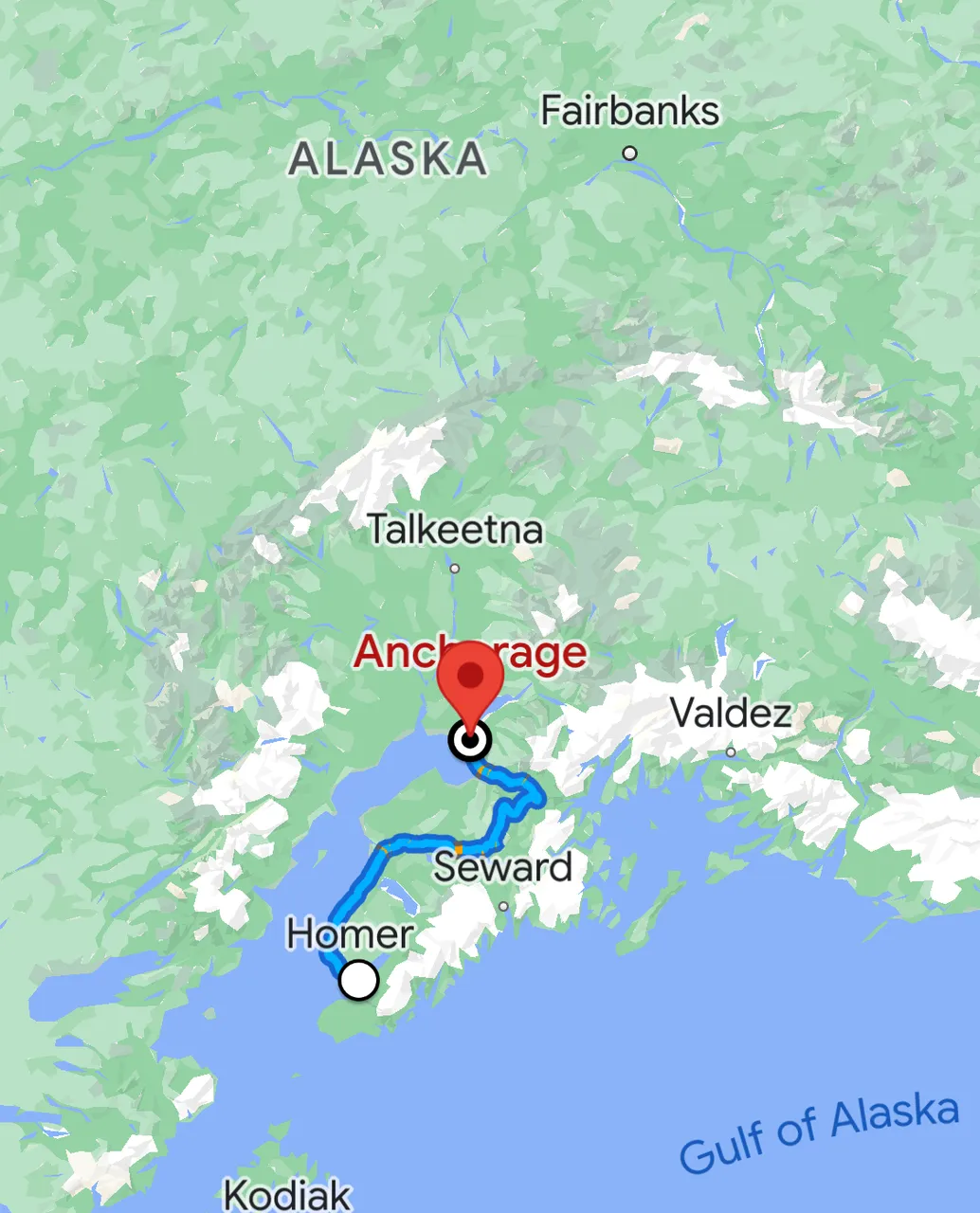

Friday August 12th, 2022. Homer Spit to Anchorage, Alaska.

I wake from a deep sleep, the kind that could have gone on for several more hours were it not for the crow making rattle calls in my campsite. She's a young crow, practicing vocalizations, asking for food. I gaze at her with one eye, my head still half-buried in pillow. I am too tired to rummage for the treats she remembers from yesterday. She gives up after a few minutes. Flies off in search of anything more interesting than a depleted food source.

I get up slowly. Coffee and toilet and such. My soul is damp. Feminine blues and yesterday's rains. It's not raining now. The skies look to be clearing up. Of course they are; I'm leaving today.

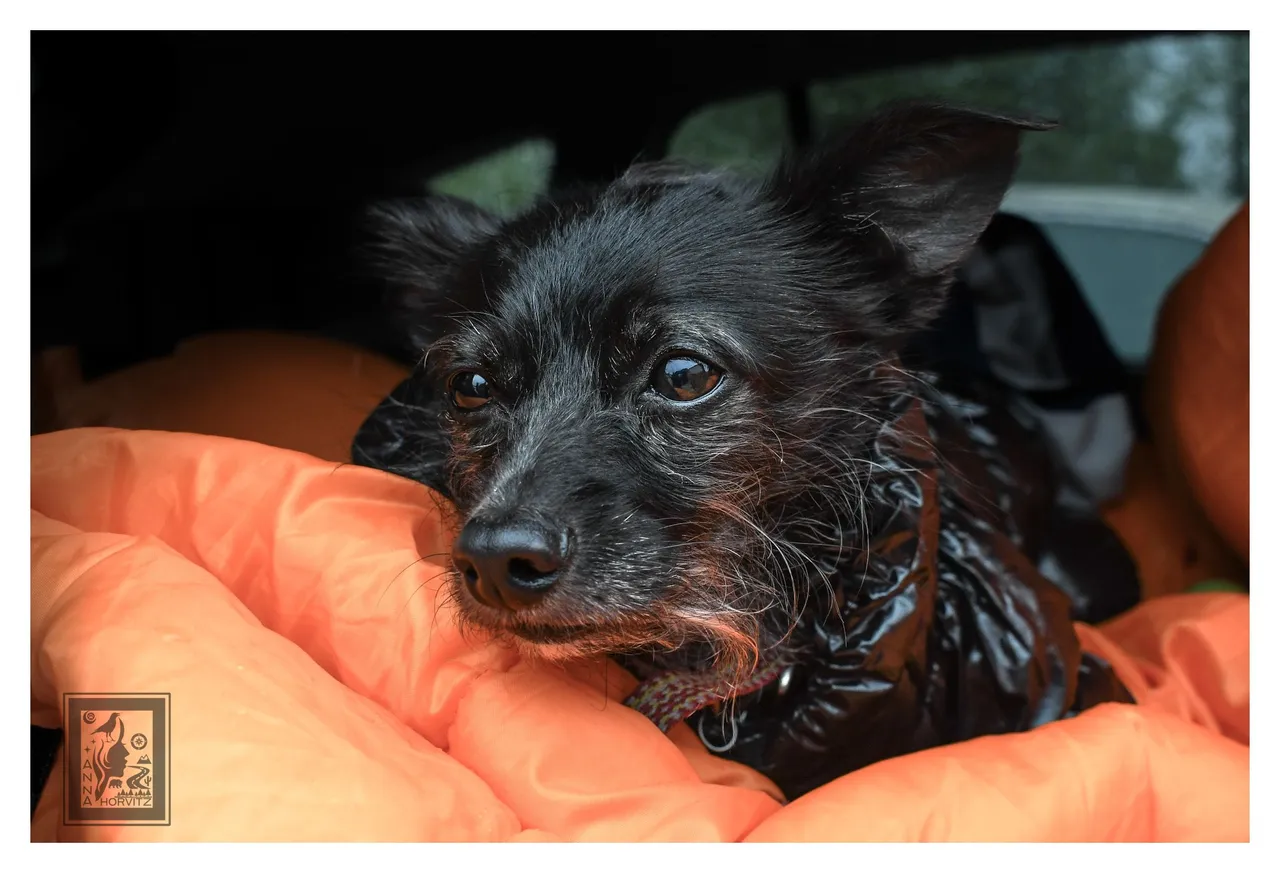

Pilot and I take one last walk on the beach of Homer Spit. I don't know it yet, but it's going to be a hard day. One so full of emotion it will take months before I am ready to reflect and write about it.

Back at the camp site, I watch the motorhome across from me pull out. I wave, not knowing whether or not Gary or anyone else inside sees me. The motorhome bounces and sways out of the campground, and I remember the leftover wine given to me by Gary's friend. It's been sitting out in the rain all night next to my car. I look it over. It's the fruity kind, bottom shelf, probably sugar added. The kind I never drink. I don't want to take it with me, so I offer it to one of my next door camp neighbors. Her eyes light up, and the wine goes to a loving home.

I'm ready to leave, but when I go to start the car it doesn't turn over. Instead I get the familiar click-click-click I heard at the Ranch House Lodge. I must have drained the battery with the dash panel indicator that stayed on all night while the hatch was open.

The battery jumper I bought in Valdez proves ridiculously easy to use, but still the anxiety creeps in. I don't know if I need a new battery. I don't want it to die forever when I'm out in the middle of the arctic. I don't want to buy a new battery if I don't need one, either. I feel like I should know the right thing to do, and I don't.

It tested out good at the shop in Valdez, I reassure myself. If it's dead again tomorrow morning I'll pick up a new one in Anchorage. I try not think about the impact of supply shortages in the state where everything costs twice as much as the lower 48 on a good day. I just hope the damn thing starts and keeps starting from here on out.

The drive takes close to 5 hours. It feels longer. I'm looking forward to seeing my friend Jamie. I want to feel excited, but I can't get my spirits out of the gutter of gloom. It doesn't help that not 30 minutes into my journey a Northern Flicker flies into the side of my car as I am driving. I watch in my sideview mirror as the bird flutters to the ground, then scrambles to escape oncoming traffic. There's nothing I can do, no shoulder on the highway here where I can pull over. There is nothing I could have done to avoid it, either, but knowing this doesn't stop me from fretting over what I could or should have done to prevent or fix it.

A few hours in I stop at a rest area, where I admire a family of swans and their little cygnets. There is something up with them. They act edgy. Nervous, but not the kind of nervous wild birds get when a bunch of sleepy-eyed tourists pull up in their stinky bird-slaughtering cars to point and photograph. They are shaken.

I look out across the water to the opposite bank. My eyes fall upon a familiar shape. I use my 600mm lens as a telescope and zoom in on the white dot.

An eagle. Bald eagle. Sitting in the grass like that he is probably eating. Eating what? A cygnet?

No police report. No forensics. No funeral. The swan family has no choice but to keep living their everyday life. But with the eagle eating, they are safe for now.

The greeting I receive from Jamie and her daughter Emily is warm when I get into Anchorage. It lifts my spirits enough to pull me out of my rain-drenched, menses-induced funk. I don't talk about the bird that hit my car or complain too much about the rain. It's good to see Jamie, especially after all this time. Our friendship in Portland had been a jolly one until she bought the grooming shop where I worked and became my boss for two years. It put a strain on our friendship and my loyalties to other friends that worked under her, and the good times fizzled out. But that is years behind us, now.

We go for a hike around a nearby lake. Jamie carries bear spray, and Emily talks to me about the ducks and the wildlife and her school, which teaches her about the value of our place in nature and hosts winter picnics in the snow. She's a little wood sprite, this one. Orange buttercream hair and bright blue eyes. She calls me Annabanana. One word. It's my name, now, here in Anchorage.

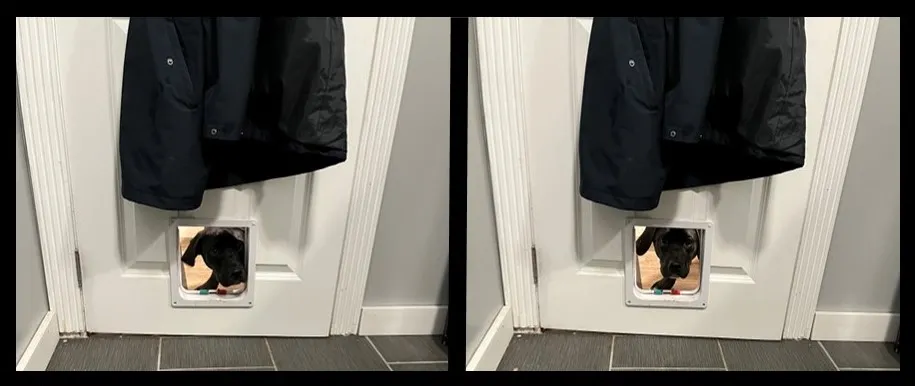

We're going out to dinner tonight. Emily is still in her pajamas and I am still wearing the same clothes from yesterday, so we stop back at the house to get changed and let their dogs out. There are two of them. Big dogs. One, grumpy old Maple, I remember from Portland. The other is a young pup Jamie unwillingly acquired from her brother, whose life has been falling apart at the seams for the last umpteen years.

