamed_hassan.

Pixabay

But do they have an active role to play in sensing pair or were they there just to feed and support the neurons? To test this, the researchers made a few more mice strains. They made the PLP-ChR2 and Sox10-ChR2 mice. ChR2 is a gene for Channelrhodopsin protein. This protein is a light-activated ion channel. So when you shine blue light on it, it lets some ion pass through it. The passage of ion changes the membrane potential of the cell and can activate them. Both, PLP-Chr2 mice and Sox10-Chr2 mice express channelrhodopsin in the Schwann cells they found associated with nerve ending in mice skin.

To their surprise (well in fact even I was surprised reading it), when the activated these Schwann cells with blue light the mice showed the classic signs of pain. They withdrew their limbs as if something has hit them there. Followed by licking, shaking and guarding response. The stronger the power of blue light was used, the stronger was the manifestation of the pain. They also confirmed this by recording the activity of pain-sensing nerves after activating the Schwann cells with blue light. And you bet, these nerves were indeed firing right, left and centre.

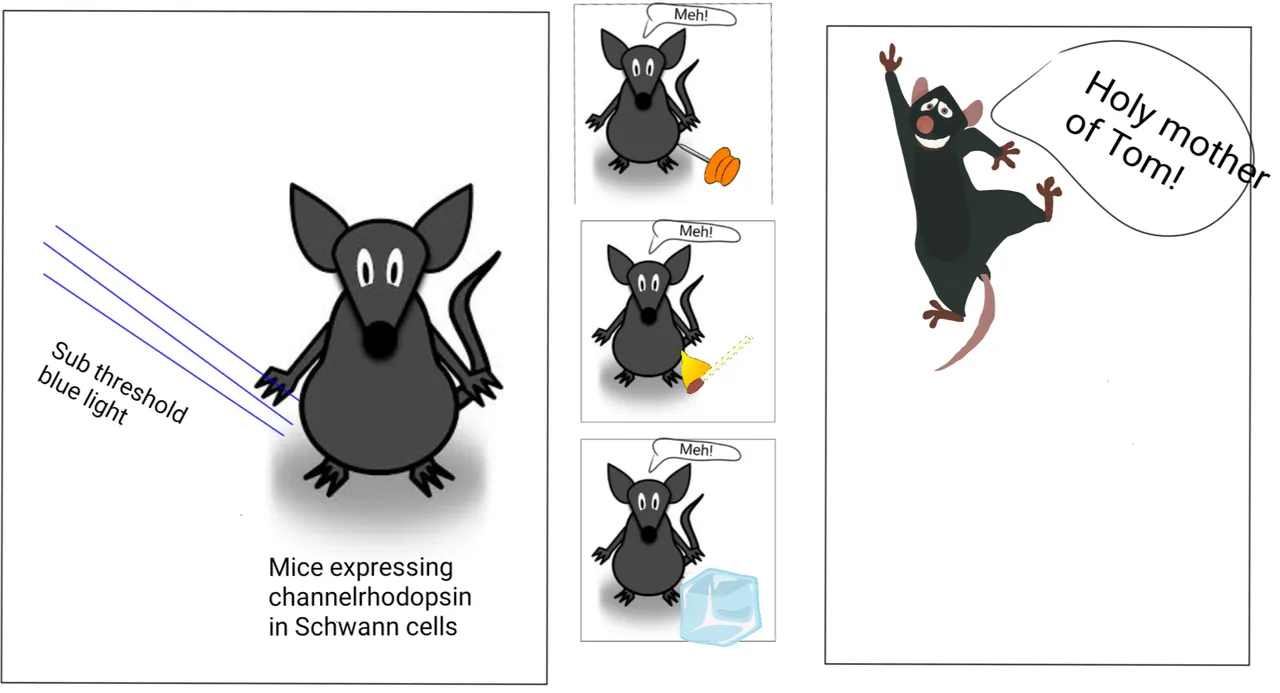

Sensitising the Schwann cell before actual stimulus heightens the pain response.

Illustrated by @scienceblocks using the following images -

Mouse 1, ice cube, matchstick and Pin by Clker-Free-Vector-Images.

Jumping mouse by mohamed_hassan.

Pixabay

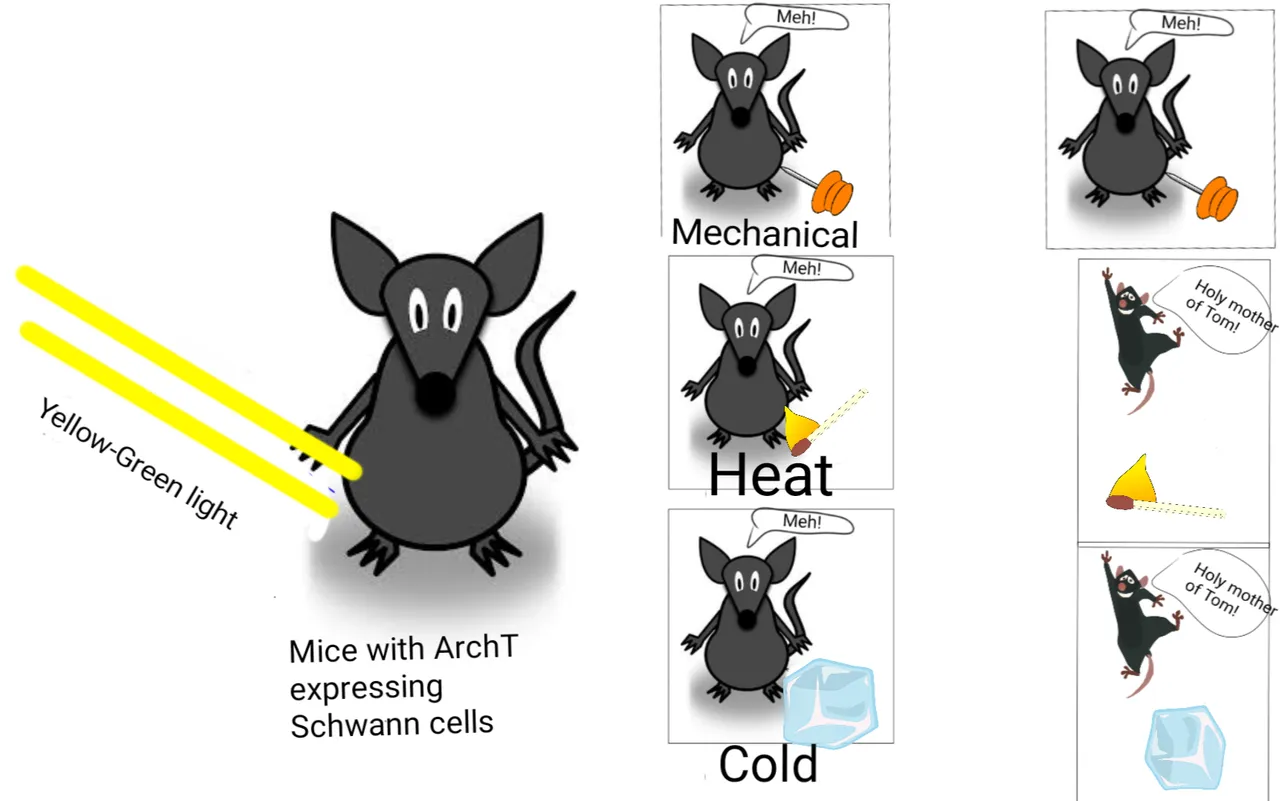

Then came the question about what kind of pain are these Schwann cells are sensing. Pain related to heat? Pain related to cold? Or pain related to mechanical stimulus such as poking or hitting with something? To test this they gave a subthreshold level of blue light, which by itself did not incite pain. But made the mice highly sensitive to mechanical pain, heat and cold. Opps! That did not tear apart anything!

Schwann cells are required for sensing mechanical pain

Illustrated by @scienceblocks using the following images -

Mouse 1, ice cube, matchstick and Pin by Clker-Free-Vector-Images.

Jumping mouse by mohamed_hassan.

Pixabay

So, they made another mouse strain. The sox10-ArchT mice. The ArchT protein is another ion channel that gets activated by yellow light and acts on direction opposite to Chr2. Hence, when yellow light with shine upon the Schwann cells they will get deactivated and should not respond to following painful stimulus. Turns out, that Schwann cells had no role in heat-related pain, but were majorly involved in sensing painful mechanical stimulus.

