Economic Growth Through the Eye of the Steamship Industry

Introduction

Extra money seems like a good thing, especially to an aspiring entrepreneur. Starting capital is hard to come by and needed at the early stage of a business. But where should a company get this kickstart funding? They could get it from a venture capitalist, who will spend majority of their time seeing if their money is being used properly. They could get it instead from a fundraiser from many people, who trust that this new product or service will elevate their life. Or they could get it from their government in the form of a subsidy, and in the 1800s of United States’s history, this was the question. Dr. Burt Fulsom gives a presentation of subsidized companies in America versus nonsubsidized, all to answer the question of whether subsidies help an economy grow. Dr. Fulsom makes this as a claim to the modern-day arguments for and against subsidies for companies, with his colorfully presented story of the American steamship companies.

The Economy of the 1800s

To set the stage, Dr. Fulsom lays out why company subsides were such an issue in the 1800s. As the founders of the Constitution planned, the United States was a free country that relied on the ingenuity and work to grow the nation’s economy. However, in the 1800s, this was not good enough. England was a dominant world power that day due to its Industrial Revolution, bringing in factories, trains, and steamships. In comparison, the United States were not growing nearly to that level. English companies had the know-how and material access that American companies had yet to develop. Many an industry went under British domain, until the creation of the steamship. Dr. Fulsom called this creation the “Internet of that Day” to help highlight the impact this innovation had onto transporting goods and information. The steamship cut the travelling time overseas to about half, around 1 to 2 weeks. Unlike with sail boats, steamships were fast and strong enough to push through currents, allowing cuts of cost, time, and inconvenience. At the dawn of steam ships, Edward Collin saw his opportunity to appeal to the U.S. government. Mr. Collin wanted Congress to provide him with a subsidiary of 350 thousand dollars to start a steamship company, with another 3 million dollars to make 4 ships. To why the U.S. government should provide him these funds, Collin explained that American companies needed a kickstart to compete with the English companies. The English companies had a stable, wealthy economy to start their businesses on. The American companies needed subsidies to be on level playing field with these companies. After some deliberation, the Collin Mail Steamship company was made (he made it a mailing company so he could legally get subsides from the government).