Jamie goes out back to let the dogs out and have a cigarette. I come outside to chat while Emily plays around in her room and pretends to get ready. Jamie shows me the yard. I let Pilot sniff around. They have chickens, a garden, a big beautiful deck. Homes are cheap up here. You can get a house with a yard in Anchorage for less than what it costs to rent a one-bedroom apartment in Portland. My head swims with runaway fantasies.

The pleasantness of my reveries is shattered when Maple starts growling at Pilot. Pilot is a good dog, very polite and conflict-avoidant, but Old Maple has stiff-leggedly pushed him into a corner. If he moves, she'll pounce. I approach with a gentle voice. Lean in to pick Pilot up. In a flash of fur, Maple is on top of him. Growling. Slobbering. Pilot is screaming. Maple is six times his size, at least. She could kill him if she wanted to.

Carnal, guttural, and probably blood-curdling sounds involuntarily pour out of me. I grab Maple. Without knowing what I am doing, I take hold of her collar and scruff and lift her seventy-pound plus body halfway into the air. I see Pilot shoot out from under her. I yell at him to run. He looks at me. Looks into my eyes. A fraction of a second held eternal in my memory. Then he takes off under the deck.

Jamie is there in a flash. She gets hold of Maple and takes her into the house while I look for Pilot. He's under the deck, searching for a way to get out of the yard completely. I call him. Beg him to come back. He is terrified. I am terrified. I don't want him to slip under the fence and start running down the streets of Anchorage.

"Pilot, come here, please," I say with urgency and as much love and confidence I can muster over the adrenaline coursing through my body. "Come here, buddy. I got this guy, ok? I got this guy."

I got this guy. It's something I say to him when he's unsure of a situation. Usually it involves me picking him up and comforting him or helping him through a precarious situation. A scary noise, or puddle or stream too big to jump over. I'm a fucking liar, though, because I don't got this guy. I just let this guy get mauled by a giant bear of a dog when I never should have left him alone with her. But my tone is convincing, and, thankfully, Pilot creeps toward me.

"I got this guy," I say again. I reach out and slip my fingers around his collar. He screams. But he lets me pull him into my lap. I wrap my arms around him. He keeps screaming.

"I got this guy." At last we are safe, and my body begins to shake. Searing tears boil over my lids and roll down my cheeks. "I got this guy." I rock back and forth. Hold on to him until he is goes quiet.

"I got this guy."

Maple is a bitch but thankfully not a killer. Her tremendous and terrifying scene leaves Pilot with little more than a slathering of slobber and a lasting impression. I palpate his entire body. No blood, no wincing, no screams. She didn't hurt him.

We leave for the steakhouse in separate cars. Pilot rides with me so he can wait in the carbed and its familiar stink. After dinner I bring him a shrimp and a large chunk of steak, which he eats with a wide-eyed smile.

Back at Jamie's place, Emily disappears to play videogames in her bedroom while dressed in a unicorn onesie, and Jamie and I slip out back to chat about grownup things. Back in the day a gathering like this would have called for some serious drinking, probably wine or cocktails, but I'm not much of a drinker anymore, and she's home alone with her daughter while her husband is working an engineering contract gig in Arizona. So we drink tea. Talk about the good and the bad in our lives. She's worn out from taking care of her substance-abusing sibling. Tired of giving him support he says he wants but doesn't use. She feels like the last person in the family who cares about him. We have some parallels in our childhoods, Jamie and I. Things that were missing that should have been there for us kids. We swap memories.

"You look down when you talk about it, Anna," Jamie says to me. She's right. I'm staring at the floorboards of the deck after recounting some dysfunctional worldview I'd grown up with. In a flash I am embarrassed, yet at the same time wonder why I should feel so ashamed when I talk about my childhood. Why I still feel ashamed over incidents that were entirely out of the control of an innocent little kid.

Shame. I've lived with it for so long. Let it make too many decisions. Let it keep me invisible. Shame made me believe every mistake, every imperfection, would ultimately lead to more suffering. Shame made me downplay each accomplishment and examine more closely where I had failed rather than what I had done.

Shame has tried to hold me back but here I am, HERE I AM, in FUCKING ALASKA, living out a lifelong dream. Why do I still hold onto shame?

All pictures and words copyright Anna Horvitz (me) and cannot be used without my consent.