Schwann cells fire electrical impulses in response to mechanical pressure.

But knowing this isn't enough. All it shows is that pain-sensing nerve endings are associated with Schwann cells. And Schwann cells can somehow directly respond to mechanical pain. I mean alright. But that somehow isn't satisfying enough. What is the mechanism by which the Schwann cells are responding to pain? Can they generate electrical impulses like neurons when mechanical pressure is applied to them?

To test this the researchers went ahead and isolated the Schwann cells from the skin. Grew them in a dish, and performed classical whole-cell electrophysiology on them. The whole-cell recording is the one on which you put one electrode inside the cell and another outside in the buffer solution the cell is bathed in. The two electrodes are connected by a power supply so you can pass the current and record the voltage response of the cell. Using this technique the authors measured the resting membrane potential of the cells. This was followed by measurement of electrical properties of the cells, including the recording of electrical impulses generated by it. Finally, the authors used this tiny micromanipulator tip to put pressure on cell and recorded the electrical impulses generated by the Schwann cells. The Schwann cell fired electrical impulses both when pressure was applied to them or was released. Hence, establishing Schwann cells as mechanotransducers associated with pain-sensing nerve fibres.

Summary and the take-home message

This is for the first time it has been shown that Schwann cells and nerve fibres together form an organ-like meshwork in the skin to sense pain. This opens an entire pandora's box of questions. First being how are electrical impulses being transferred from Schwann cells to nerve fibres? I wish the authors showed if it's by the opening of some voltage-gated channels on a neuron or is there some kind of chemical signalling? Would we find a similar meshwork of Schwann cells in human skin? Quite likely we would. But would have been nice to see how relevant this is to humans. Now Schwann cells have been implicated in many neuropathic pain-related many (see Wei et al., 2019). But, it remains to be seen if unwanted activation of Schwann cells associated with pain-sensing nerves could explain some of the chronic pain associated problems. If so, we should be able to develop strategies to target Schwann cells and make new analgesic drugs.

Oh, this is a fun one I was thinking about. How about a super-soldier who would inactivate Schwann cells before going to one on one combat with an enemy? 😉

Anyhow, that's about it for now. I realise that this paper was a little difficult with those many different genetic strains of mice. I did attempt to explain the jargon I used. But in case I did miss something and you struggled to understand it, do let me know. I will explain further in the comment section. Do let me know if the experiments in this paper were sufficient to convince you that Schwann cells network play an important role in sensing pain. If not what other experiments do you think authors should have done.

A small competition for sbi shares

It's a simple question. The first one to answer any of these questions will get 2 sbi shares.

Why was genetic staining of Schwann cells (that is creating PLP-YFP mice and Sox10-Tom mice) better than just immunostaining with an antibody for sox10 or PLP or some other marker of Schwann cells. What benefit does it provide?

Or

Describe a hypothetical mechanism by which these Schwann cells in the skin could be involved in some chronic pain condition?

About steemstem

But, before I go I would like to mention about the steemstem platform. Well, if you love reading and writing interesting science articles @steemstem is a community on steem that support authors and content creators in the STEM field. If you wish to support steemstem do see the links below.

You can vote for steemstem witness here -Quick link for voting for the SteemSTEM Witness(@stem.witness)

Quick delegation links for @steemstem

50SP | 100SP | 500SP | 1000SP | 5000SP | 10000SP

Delegating to @steemstem gives an ROI of 65% of the curation rewards.

Also, if you have any questions regarding steemstem, do join the steemstem discord server.

You can DM me on discord, I have the same handle - @scienceblocks. Also if you are not a steem user, and reading this blog inspired you to start your science blog, find me on discord and let me know about you. I can try and help you navigate your way through steem.

References

Abdo et al., 2019. Specialized cutaneous Schwann cells initiate pain sensation.

Griffin and Thompson, 2008. Biology and pathology of nonmyelinating Schwann cells

Tao et al., 2009. Erbin regulates NRG1 signaling and myelination

Harry and Monk, 2019. Unwrapping the unappreciated: recent progress in Remak Schwann cell biology