Enter Vanderbilt

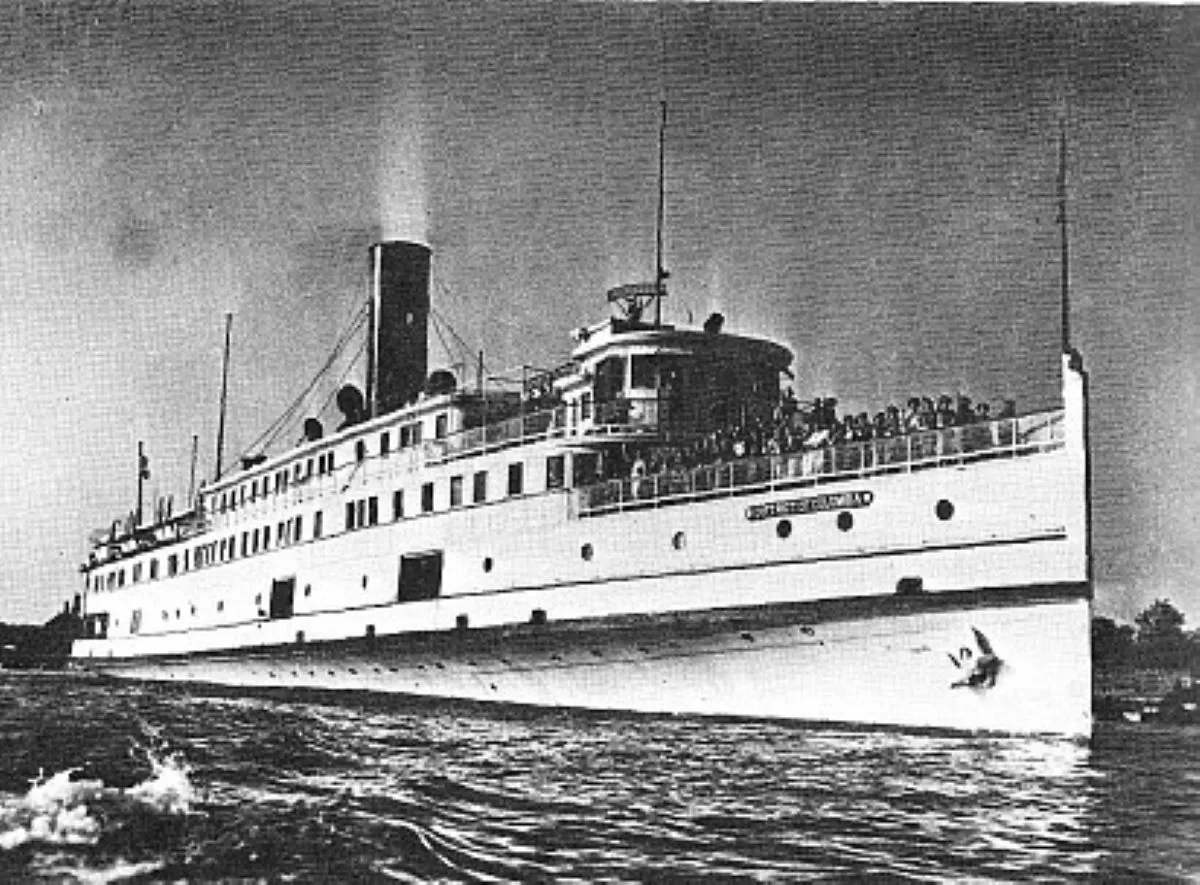

With his company built, he set up his four ships in two locations. Two ships were located in New York City, and two ships were in Liverpool. Collin did not make a profit his first year and came to the U.S. Congress to inquire for a 400 thousand dollars. After he received that money, he came back the next year for a 500-thousand-dollar subsidy. Two years later, Collin was asking for 700 thousand dollars in subsidies. After the years went by of inquiring for money, some men got suspicious of these subsidies. One of these men was Cornelius Vanderbilt. Later nicknamed the “Commodore,” Mr. Vanderbilt decided to inquire Congress for a subsidy of half of what Collin was asking. However, Congress decided to choose Collin, since he had and was running a steam ship company, thus having experience in the field. Vanderbilt was defiant about this decision and decided to run a steam ship company anyway, with no subsidy. With no subsidies, Vanderbilt made his ships go slower, to save full. He also lowered his passenger ticket prices and made a new class: the “sardine class.” As the name suggests, people were packed together. The seats were uncomfortable, but cheap. With all of this saving, Vanderbilt broke a profit in his first year. In comparison, Collin had gone to Congress asking for a 850-thousand-dollar subsidy, in response to the competition from Vanderbilt. After being granted this subsidy, Collin set about marketing his company as the fastest way to travel. However, this resulted in one sunk ship and another one missing. This began the snowball of Collin’s company. He used government funds to build a new ship, which began to take on water in its first voyage. He tried to resell it but only got a $10,000 return on a ship that cost 1 million dollars to make. Finally, Congress pulled his annual subsidiary, and his company went bankrupt soon after. Vanderbilt on the other hand became America’s richest man through steamships and trains.

Conclusion

Dr. Fulsom also described the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, a subsidized project in comparison with James J. Hill’s railroad. The story played out similarly to that of the steamship events of the years before. As can be gathered, nonsubsidized companies perform better both for themselves and for the nation, but why is that. My assumption is that subsidies do not work because the responsibility for the funds has been shifted. In a normal entrepreneurial endeavor, majority of the funds are coming out of my own pocket. I am going to try my hardest to make sure I pay the least as possible. With venture capitalist, they are going to try their hardest to make sure I full the promise of the money they gave me. The responsibility lies with those involved with the development of the company. But with government subsidies, the responsibility for money is not in the development of the company. Some could argue that it’s located in the government, who want to see the company succeed for better national economy, but actually, the responsibility for the capital is not there either. The responsibility lies with the taxpayers. To the company owner, their funds come from the government, so they are not concerned with being efficient with the capital. They feel as if they can mess up more with how the money is used since it is not their own. This same logic applies to the government as well. The government did not make or earn the money they are using to subsidize, so they do not know the value it holds. The value only makes sense to the person who earned it, which is the taxpayer.