Few years ago (2014 to be precise), I read with interest the story of a South African pastor that told his congregation to eat grass, claiming that doing such will draw them closer to God. Trust the gullible, miracle seeking Homo sapiens ; a lot of the congregation obliged the supposed man of God and the outcome was nothing short of a disaster. The action was greeted by a cacophony of groans caused by stomach pains and vomits. Funny enough, a few of the human-turned ruminants actually claimed various degrees of healings as a result of feeding on the grass. Different strokes for different folks. Perhaps my friend, @zest would have a better version of the story to tell us.

There is no iota of doubts that the earth is blessed with a variety of plants and animals that serve as sources of food for human consumption. The ancestors of man started out with eating raw leaves and fruits in the jungle before the discovery of fire and crude weapons which enabled them to cook their foods and hunt for games for the purpose of meat respectively. One of the arguments of vegetarians is that humans are best adapted to eating plants simply because our ancestors fed on strict plant diets. If such is the case, then we do not also need to cook our meals, we can as well just be feeding on grasses and other plants like ruminant animals.

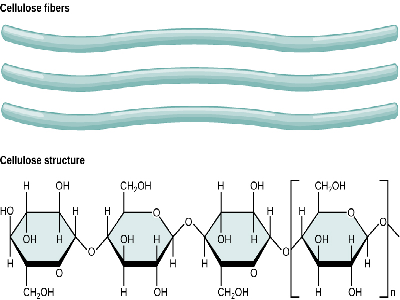

Even though records have it that our ancestors observed plant diets, I am sure grasses were not one of their foods. The plant cell is made up of easily digestible cell contents and somewhat indigestible cell wall made up largely of cellulose and lignin. The cellulose, pectin, gums, mucilage and lignin component make up what is referred to as fibre and in order for digestion to successfully be completed in the human alimentary canal, a certain amount of fibre, known as dietary fibre is needed. While pectin, gum and mucilage portion of the fibre can be broken down during digestion and referred to as soluble fibre, cellulose and lignin are totally undigestable and are otherwise known as insoluble fibre. Soluble fibres function by lowering low-density lipoproteins cholesterol level in the body while the insoluble fibres act by adding bulk to faeces and in doing such, prevents constipation and its associated problems.

Having highlighted the benefits of soluble and insoluble fibre, one begins to wonder why then do grasses constitute problems for humans when it comes to digestion. The answer is not far-fetched. Grasses generally have higher insoluble fibre in form of cellulose and lignin and will be passed out in faeces as consumed, with little or no modification in most cases. The presence of too much insoluble fibre in the diet of humans would lead to different kind of problems ranging from stomach pains to nausea. The amount of insoluble fibre in grasses generally doubles the amount in other plant families.

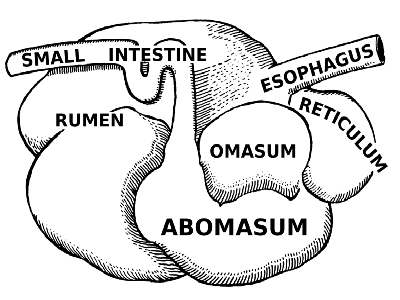

Animals that feed on grasses have a digestive system that is well suited to digesting what would otherwise be an insoluble/indigestible fibre in the human digestive system. These animals are generally referred to as ruminant animals. Instead of a single monogastric stomach that is the characteristic of humans, ruminants have four-chambered stomach lined with microflora of bacteria, protozoans and fungi that help in the digestion of cellulose as well as synthesize essential vitamins for the proper nourishment of the animals. The first stomach chamber which is known as rumen acts as a fermentation chamber for consumed grasses. There, the grasses are mixed with saliva and fermented through the actions of symbiotic microorganisms that produce cellulase enzyme which is necessary for the digestion of cellulose.

The end products of fermentation are carboxylic acids in form of ethanoic, propanoic and butanoic acids as well as carbon dioxide and methane. The acids are utilized as a source of energy during ruminant's respiration. The chemical reactions that accompany the fermentation process generate the energy needed for the metabolic processes of the microbes and creates an ideal environment for them to thrive.

The partially digested grasses which are commonly referred to as cud then move from the rumen to the second stomach chamber, the reticulum, where is formed into pellets. The pellets are regurgitated back into the mouth where it is properly rechewed, a process known as chewing the cud or rumination. The food is thereafter re-swallowed into the third stomach chamber, the omasun where it undergoes further fermentation before moving into the abomasun. The abomasun represent the 4th chamber and functions like the stomach found in humans. From there, the food undergoes the normal digestion process associated with mammalian digestion.

Without the complex digestion procedure associated with the ruminant's digestive system, survival on grass-based diets would have been close to impossible. Generally, grasses have low digestibility due to the presence of lignin which makes up the midrib of their leaves and as such, ruminant animals and their likes have to consume a rather larger quantity of grasses in other meet their body's energy requirement. This generally leads to high faeces turnouts which could be harmful to the environment in the long run.

Therefore, next time your pastor asks you to eat grasses with the aim that it will get you closer to God, you know what's up. Even if such were to be true, it means ruminants are closer to God than humans. Are they?

Thank you all for reading.

References

Convenient Delegation Links: